This story was originally published by Fusion and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Environmentalists rejoiced last summer when Barack Obama and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, fresh at the start of their very public bromance, announced their cooperation on climate change. After nine years of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who cut research funding and pulled Canada out of the Kyoto Protocol, it seemed Canada was finally getting back on track when it came to environmental policymaking, while Obama was continuing his second-term push to address climate change.

Now, nearly a year later, it’s clear that Donald Trump will not be carrying on Obama’s environmental legacy. But where do Trump’s policies — which include dismantling the Clean Power Plan, broadly cutting the EPA, and potentially pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Climate Agreement — leave Canada?

“The timing is so terrible because we finally have a prime minister who wants to do something about the environment matched with a president who doesn’t,” said Andrea Olive, an assistant professor in geography and political science at the University of Toronto. “It’s like we switched sides. And now the environment is not going to improve — one team can’t pull all the weight.”

Bordering on climate change action

For Canada, the biggest environmental policy concern surrounding the Trump presidency is his action — or inaction — on climate change, Olive said. Specifically, Trump backing out of the Paris Agreement would be “devastating” — a sentiment echoed by Erin Flanagan, director of the federal policy program at the Calgary-based Pembina Institute.

“I hope it’s not true, because the Paris Agreement is just so important to the world, and is just a groundbreaking agreement,” she said. “I think it’s really quite bad from a symbolic perspective to have the U.S. remove itself from those conversations.”

But rest assured: No matter what Trump does, Canada will maintain its position in the Paris Agreement. “The government has been quite clear on that,” Flanagan said. Whether or not the Canadian government will succeed in meeting its goals under the Paris Agreement, which aim to cut emissions 30 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, while still approving tar sands pipelines, is another question. In some ways, Trudeau is an about-face environmentally from Prime Minister Harper: He’s repeatedly stated that climate change is happening, and his government is working to implement climate policies, including a price on carbon. But environmentalists like Bill McKibben point out that because Trudeau is still set on developing Canada’s tar sands and building pipelines to get that high-carbon resources to market, his climate policies will do little to actually address climate change.

But there is at least little worry that Trudeau will back out of the Paris Agreement — an action that would echo Prime Minister Harper’s choice to back out of the Kyoto Protocol, citing the United States’ and China’s non-involvement in the treaty.

Trump’s inaction on climate may make Canada’s implementation of the agreement tricky, however.

“Our economies are so integrated that it’s impossible to think that we could implement the Paris protocol if the United States is not doing it,” Olive said.

In terms of vehicles, for instance, Canada might be less likely to implement more stringent emissions standards as a step toward meeting Paris targets if America isn’t increasing its emission standards. In fact, emission standards are among the issues that are most worrisome about a Trump presidency, said Flanagan. Canada and the U.S. have highly integrated vehicle economies, with vehicle parts being made on both sides of the border. Because of this integration, the two countries have cooperated since 2010 on increasing fuel efficiency standards, with a goal of 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. Trump, however, announced in March his EPA would be reviewing Obama-era standards.

“Anything that the Trump administration does to go backward on those makes it harder for the U.S. to hit its climate targets,” Flanagan said. “And then it causes a question mark for Canada, so that Canada has to decide: Do we follow that direction of essentially allowing cars to pollute more than they otherwise would, or do we go in another direction?”

Though Trump’s move has created some uncertainty in Canada, Flanagan said the Trudeau government “would be hard pressed” to roll back emissions standards, considering his stated commitment to addressing climate change.

Another climate-related concern, Flanagan said, is methane. The potent greenhouse gas is emitted largely by oil and gas operations, and last year, the U.S. and Canada committed to cut methane production by 45 percent from their oil and gas sectors. This was a win for environmentalists, but also made things simpler for the oil and gas industry, she said. The U.S. rule aimed at reducing methane at new oil and gas wells is another one that Trump has ordered the EPA to review, while Canada’s new rules on methane emissions from the oil and gas sector, which will continue on the reduction path, should be coming out in the next few months, Flanagan said. Now, however, it’s likely that oil and gas companies will have to adhere to different standards depending on which side of the border they’re on.

The Canadian government is also considering a request from British Columbia Premier Christy Clark to halt shipments of U.S. coal from Canada’s West Coast. This request came as a response to Trump imposing duties on imports of Canadian softwood lumber, and delivers a setback to Trump’s promises of ending the “war on coal.”

Cutting environmental budgets

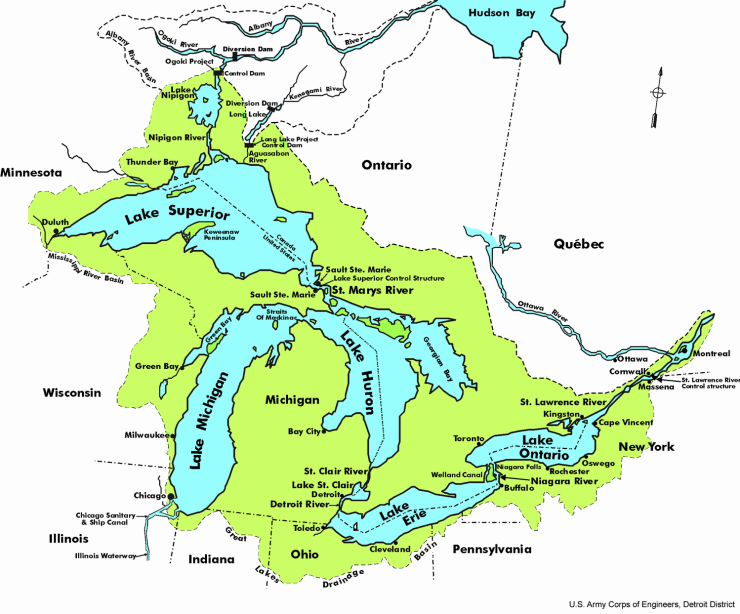

Earlier this month, the U.S. Congress passed a budget deal to keep the government open through the end of September. That deal did not include proposed cuts to the EPA. However, the agency isn’t out of the woods yet: Trump’s proposed 2018 budget, which came out in March and will be voted on later this year, eliminates funding for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. That $300 million program works to restore wetlands, clean up pollutants, combat invasive species and reduce runoff into the lakes, which hold 84 percent of the surface freshwater in North America and are home to more than 170 species of fish. Since 1972, the U.S. and Canada have cooperated to keep the Great Lakes clean under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

The relationship between Canada and the U.S. is a “very meaningful one,” Olive said. It’s got roots stretching back to 1909, when the U.S. and Canada, then under British rule, signed the Boundary Waters Treaty.

The Great Lakes watershed. Wikimedia Commons

“It’s almost like a slap in the face to Canada to defund that,” she said. “The rockbed of our bilateral environmental relationship is this concern for the Great Lakes.”

The Great Lakes aren’t just a source of water or recreation for the people who live around them, she said; they’re hugely important culturally.

“For people who live in the Great Lakes, the Great Lakes are very much a part of their identity,” she said. “For the United States to defund that … it’s almost offensive.”

If the program is defunded, Olive hopes some slack will be picked up by the states.

“I do think it’s going to affect the physical environment — I am worried about water quality issues, things around algae blooms, things around endangered species,” she said. “But there’s still the potential that the U.S. states are going to get more involved.”

The proposal to eliminate funding for the Great Lakes has drawn the ire of U.S. lawmakers — both Democrat and Republican.

“The idea that the administration would eliminate a program that protects drinking water for more than 30 million people is hard to comprehend,” Republican Ohio representative Dave Joyce said in March.

Canadian Environment Minister Catherine McKenna said in March that Canada “invests significant resources in restoring and protecting the Great Lakes” and that it would continue with its “commitment to keep protecting this precious resource.”

It’s almost like a cultural war

What might be most troubling about Trump for Canadians — especially Canadian environmentalists — isn’t one particular action, however; it’s his overall disdain for the environment.

“He’s just looking to destroy everything,” said Inger Weibust, assistant professor of international affairs at Ottawa’s Carleton University. “It’s almost like a cultural war, an all-out war on the kinds of things that certainly environmentalists hold dear.”

Olive agrees.

“He’s made it OK to be pro-coal; he’s made it OK to be anti-climate; he appointed somebody to head the EPA who thinks climate change is a hoax — he’s made this attitude OK. I think that’s deeply troubling,” she said.

But in terms of Canadian action on climate and the environment, Canada’s priorities aren’t likely to change much because of a Trump presidency. The provinces that are interested in tackling environmental issues and climate change will carry on that path, Olive said, and the provinces that don’t want to do anything will use America’s inaction as another excuse not to. And it doesn’t appear much has changed in terms of federal action either.

“When Trump was elected, and Canada was in the process of developing their climate plans, there were a lot of questions — was this a good time to bring in federal climate policies?” Flanagan said. “At the end of the day, the federal government but also many of the provinces decided yes, despite the uncertainty in the U.S., Canada needs to do this.”

Canada, she said “is catching up on climate change in many ways.” The country hasn’t historically been a leader in climate action, but now, under the Trudeau government, it’s slowly starting to move forward in environmental policy — in spite of its continued support of the tar sands — and will likely continue to do so regardless of what Trump does.