Many green leaders joined the Washington establishment and Big Business this week in applauding President Bush’s nomination of Henry “Hank” Paulson — Wall Street titan and heavyweight conservationist — to replace outgoing Treasury Secretary John Snow and spearhead the administration’s economic policy making. But while Paulson proved popular in many circles, a handful of right-wing groups bristled at the pick, claiming that Paulson’s pro-environment views were too radical.

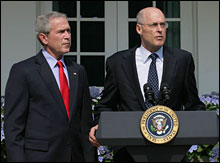

President Bush introduces Hank Paulson.

Photo: White House.

Much vaunted as chair of the investment firm Goldman Sachs since 1999, Paulson is less known for his role at The Nature Conservancy, the world’s largest conservation organization. He joined the group’s board of directors in 2001 and now serves as board chair. TNC President and CEO Steve McCormick hails Paulson as “a voice for environmental issues at the highest levels of business and government. His mark on the conservancy is indelible. He has helped us think big — very big — about our conservation ambitions.”

Paulson believes environmental health and financial well-being are inextricably linked. “The environment and the economy have been totally misconstrued as incompatible,” he told Muckraker in an interview earlier this year. “They are opposite sides of the same coin — you can’t consider one without the other.”

He’s put this view into action at Goldman Sachs. Under Paulson’s leadership, the firm has ramped up its investments in energy efficiency and renewable energy, including solar, wind, and biofuels. “We’ve made well over a billion in [clean-technology] investments,” he said. “We’re not making those investments to lose money.”

In 2004, under Paulson’s watch, Goldman donated 680,000 acres of wilderness in southern Chile to the Wildlife Conservation Society, to the consternation of a few shareholders.

Paulson also worked with environmental groups including the World Resources Institute and the Natural Resources Defense Council to develop a comprehensive environmental policy framework [PDF] for Goldman Sachs, unveiled last November. “It’s certainly one of the most far-reaching that has been developed among leading companies,” said WRI Senior Associate Jon Sohn. He said the policy statement broke ground by essentially calling for mandatory government limits on greenhouse-gas emissions and by saying the company would encourage its clients to adhere to high environmental standards.

As Paulson told Muckraker, “I believe that the best, strongest, most efficient companies are going to have the best environmental practices. It is axiomatic.” He also asserted that companies with good green reputations have a competitive edge in luring top talent: “I believe our forward-looking environmental policy makes us more attractive to younger recruits.”

A Little More Conservation

On a personal level, Paulson is known to have a strong affinity for nature. Raised on a farm in Illinois, he wanted to be a forest ranger until he went to college, according to Fortune. “I’ve seen him many times in the out-of-doors and he can’t get enough of it,” said McCormick. “He’s an insatiable bird-watcher, but also incredibly curious about the natural world in general. It’s infectious.” McCormick recalled a trip he and Paulson took to China, where they were surveying some wilderness in the Yunnan Province. “The road was washed out, our vehicle couldn’t go any farther, and most of us wanted to turn around. But Hank jumped out and started putting the road back together by hand — brick by brick — until eventually a backup vehicle came along and rebuilt the passage. He can’t be stopped.”

Paulson also gives big to green causes. He and his wife Wendy, a former TNC board member who leads bird walks in New York City’s Central Park, this spring donated $100 million of their Goldman stock to an environmentally focused family foundation. In the 2002 and 2004 election cycles, they donated $608,000 to the League of Conservation Voters, which works to elect candidates with strong environmental records, according to the Center for Public Integrity. Paulson’s remaining net worth is estimated at more than $700 million, and according to The New York Times, he’s privately expressed plans to give that wealth away.

Though reportedly a Republican — he raised at least $100,000 for Bush’s 2004 reelection campaign — Paulson is at odds with many in the GOP over climate change. He sees it as a serious problem that can’t be adequately addressed with voluntary measures, and he’s committed Goldman Sachs to making a 7 percent reduction in greenhouse-gas emissions from its offices by 2012.

“Hank has a very profound sense of what’s right and wrong,” said McCormick. “He hasn’t shied away from bringing his environmental sensibility to bear in the finance world — even in the face of criticism — and I think he will bring that sensibility to the Treasury.”

This is precisely what some right-wing organizations fear. “We vehemently oppose the Paulson nomination,” said Peter Flaherty, president of the conservative National Legal and Policy Center. “This guy has promoted environmental initiatives that blatantly contradict the interests of Goldman shareholders — policies like Kyoto that would more or less close Western economies down, would stop any growth. It’s just crazy to even consider it. So how can we trust him to promote the public interest over environmental interests?” (While Flaherty acknowledged that neither Goldman Sachs nor Paulson has endorsed Kyoto, he insisted, “The Conservancy has supported it, and Paulson’s at the head of it. That’s enough for me.”) A few other free-market groups have also come out against Paulson.

Flaherty is trying to rally opposition to the nomination, but his efforts will almost surely be in vain. Paulson is widely expected to be approved by the Senate.

Speak Your Mind and the Rest Will Follow

Though certainly green by Wall Street standards, Paulson is no radical, nor is he even necessarily aligned with mainstream environmental thinking. White House budget director Rob Portman suggested to The New York Times that Paulson might not be eager to restrict economic activity for the sake of the environment. “I would call him more of a conservationist,” Portman said. “The distinction might be that he focuses on preserving and protecting sensitive environments, sensitive land, and some of that land has endangered species in it.”

Whatever Paulson’s opinions on environmental policy, there’s no guarantee he’ll be able to play them out at the Treasury Department.

“Keep in mind that the Bush administration’s first treasury secretary, Paul O’Neill, also had strong environmental convictions, but he fought battle after losing battle to get his superiors to take these issues seriously, and was effectively shut down,” said David Sandalow, an environmental and foreign-policy scholar with the Brookings Institution.

In The Price of Loyalty, O’Neill describes a memo he sent to Bush in February 2001 with advice on developing a climate-change strategy. Needless to say, it had no impact.

Both O’Neill and Snow are widely thought to have been hired as “salesmen, not architects, of Bush policy,” said Sandalow, “so [the administration] would be significantly changing their tune if they intended to give Paulson a substantive rather than symbolic role.”

Then again, Paulson has attained such a high level of financial success and renown on Wall Street that many argue he would not accept the Treasury position without a guarantee that he would be more than a mouthpiece. “This is not a guy who is going to leave a $38-million-a-year job [as he reportedly made in 2005] and a position of widespread acclaim to get pushed around,” said Kevin Curtis, a vice president at National Environmental Trust.

Goldman Sachs spokesperson Peter Rose indicated that Paulson has no intention of being silenced on the environment or any other issue, saying simply, “He’s a man who speaks his mind.”

Conservation International Chair and CEO Peter Seligmann, who has worked with Paulson on conservation efforts in the past, observed that Paulson would be entering the fray at a decidedly different historical moment than his predecessors. “The rise of gas prices and the growing scientific evidence and consensus on global warming is changing the way even the Bush administration talks about energy and climate issues,” he said.

Seligmann contends that Paulson could even represent a tipping point within the Bush administration: “There are a number of people among Bush’s closest advisors including [Secretary of Energy] Sam Bodman, [Secretary of State] Condoleezza Rice, and even [White House Chief of Staff] Josh Bolten* who share a fast-growing interest in better environmental and energy strategy. My hope is that Paulson will raise the level of understanding around these issues within this inner circle, and rally a critical mass that will push the administration to make substantive moves in the right direction.”

That hope may seem far-fetched. But if Bush pulled out all the stops to convince a reluctant Paulson to come aboard, as has been widely reported, one would think the president would be open to hearing what the man has to say.

* [Correction, 02 Jun 2006: This article originally misquoted Peter Seligmann as saying John Bolton, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, was among Bush advisors with an interest in better energy and environmental strategy. It should have read Josh Bolten, White House chief of staff.]