Look, at this point, even the most stubborn among us know that climate change is coming for our asses. We really don’t have much time until the climate plagues we’re already getting previews of — mega-wildfires, rising sea-levels, superstorm after superstorm — start increasing in frequency. The 4th National Climate Assessment says all that and much more is on its way.

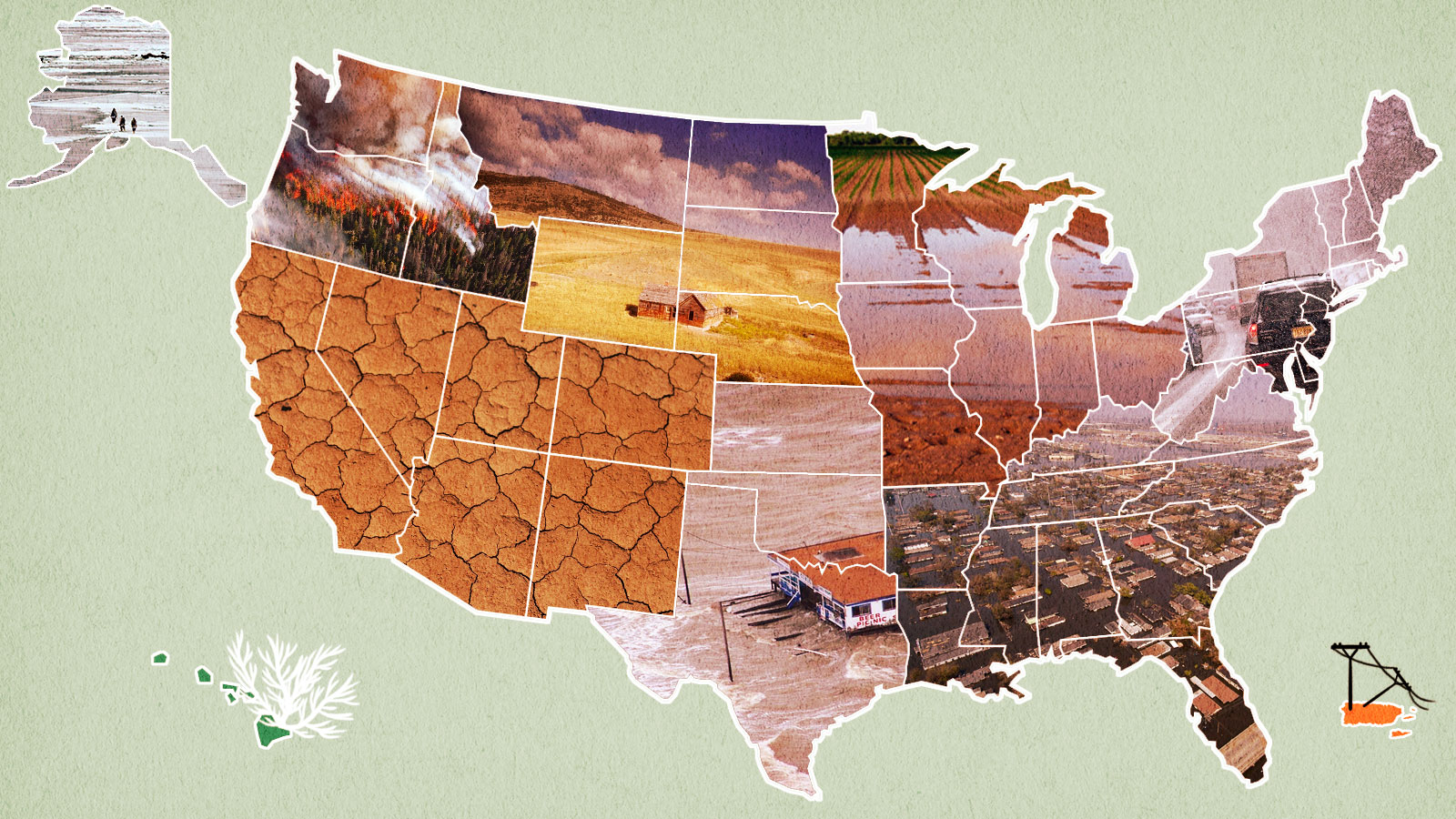

Here’s the thing: Not all regions in the U.S. are going to experience climate change in the same way. Your backyard might suffer different climate consequences than my backyard. And, let’s be honest, we need to know what’s happening in our respective spaces so we can be prepared. I’m not saying it’s time to start prepping your bunker, but I would like to know if my family should consider moving to higher ground or stock up on maple syrup.

Luckily, that new report — which Trump tried to bury on Black Friday — breaks down climate change’s likely impacts on 10 specific regions. Unluckily, the chapters are super dense.

Silver lining: We at Grist divvied up the chapters and translated them into news you can actually use.

Northeast

Ahh, the Northeast, home to beautiful autumn leaves, delicious maple syrup, and copious amounts of ticks bearing disease. What’s not to love? A lot, according to this report.

Our region is looking at “the largest temperature increase in the contiguous United States” — 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit by the time 2035 rolls around. We’re going to be slammed with the highest rates of sea-level rise in the whole damn country, and we’re going to have the highest rate of ocean warming. Urban centers are particularly at risk (remember Superstorm Sandy?). And if you’re a fan of snuggling up beside the fire in your Connecticut mansion (or whatever), be warned that winters are projected to warm in our region three times faster than summers. That means delayed ski seasons and less time to tap maple trees.

Things are gonna be rough on us humans, but dragonflies and damselflies — two insects literally no one ever thinks about, but that flourish in healthy ecosystems — are pretty much doomed. The report says their habitat could decline by as much as 99 percent by 2080.

Sea-level rise, flooding, and extreme weather poses a mental health threat to Northeasterners. Impacted coastal communities can expect things like “anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.” But it’s not all bad: The assessment portends more intense (read: Instagram-able) fall foliage and more forest growth.

Southeast

If, like me, you love your filthy, dirty South, you’ll be pleased to hear that summer thunderstorms, skeeters, ticks, and hot, muggy weather aren’t going anywhere! (Actually, don’t be pleased. This is serious.)

Southerners are accustomed to warm days followed by warm nights, but as the heat continues to turn up, those nights just might be our downfall. Urban and rural areas alike can expect to sweat through up to 100 additional warm nights per year by the end of this century. Hot, sticky nights make it harder for us to recover from the heat of the day. This is especially bad in parts of many Southeastern cities, where residents suffer from the “heat island effect.”

“I think it’s really important to look at the heat-related impacts on labor productivity,” says chapter author Kirstin Dow, a social environmental geographer at the University of South Carolina. Under one scenario, the Southeast could see losses of 570 million labor hours, amounting to about $47 billion per year — one-third of the nation’s total loss. What’s more, Dow says, “Those changes are going to take place in counties where there’s already chronic poverty.”

Warming waters will also push the infamous lionfish closer to the Atlantic Coast. In addition to being invasive, this freaky-looking fish is venomous, and swimmers and divers can expect more encounters (and stings) as the climate brings them closer to our beaches.

Caribbean

For someone who doesn’t like donning heavy clothing during the winter, the Caribbean has the perfect weather: year-round warm days with ocean breezes. Climate change, according to the report, means we can’t have nice things.

In the near future, the Caribbean will experience longer dry seasons and shorter, but wetter rainy seasons. To make matters worse: During those arid periods, freshwater supplies will be lacking for islanders. And since islands (by definition) aren’t attached to any other land masses, “you can’t just pipe in water,” says Adam Terando, USGS Research Ecologist and chapter author.

The report confirmed something island-dwellers know all too well: Climate change is not coming to the Caribbean — it’s already there. And it’ll only get worse. Disastrous storms the likes of Hurricane Maria — which took the lives of nearly 3,000 Puerto Ricans — are expected to become more common in a warming world.

Another striking result: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are projected to lose 3.6 percent and 4.6 percent of total coastal land area, respectively, posing a threat to critical infrastructure near its shores. The tourism industry will have to grapple with the disappearance of its beaches. Even notable cultural sites aren’t safe: Encroaching seas threaten El Morro — a hulking fortress that sits majestically on the coast of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“Our island is trying to limit its emissions — but we’re not big emitters,” lead chapter author Ernesto L. Diaz, a coastal management expert at Puerto Rico’s Dept. of Natural and Environmental Resources, tells Grist.

Midwest

What’s in store for the Midwest? Oh hello there, crop diseases and pests! Hold onto your corn husks, because maize yields will be down 5 to 25 percent across the region by midcentury, mostly due to hot temps. And soybean hauls will decline more than 25 percent in the southern Midwest.

Beyond wilting crops, extreme heat puts lives at risk. The Midwest may see the biggest increase in temperature-related deaths compared to other regions, putting everyone from farmworkers to city-dwellers at risk. In one particularly bad climate change scenario, late-21st-century Chicago could end up seeing 60 days per year above 100 degrees F — similar to present-day Las Vegas or Phoenix.

The Great Lakes represent 20 percent of freshwater on the world’s surface, but lately, they’re looking … not so fresh. Climate change and pollution from farms are leading to toxic algae blooms and literally starving the water of oxygen.

But hey, there’s a silver lining. Midwesterners (myself included) have developed a bad habit of leaving their homeland for other parts of the country. That trend may reverse. “The Midwest may actually experience migration into the region because of climate change,” Maria Carmen Lemos, a Midwest chapter author and professor at the University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability, said in a statement. So while you may have to reconsider your ice-fishing plans, Midwesterners, it could be a whole lot worse.

Northern Great Plains

The Northern Great Plains is far from any ocean. Water melts off mountain snowpack, slowly trickles down glaciers, and pools up in basins. The largely arid region is dominated by thirsty industries like agriculture, energy extraction, and tourism. There’s a byzantine system of century-old water rights and competing interests.

Or as my dad, a Montana cattle rancher, puts it: “Whiskey is for drinking. Water is for fighting.”

Residents might want to steel themselves with a little bourbon as climate change will escalate those water woes, according to the report. Winters will end earlier and snow could decline as much as 25 to 40 percent in the mountainous regions.

It’s not just some far-off problem for cross-country skiers and thirsty critters. The authors point to the behavior of the mountain pine beetle as one example of a climate-influenced tweak that’s had devastating impact. Warmer winters and less precipitation have enabled the bugs to kill off huge swaths of forest in the region.

Lest you think what happens in the Dakotas stays in the Dakotas: While only 1.5 percent of the U.S. population lives in this region, it contributes nearly 13 percent of the country’s agricultural market value.

It’s culturally critical, too: The area is home to 27 federally recognized tribes that are already experiencing climate threats such as a lack of access to safe water and declining fisheries.

Southern Great Plains

The Southern Great Plains flips between heat waves, tornadoes, drought, ice storms, hurricanes, and hail. The weather is “dramatic and consequential” according to the report. It’s “a terrible place to be a hot tar roofer,” according to me, a former Kansas roofer. In a warmed world, none of this improves. Well, maybe the ice storms.

The region will continue to have longer and hotter summers, meaning more drought. Portions of the already shrinking Ogallala Aquifer, which is critical to a huge western swath of the region, could be completely depleted within 25 years, according to the report.

Texas’ Gulf Coast will face sea-level rise, stronger hurricanes, and an expanded range of tropical, mosquito-borne diseases like dengue and Zika. It’ll also experience more intense floods. Many of the region’s dams and levees are in need of repair and aren’t equipped for the inundations.

One of the chapter’s lead authors, Bill Bartush, a conservation coordinator with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, tells Grist that how landowners handle the extremes of water management will be key to climate adaptation. Given the region’s high rates of private land ownership, it’s essential to get them on board.

In weirder news, the region’s Southern Flounder population is declining because the fish’s sex is determined by water temperature. Warmer winters mean more males. It’s like a terrible reboot of Three Men and a Baby, but with more flounder and no baby.

Northwest

The Pacific Northwest has more rain in its winter forecast. That might not sound unusual for a region known for its wet weather, but more winter rain — as opposed to snow — could impact the region’s water supply and entire way of life.

Most of the Northwest relies on melting mountain snow for water during the summer. Climate change will replace more of that snow with rain, which flows downstream right away rather than being stored on mountainsides until the temperatures warm. Less snowmelt during hot summers could damage salmon habitat, dry out farms, harm the region’s outdoor industry, and increase wildfire risk.

“It’s like our tap is on all the time,” said Heidi Roop, a research scientist at the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group, which helped author the chapter.

The report forecasts a lot of change in the Northwest, including flooding and landslides. But rainy winters? That’s one thing that’s not going away anytime soon.

Southwest

“I am large. I contain multitudes,” Walt Whitman said of himself. But he could have very well said it of the Southwest, where stretches of desert give way to soaring, snow-capped mountains. Yet this might not be the case for long. Climate change threatens all of this beautiful ecological diversity, as well as the 60 million people who call this area home, including 182 tribal nations.

The hottest and driest corner of the country is already suffering from heat waves, droughts, and increased wildfires. As a result, the Southwest, to put it bluntly, is running out of water. With water at already record low levels and a population that continues to grow, the region is working on a recipe for water scarcity.

“Lake Mead, which provides drinking water to Las Vegas and water for agriculture in the region, has fallen to its lowest level since the filling of the reservoir in 1936 and lost 60 percent of its volume,” coordinating chapter author Patrick Gonzalez, a climate scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, tells Grist.

In the coming years, temperatures in this region will soar. Droughts, including megadroughts lasting 10 years, will become commonplace. Agriculture will take a steep hit, causing food insecurity. Expect those lovely desert sunsets to take on an unsettling pink, as the snow-capped mountains grow bald.

Alaska

In Alaska, water is life, life is shellfish, shellfish is power. But, alas, climate change is about to do a number on the state’s marine life, food webs, and species distributions. According to the climate assessment, ocean acidification is expected to disrupt “corals, crustaceans, crabs, mollusks,” as well as “Tanner and red king crab and pink salmon.” Lots of indigenous peoples rely on that variety of marine life.

The largest state in the country is already ground zero for climate change. Thawing permafrost means structures are literally sinking into the ground all over the state.

What does a temperature increase really mean? Well, under the worst-case scenario, the coldest nights of the year are projected to warm 12 DEGREES F by midcentury.

I know I said water, either frozen or liquid, is the name of the game in Alaska, but the report says the state should expect more wildfires in the future, too. Under a high-temperature-increase scenario, as much as 120 million acres could burn between 2006 and 2100. That’s an area larger than California.

Oh yeah, and the report says there’s going to be an increase in “venomous insects.” Cheers.

Hawaii and the Pacific Islands

This region houses 1.9 million people, 20 indigenous languages, countless endemic (one-of-a-kind) flora and fauna species, and the freaking Mariana Trench (the world’s deepest point).

Pacific island communities can expect to grapple with the usual climate change suspects: rising sea levels, weird rainfall patterns, drought, flooding, and extreme temperatures. But all those things have unique implications for supplies of island drinking water. In short, like those who live in the Caribbean, these communities’ ability to survive depends on protecting their fresh water.

Extremes in the weather patterns El Niño and La Niña could double in the 21st century, compared to the previous one. El Ninos bring drought, which means Pacific communities have to desalinate water to make up for dwindling rainfall. But rising sea levels contaminate groundwater supplies and aquifers, which basically means Pacific Islanders have it coming from all sides.

Wait, there’s more. Too much freshwater is bad, too. Under a higher-warming scenario, rainfall in Hawaii could increase by 30 percent in wet areas by the end of the century. Think that’s good for dry areas? Think again! Projections suggest rainfall decreases of up to 60 percent in those. So more rain where rain isn’t needed and less rain where it’s dry. Great.

To end things on a sad note — because why the hell not — the National Climate Assessment states that “nesting seabirds, turtles and seals, and coastal plants” are going to be whacked by climate change. :(