Adrienne Titus was heading back to her parents’ village on a sweltering afternoon in early July when she saw the dead salmon. She had been fishing upstream with her mother on the banks of the gorgeous Unalakleet River, which Chinook, pink, coho, and chum salmon travel up every year in order to spawn. Down closer to the village of Unalakleet, though, there were no signs of life on the water that day — just hundreds of soft bodies floating belly up.

Titus, a 39-year-old Iñupiat woman who lives in Fairbanks but grew up in Unalakleet, had never seen anything like it before. Neither had her mother, or any of the village elders that they asked in this small fishing community on the shores of the Norton Sound in the central Bering Sea.

“It was scary,” Titus said. “It put fear into us.”

Similar reports of dead pink salmon came in all across the Norton Sound that week as temperatures soared into the high 80s and low 90s during a statewide heatwave that “re-wrote the record books,” according to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration. Fisheries biologists say that’s no coincidence: Warm water stresses the animals out, and temperatures above a certain threshold can kill them. In a statement issued on July 11, the Norton Sound Economic Development Corporation warned that the salmon die-offs appeared to be part of a “larger ecosystem-level shift” taking place due to rising temperatures.

It’s just one of countless alarming signs of change Alaskans have experienced lately. July was Alaska’s hottest month in recorded history, thanks in part to that torrid heat wave. March through August? The state’s warmest six-month period, with temperatures hovering 6.4 degrees F above long-term averages. From vanished sea ice to skies choked with wildfire smoke to animals appearing where they shouldn’t or not appearing where they should, the impacts of a fast-warming climate were visible everywhere residents looked.

“I have just felt overwhelmed trying to keep up with everything this year,” said Rick Thoman, a climate scientist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy who co-authored a report in August summarizing the environmental changes unfolding across the state. “It’s been running from one fire to another, almost literally.”

Retreating sea ice

Anne Jensen, an archaeologist who lives in Utqiaġvik, a city of 4,400 on the northern tip of Alaska’s North Slope, said that the loss of sea ice is being felt especially hard by her community. There, Iñupiat hunters hold a subsistence whaling season in the spring and the fall, catching a small number of whales each year that represent both a key source of food and an important cultural tradition.

In the spring, hunters set up camps on the ice where they butcher the animals they catch. But with temperatures in Utqiaġvik rising at some of the fastest recorded rates on Earth, the so-called landfast ice is breaking up earlier in the spring, reducing the amount of time it can be used for hunting. The ice that’s present is becoming weaker and more dangerous.

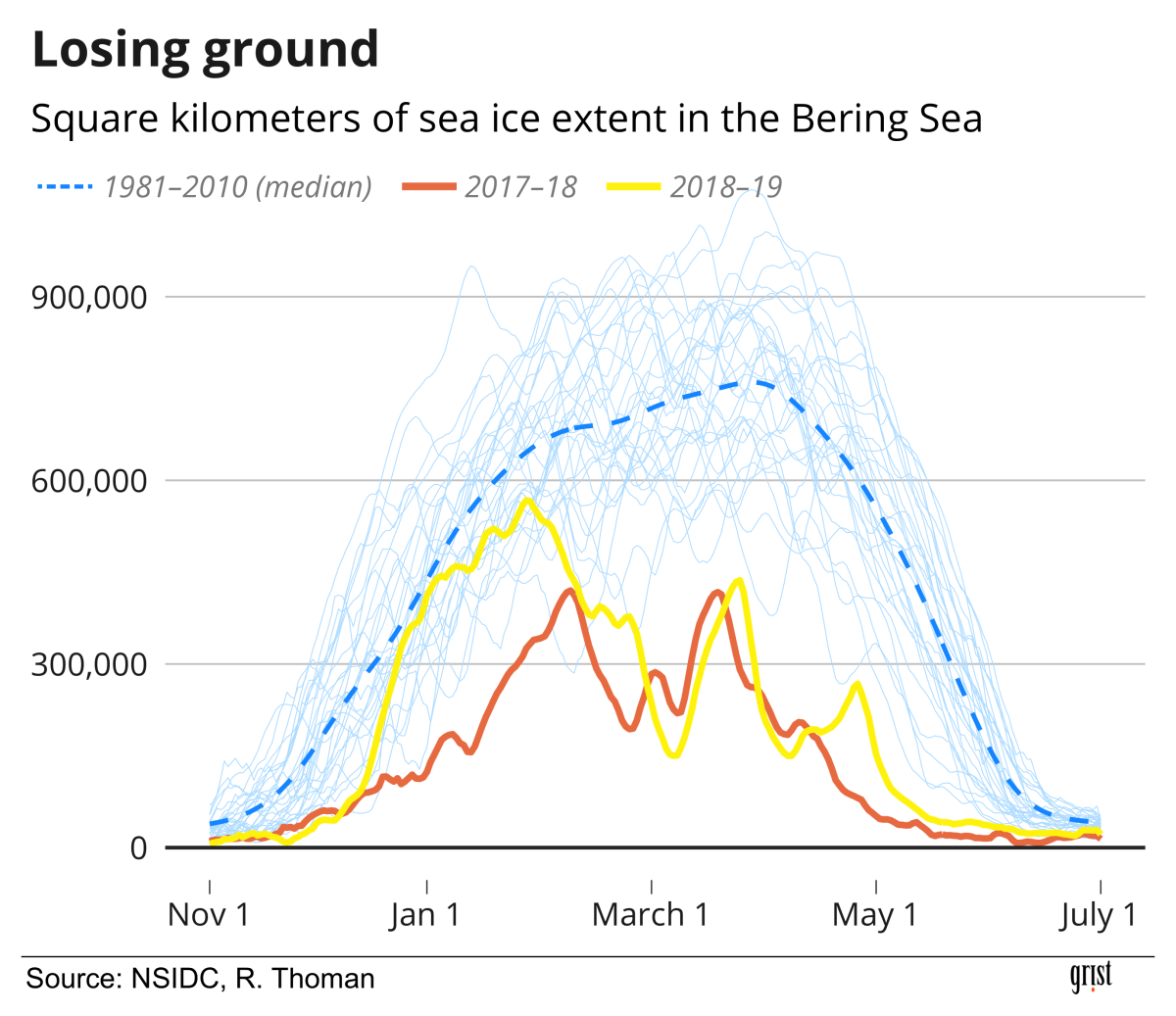

Zachary Labe (w / data from National Snow & Ice Data Center, Boulder, CO)

Fall hunting season occurs over open water before the ice freezes to the shore. But while in the past, the edge of the sea ice might linger 100 miles from the coast around its yearly September minimum, last month the ice bottomed out at its second-lowest ice minimum on record. As of last week, you’d have to travel about 400 miles north of Utqiagvik to find any, said Mark Serreze, a scientist with the National Snow and Ice Data Center. “This is part of the pattern we’re seeing now,” Serreze said.

The longer open water season is allowing the winds to stir up bigger waves, which can create additional hazards for hunters. Some hunters are also reporting that they have to travel farther from shore to find whales in the fall due to increased shipping activity as the ice disappears.

The food supply isn’t all that’s being affected by the loss of ice: So is the very land people’s houses sit on. Across the North Slope, shorelines are eroding as warm ocean waters gnaw away at thawing permafrost bluffs. In addition to impacting modern-day infrastructure, this is causing many of the coastal archaeological sites Jensen studies to deteriorate rapidly.

“It’s pretty scary,” Jensen said. “The changes are major and happening quickly.”

Vanishing fish

Further south in the Bering Sea, the ice broke up early this spring after struggling to grow throughout the winter. By mid-May, it was nearly gone. The dearth of sea ice, which would have been unprecedented if something very similar hadn’t occurred in 2018, is affecting the so-called “cold pool,” a vast region of near-freezing water that develops at the bottom of the Bering as sea ice forms above, providing a habitat for species like Arctic cod and snow crabs.

Last year, for the first time on record, the cold pool didn’t form, and scientists saw large numbers of southern species, like pollock and Pacific cod, move into areas of the northern Bering Sea “where we really never expected to see them,” according to Lyle Britt, who heads up the Bering Sea Bottom Trawl Survey Group at NOAA Fisheries. This year, a cold pool did form but it was “effectively so small that it was really not a barrier to fish movement,” Britt said. Once again, large numbers of fish from more southern latitudes appear to be invading the region.

What this will ultimately mean for the fisheries of the Bering is unclear. But this year was a dismal one for crabbers in the Norton Sound, who caught only a little more than half of their annual quota, which was already the lowest the state had set in 20 years. Poor ice conditions were at least partly responsible for the bad haul, according to Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game.

“It’s definitely been alarming to the crab harvesters noticing the changing conditions in the Bering,” said Jamie Goen, executive director of Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers, a trade organization that represents crabbers further south. Their members have been catching their quotas, Goen said, but as is the case up north, the quotas are at historic lows.

Historic wildfires

Inland, Alaskans have been contending with wildfires. Fires torched some 2.6 million acres across the state this year, and although that’s far from Alaska’s worst wildfire season — in 2004, a staggering 6.5 million acres burned statewide — 2019 will go down as one of the ten largest wildfire years since 1940. Big years like it are occurring far more often than they used to.

With this summer’s fires came loads of smoke. In early July, residents of Anchorage experienced their first-ever dense smoke advisory as particulate matter from the Swan Lake Fire, a lightning-sparked blaze on the Kenai Peninsula, wafted over the city. Around the same time, lighting-sparked fires in central Alaska sent smoke billowing over Fairbanks, reducing visibility to a few feet and creating some of the worst air quality in the world.

Alaskans also experienced some dangerous late season flare-ups this year, fueled by hot, dry conditions that prompted the state to extend fire season from the end of August to late September. These included the McKinley Fire, which exploded in size north of Anchorage on August 17 and destroyed more than 100 buildings before it was contained. That very same day, the Swan Lake Fire got a second life when gusty conditions reignited the flames. It would grow to engulf an additional 50,000 acres over the next week, triggering a new wave of smoke advisories.

Fires like these are “unusual” in mid August, said John Morris, a retired park ranger with the National Park Service who’s lived in Alaska since the 1960s. Their appearance this year illustrates what Morris sees as the most striking consequence of climate change in Alaska: just how unpredictable the weather has become.

“In some ways, it’s comforting, because things are warmer than they used to be,” Morris said. “But not having the environment be as predictable makes things a lot more uncertain.”

‘The frog in the pot of water’

To Rosa Standifer, a 46-year-old Athabascan woman born and raised in the village of Tyonek southwest of Anchorage, the clearest sign that things have changed is in the salmon. Since Standifer moved back to Alaska from California in the mid-2000s, Chinook salmon have declined precipitously in the Cook Inlet, where Tyonek is located.

“Back in the day, our boats would be sunk down with salmon,” Standifer said, recalling her childhood summers spent fishing on the water with her father. “Now you’re just praying and hoping you get some.”

Sue Mauger, science director for the community-based non-profit Cook Inletkeeper, thinks climate change is at least partly to blame. Chinook, she said, become stressed out when temperatures rise above 55 degrees F, leaving them more susceptible to pollution, predation, and disease. Her research shows that summer temperatures in the non-glacial streams feeding Cook Inlet have risen steadily for decades. During the July heat wave this summer, one of the major salmon streams Mauger monitors hit 81.7 degrees F — a frightening new record. “I like to think of this as the frog in the pot of water has been simmering for a few decades, and we just had a big twitch,” Mauger said.

Asked whether she ever experienced a summer like 2019 growing up, Standifer laughed. “Oh, no,” she said. “And I hope it don’t keep getting that hot. I moved back to be cold.”