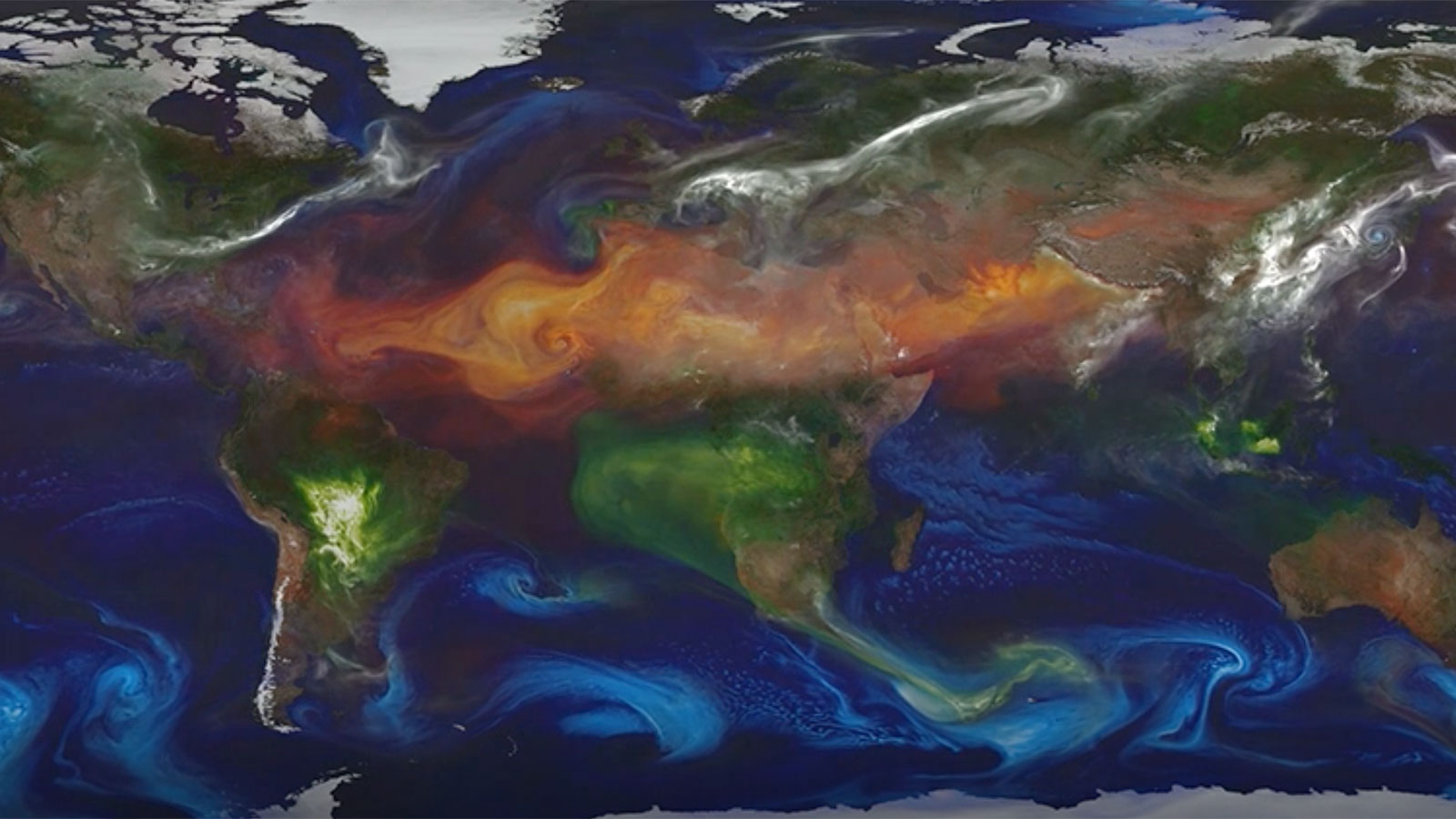

Pollution knows no borders. Particulates from Asia can blow across the Pacific Ocean, creating smoggy skies in the American West. Fish contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls — a type of commercially produced chemical that’s been banned for decades — travel to Canada’s remote Arctic region causing toxin blood levels to spike in Inuit children. Nearly 70 percent of imported produce tested by the U.S. Department of Agriculture tested positive for pesticide residues.

These are a few of the examples from a new report from Pure Earth, an international nonprofit, that outlines how toxins travel from one part of the world to another through air, water, food, and manufactured products.

“We have to be concerned about what the international community is doing,” Gina McCarthy, the former EPA administrator under Obama, told Grist.

“We can no longer grow [economically] in the United States and throw our waste elsewhere and think that that’s meeting our global obligation,” said McCarthy, now the director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard’s school of public health.

McCarthy believes the United States has a real opportunity to be a leader in global efforts to reduce pollution, but she says the current administration is moving in the wrong direction by pulling out of the Paris Agreement and loosening regulations meant to keep people safe — for example, the recent Environmental Protection Agency proposal to roll back Obama-era mercury and toxic air standards.

“There is so much we can learn if we don’t think in isolation,” McCarthy said.

Countries tend to take their own approaches to regulating pollution. Many wealthy ones, like the United States, cut costs by outsourcing high-polluting industries to countries with weak environmental regulations. “The greening of U.S. manufacturing over the past several decades may be partially caused by a growing flow of ‘brown’ imports from poor countries,” Yue Maggie Zhou, a professor who researches multinational corporations at the University of Michigan, wrote in The Conversation.

In 2015, health issues caused by pollution took an estimated 9 million lives worldwide, representing roughly 16 percent of all deaths worldwide, according to a 2017 Lancet report. The vast majority of pollution-related deaths — 92 percent — occur in low- to middle-income countries.

Air pollution, which reduces the average person’s lifespan by one year, is the most well-documented form of transboundary pollution, according to the Pure Earth report. But pollution, as the report states, “crosses national borders in many guises, both visible and invisible.” Ten percent of soil in China’s farmland is polluted by heavy metals like cadmium and mercury, according to study based on 456 published papers. This contamination comes from a number of sources, including mining, irrigation by sewage, urban development, and even fertilizer application.

We need to trace pollution back to its source and provide services to stop the problem where it’s occurring, said Richard Fuller, president of Pure Earth, who’s been working to reduce pollution in low- and middle-income countries for over 20 years. When a problem is solved at its source, he said, it’s solved for everyone.