Second in a series on lessons from California’s water crisis.

“It’s going to be kind of noisy — and very smelly,” Laura Anhalt warns, laughing, as we enter our first building at the primary wastewater treatment plant in Modesto, California. She’s right: The funk of processed sewage hits quickly.

Inside, a conveyor rake scrapes crumbling, sodden paper up out of a vat of water. Nearby, a large metal mouth swallows the paper pieces and feeds them through a compactor that extrudes a solid hunk of waste nearly as wide around as a human torso. Separating out the solids — unappetizing as it smells — is the first step in cleaning the water that Modesto residents wash down their sinks and flush down their toilets every day.

Separating out the solids at the Sutter wastewater treatement plant in Modesto. (Emma Foehringer Merchant)

This process happens at thousands of similar plants all around the world. But Modesto’s sewage treatment will soon be part of a novel project: Starting as early as December, the city will sell its highly treated wastewater to struggling nearby farmers. When it’s up and running, Modesto’s experiment should be California’s largest wastewater-to-agriculture reuse project, and it will mark the first time recycled water flows through a federal canal.

In the past several years, California’s drought has cut back water supplies for many growers, forcing them to fallow fields. Though much of California has been deluged with precipitation this year, scientists warn that the wet weather won’t last. Climate change is expected to make the state’s dry-and-drenched extremes even more drastic.

To maintain the state’s agricultural might, farmers will need new water sources that won’t dry up in the next drought.

The North Valley Regional Recycled Water Program, as the project is known, will serve an area in the Central Valley, California’s most productive agricultural region. Its planners hope it will serve as a model for other drought-stricken regions of an environmentally friendly way to get water to farmers. Some environmental advocates hope so, too. The project has won the support of conservation groups like Audubon California and Ducks Unlimited because it will also provide water for the state’s wildlife refuges.

But getting the project off the ground hasn’t been easy. Nearby water suppliers criticized and challenged the proposal to reroute water, fearing it might affect their own supplies. Documents obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request show that the water district pushing the plan had to delicately negotiate compromises to coax the project forward, in some cases offering other districts a cut of their water.

In California, it seems, the best way to solve disagreements over water is with more water.

The city of Modesto has two wastewater treatment plants, called Sutter and Jennings, about eight miles apart. Anhalt, or as she quippily labels herself, “the dirty water gal,” has managed both for nine years. She has a cat tattoo on her left calf and a quick laugh. She’s lived in California her whole life, apart from a stopover in another drought-stricken locale, Australia.

After a visit to Sutter, where the first round of water treatment takes place, Anhalt drives me to Jennings in her red Lexus, a cat air freshener dangling from the rearview mirror. We pass row after row of spindly young trees that will eventually produce lucrative walnut and almond crops — if farmers have enough water to keep them alive.

Many of the orchards display signs with the words “Worth Your Fight” and an image of a water droplet. “Ah, water!” Anhalt exclaims when I ask about them. She says they’re part of a campaign to defend farmers’ water supplies in the Central Valley.

Modesto’s two plants pump out nearly 15 million treated gallons a day. The initial processing at Sutter strips out solids. Then the city pumps the water to Jennings, where further treatment breaks down organic matter and any remaining solids with digesting protozoa “bugs.” Last, the water is zapped with UV lights to disinfect it.

UV lights zap bacteria out of treated water at the Jennings plant. (Emma Foehringer Merchant)

Jennings is a vast complex that stretches over 5,000 acres, 1,000 of which are oxidation ponds extending nearly as far as the eye can see. The ponds look more like a nature preserve than a sewage treatment facility, attracting birds and birders.

Anhalt tours us around a number of structures at Jennings — sometimes testing doors to see if they’re unlocked, because she forgot her keys. She easily rattles off descriptions of the complicated processes at work. For her, this is second nature. She’s been working in wastewater for 23 years.

At an aromatic tank of “mixed liquor,” which contains raw wastewater and microorganisms that break down its contents, she seems pleased to be the overseer of such an enormous, complicated system. “Good stuff. It looks pretty,” Anhalt says, nodding at the brown liquid rippling with bubbles. “Not too foamy.”

Later we visit what she frames as the pièce de résistance: “You just have to see the blowers.” As we wend our way through another building, a muted buzzing sound slowly builds to a deep whooshing. These machines aerate the membrane tanks to encourage processing.

“I’m so excited,” she smiles. “I love the blowers.”

After treatment is done, Modesto uses the water to irrigate city-owned land and sends any left over into the San Joaquin River to flow to users downstream.

By the end of the year, that should change. A refurbished pump station at Jennings will send most of the wastewater into a new $100 million, six-mile pipeline. That will feed into the Delta-Mendota irrigation canal, which ferries water to farmers as part of the Central Valley Project, a federal system that manages and doles out water in the area.

The Delta-Mendota Canal. (Dave Parker)

Ultimately, Modesto’s wastewater will reach farms about 20 miles away in the northwestern San Joaquin Valley, where growers on 45,000 acres of farmland in the Del Puerto Water District have struggled to water their crops since the drought began. By 2045, when all phases of the project are complete, these farmers should be receiving nearly 60,000 acre-feet per year from the North Valley project — enough to fill roughly 30,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Anthea Hansen, head of the Del Puerto Water District, is the one who pulled the entire project together. She’s been working nonstop for the past seven years to bring more water to farmers there.

After the drought started in late 2011, and restrictions set aside more water for wildlife, allocations from the Central Valley Project to water districts in the San Joaquin Valley plummeted. The Del Puerto Water District received zero percent of its contracted supply in 2014 and 2015, and just 5 percent last year. In 2017, already a historically wet year, it will receive its full allotment, but Hansen expects that to drop as soon as next year.

Because the district hasn’t been able to rely on water from the Central Valley Project, for the past several years Hansen has had to negotiate water purchases within California’s tricky water-rights system. The district has been buying excess surface supply when it’s available, and has also purchased groundwater from other districts at high prices. “We’ve survived on supplemental water, and about one quarter of our irrigated acreage is fallowed,” Hansen says.

The water from the North Valley project will make an enormous difference to the farmers in her area. “It pretty much changes the course of the future for our district,” she says.

Daniel Bays is one of those farmers. His grandfather moved to the area in 1957, and the family now grows apricots, walnuts, lima beans, tomatoes, and melons at Bays Ranch in Westley. His farm has struggled to get by with the minimal supply. He’s also used groundwater, but it’s often salty and can cause land to sink if pumped to excess. “It’s expensive, poor quality, and there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to get it when you need it,” he tells me.

Water from the North Valley project will still be expensive — potentially two or three times the price of Central Valley Project water — and it will only meet about a third of the water district’s need. But it will at least be reliable and high quality, something farmers haven’t been able to count on in recent years.

Bays points out that this new water source is not going to dry up, because Modesto will keep producing wastewater: “People are flushing their toilets every day and taking showers,” he says.

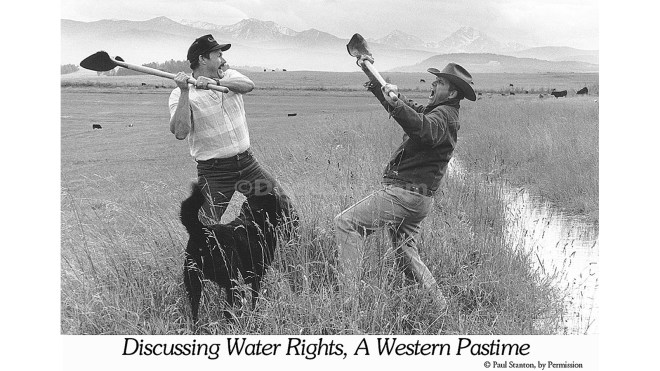

Above his desk at Turlock City Hall, Garner Reynolds has taped a photo printed out on computer paper. It shows two men in jeans standing in a field, menacingly wielding shovels at each other. The caption reads: “Discussing water rights, a Western pastime.”

Turlock is also involved in the North Valley project, as is another nearby city, Ceres. Turlock is building its own 7.5-mile pipeline, at a cost of $20 million to $30 million, to transport wastewater from its primary treatment plant, as well as some wastewater from Ceres, over to Jennings. It should be complete in December 2018.

Reynolds, Turlock’s regulatory affairs manager, sports a goatee and a bright aqua dress shirt. Like most of the people I spoke with about the North Valley project, he said it would be a win-win for Del Puerto growers and the participating cities, which will get paid for their recycled water. “It works for everybody,” he says.

But reaching that point took a lot of effort. Negotiating water rights and diversions is notoriously arduous in California. The North Valley deal involves the three cities, the Del Puerto Water District, Stanislaus County, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Still more parties had to be mollified along the way.

Westlands Water District, the biggest in the country and among the most powerful, argued that Modesto’s diversion of water away from the San Joaquin River would cut into its supply. The district also worried that the recycled water might lower water quality in the Delta-Mendota Canal, which delivers water to Westlands through the Central Valley Project.

The oldest water district in the state, Turlock Irrigation District (a body separate from the city), also raised concerns. Emails obtained through a FOIA request show that in March of 2015, a lawyer representing the district sent comments to Modesto and the Bureau of Reclamation, claiming the environmental impact report for the project was inadequate and did not properly assess how it would affect groundwater.

These kinds of quibbles can delay projects for months or years while water districts and agencies negotiate a solution. It fell to Hansen to break through many of these logjams and keep the project moving forward, the emails show. She repeatedly emphasized the urgency of the situation, knowing how much the farmers in her district needed water.

“Sooner is better,” she wrote in an April 2016 note to the Bureau of Reclamation project lead, pushing to get paperwork completed. “I’m like a cat on a hot tin roof right now.”

To quiet the complaints from nearby water districts, Modesto agreed not to use any water from the Turlock Irrigation District or the Turlock Subbasin to irrigate its ranchlands. And the Del Puerto Water District brokered a deal to deliver 500 acre-feet per year to Westlands after the North Valley project kicks off.

Even though the lengthy bargaining process has been tiresome, Hansen says it’s worth it for a project that will sustain a way of life in an area where most growers are small family farmers.

“We figure out how to work through the complicated system in California to get the water moved from point A to point B,” she says. “It’s very difficult, it’s fraught with heavy levels of environmental documentation and a lot of cost to make it work, but it helps us to survive.”

“There’s a lot of things with California’s plumbing that I wish were different,” she adds.

But if all goes according to plan, at least no growers will be brandishing shovels at one another.