The environmental and LGBT movements have more in common than you might think. They both have a boatload of science to back them up; they’re both about people’s survival; and for the past several years, they’ve been the target of several Trump administration policies.

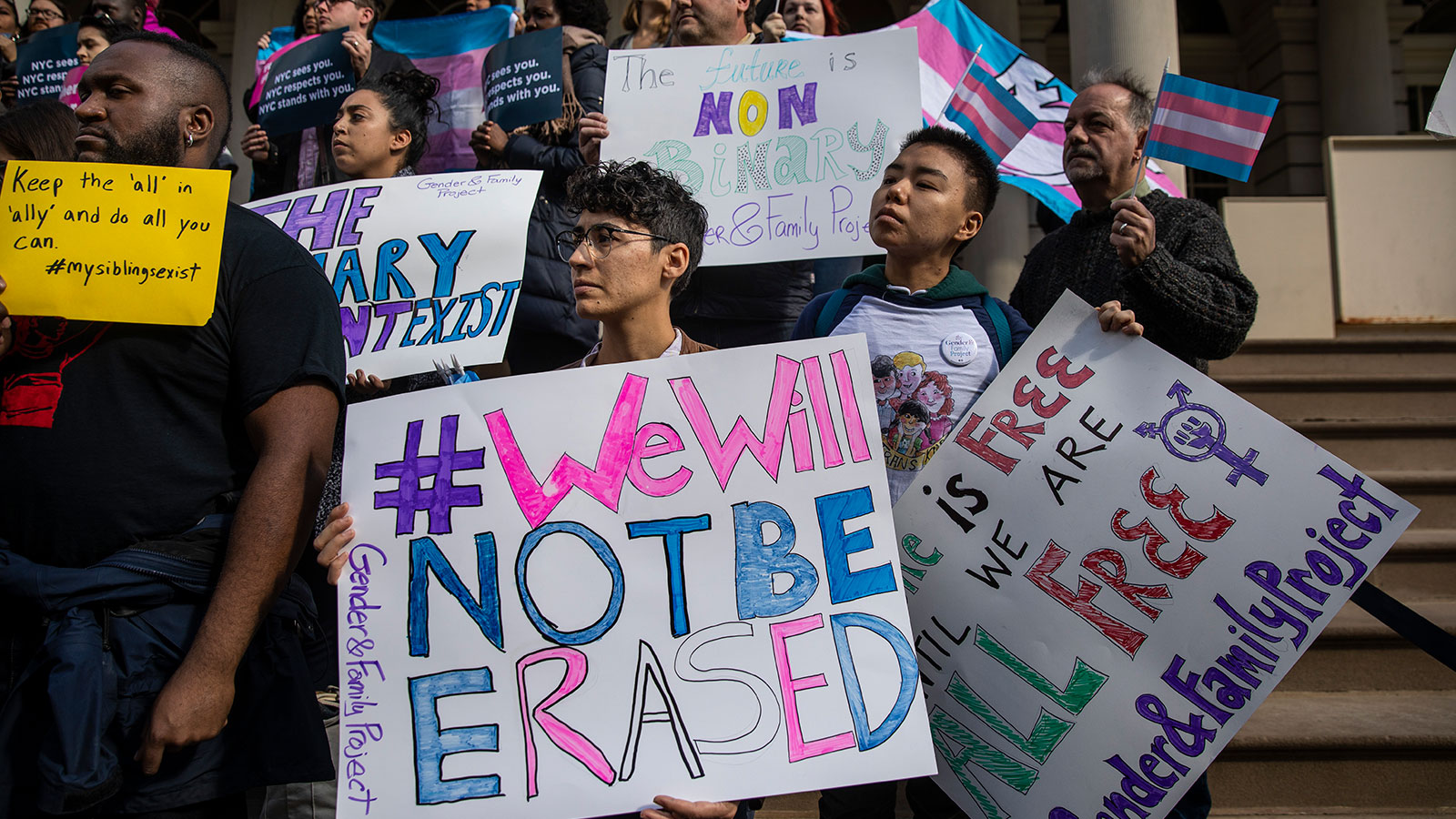

Last week, the New York Times reported on a memo from within the Trump administration that proposed limiting the legal definition of gender to either male or female, based on a person’s sex assigned at birth. That definition would drastically undermine civil rights protections for transgender people by excluding them from Title IX.

The proposed policy change hit home for many individuals, including many within the environmental movement. For the past year, Precious Brady-Davis has worked as a deputy press secretary for the Beyond Coal Campaign at Sierra Club. “As we look across the intersections, I think it pushes the movement forward,” she says. “I come from this place because I am a trans woman of color. I didn’t know anything about the environmental movement and I wanted to move more in that direction.”

Grist talked with Brady-Davis about the threats transgender and gender non-conforming folks are facing from policy, pollution, and climate change. She breaks down where she sees the environmental movement when it comes to diversity, and how the planet and campaigns to protect it can become safer spaces for everyone.

(This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

Courtesy of Precious Brady-Davis

What factors might result in higher or different exposure for transgender folks in terms of pollution and other environmental health risks?

Lots of transgender and non-conforming people who experience poverty, they’re exposed to dirty air and dirty water. And most of the time, they don’t realize that they’re living under the shadow of [these exposures]. It starts with poverty. (Transgender people experience poverty at a rate more than double that the U.S. population overall)

There’s also the life expectancy of trans individuals (a 2014 report said that trans women have a life expectancy of between 30 and 35 years). So when you have a life expectancy of 30 years or so, you don’t have a chance to actually start to build a long-term frame of healthy living for yourself.

The harassment that trans folks face from the moment that they walk out the door — like, will I be seen as the person that I want to be seen as? Am I safe? All of that has an effect on the lives of trans people, especially those who are most marginalized.

It’s been documented that gender-based violence increases after climate disasters like hurricanes. Can you talk a little bit about how you see this issue play out in the transgender community?

Like climate change, we can see the catastrophic effects of gender-based violence right before our eyes. (Both intimate-partner violence and sexual violence are associated with displacement and impoverishment following natural disasters.) We see the murders. We see the terrible storms. We see the dirty air and the dirty water. We see animals dying and our forests being devastated. So I think we have to see transphobia with the same kind of urgency. There were 28 murders reported in the U.S. transgender community in 2017 (the highest it’s been in at least five years). I think that it’s important that we see [trans survival] as a public health issue that has to be addressed from a systemic and environmental policy place.

There are so many economic resources put behind climate change. There’s so much science behind it, but I don’t think the same effort is put into addressing gender-based violence. Climate change takes us to the point that we realize that our survival is at stake, and so I feel that on the flip side it can be said for trans people.

Climate change is something that we’re anticipating and we’re currently seeing the effects of. So I think we need to put the same resources, and care, and the science that we put into climate change into addressing this behavioral issue of gender-based systemic violence. We have to start collecting relevant data regarding these intersections and the impact these factors have on marginalized communities.

How would the Trump administration’s proposed interpretation of Title IX, which would effectively define transgender people out of existence in federal policy, affect transgender individuals when it comes to their environment and health?

If you say that you are going to get rid of an individual’s identity, that is system-based violence. And so I think it starts there. It starts with defining a classification of people as un-American and that is not who we are. We are a democracy. There are 1.4 million transgender Americans. It could be catastrophic to those who are most marginalized.

The environmental movement has been criticized for not being more diverse and inclusive. Do you see that changing? What has been your experience in this space as a trans woman of color?

With Sierra Club, we are a really diverse organization and I see other queer and gender non-conforming people in the organization, and we feel seen, we feel heard, and our voices are lauded. When I started [working here], it never ever came up that I was trans at all. It was never a question in the process of my hiring, it was about my skills.

In terms of the larger [environmental movement], I think they can do better. I think there could be more voices and more experiences included. I see a wide range of gender diversity but in terms of race and ethnicity and socioeconomic status, I think that there is room for improvement. Diversity is not a monolith and neither are trans people. That’s one of the reasons I love the work that I do, that I bring such a unique perspective to working with all different kinds of communities.