Five months ago, one of the country’s ten largest electric utilities told regulators in Minnesota that it needed three new natural gas power plants to handle peak energy demand. This week, the same company’s Colorado division announced plans to use more solar power because it is cost competitive with gas.

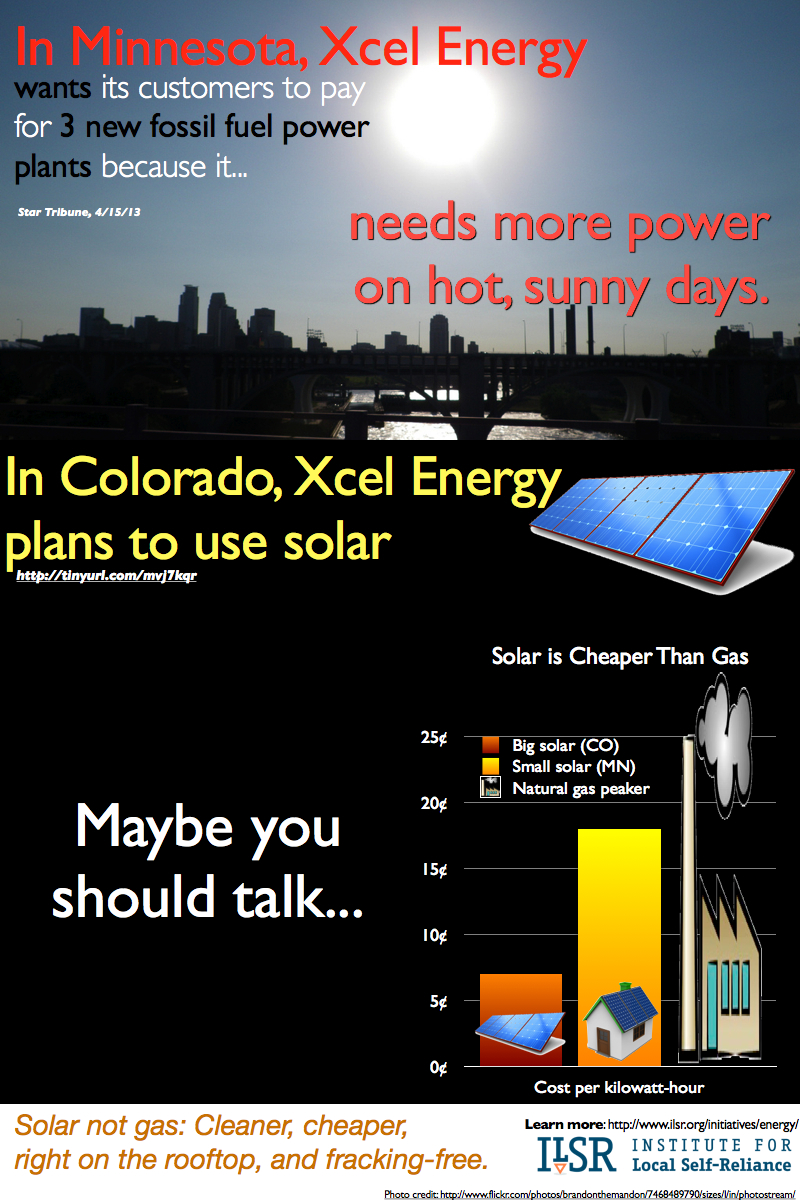

Maybe they need a memo to share the news: solar is cheaper than gas. A lot cheaper. Big or small.

The city of Palo Alto, CA, recently signed contracts to buy solar energy from utility-scale projects for 7¢ per kilowatt-hour. This is on the heels of solar contracts signed by big utilities in California to buy large-scale solar for 9¢ per kilowatt-hour. (For context, in most parts of the country, residential customers pay about 10¢ per kilowatt-hour of electricity).

But even small scale solar is competitive with natural gas power for supplying energy when the grid needs it most.

Take the Minnesota example. Xcel’s April 15 filing [large pdf] with the state’s public utility commission asks for 600 megawatts of new generating capacity from “single cycle” natural gas power plants. The California Energy Commission estimates that the cost of electricity from these power plants ranges from 28 to 65¢ per kilowatt-hour. The cost of energy is high because the gas power plants are often on and running in anticipation of being needed, consuming gas to keep the turbines spinning all the while.

In comparison, electricity from a residential rooftop solar installation in Minnesota (quotes available now at $4 per Watt!) and with the 30% federal tax credit, will produce electricity during high demand peaking periods (or whenever the sun shines) for 18¢ per kWh.

You read that right: rooftop solar in Minnesota costs 36-75% less than natural gas power plants in delivering peak energy. Solar not only meets this peak need at a lower per kilowatt-hour cost, but also without the harmful emissions from running a power plant on standby (or fracking its fuel out of the ground).

What’s important to keep in mind when talking about solar and electricity prices is that solar energy production tends to align very well with the highest energy demand on a utility’s system. It doesn’t have to be cheaper than a nuclear power plant built in 1965, it just has to be cheaper than the next kilowatt-hour the utility needs at 4pm on a hot, July afternoon. For many utilities (like Xcel, one of the 10 biggest in the U.S.), it is. For many others, it will be soon, without subsidies.

And don’t forget, utilities buy power plants for 30, 40, or 50 years. With costs dropping by 10% per year, if solar power’s not cheaper now, it will be long before a new fossil fuel power plant is paid off.

There’s one more facet to this story. As solar gets cheap, more and more customers are looking to go solar to reduce their energy bills (and their reliance on corporate, monopoly utilities). Not only does this mean less revenue for Xcel (although independent studies show a utility’s benefit outweighs this lost revenue), it also means no shareholder return, which Xcel and other monopoly utilities only get when they build new infrastructure. Xcel’s Colorado plans suggest the utility is wising up, and that the era of customer-owned solar only lasts as long as people are willing to raise holy hell or legislatures are willing to tell them to do the right thing.

So the utility shift to solar is both bad and good. The bad news is that locally owned solar pours piles of cash into local economies, and utility-owned solar is going to suck it right back out again. The good is that even an anachronistic, monopoly utility can figure out the financial advantages to clean energy, and we need a lot of it to save the climate.

Game on.