Continued from last week …

Soon, it’s hairnet time. We pass through the double doors that separate the break room from the plant itself. The building looks big enough to hold several jumbo jets, and is divided into a tasting area, a storage area that holds the green as-yet-unroasted beans that arrive at Equal Exchange in burlap bags, and a roasting area featuring an enormous red roaster.

Soon, it’s hairnet time. We pass through the double doors that separate the break room from the plant itself. The building looks big enough to hold several jumbo jets, and is divided into a tasting area, a storage area that holds the green as-yet-unroasted beans that arrive at Equal Exchange in burlap bags, and a roasting area featuring an enormous red roaster.

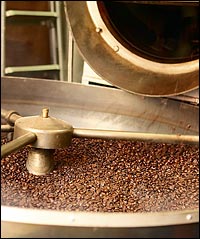

The green, unroasted beans are dumped into one of eight hoppers, then mixed at the roaster’s discretion so they achieve the right blend of beans for the type of coffee being roasted that day. The entire contraption is controlled by a modest laptop computer, lending the whole endeavor a kind of mad-scientist feeling, like those giant weather-changing machines movie villains use to hold the world hostage.

On the other side of the plant are rows and rows of beans that have been bagged for delivery to stores and other retail customers. The sheer quantity of coffee is overwhelming. Rodney explains how quickly and dramatically Equal Exchange has grown: Over its 20 years, the co-op has grown on average more than 30% annually, and since just 2002 it has doubled to its current size of $23 million.

After seeing the coffee-roasting area of the plant, we retreat to the break room again. Rodney describes the other commodities Equal Exchange sells, and offers me some organic chocolate. I take some just to be polite — in the past I have found most (though not all) brands of organic chocolate disappointing. I’m pleasantly surprised when it is smooth and lacks the “burnt” flavor often found in organic chocolate. I’ve never been sure whether the organic chocolate I haven’t enjoyed is the result of being single source or just inept over-roasting. When I mention I don’t usually find organic chocolate as good as EE’s, Rodney explains that they hired a Swiss chocolatier who insists they use a blend of cocoa beans — so EE procures cocoa from two different sources. Equal Exchange supplies the chocolatier with organic Fair Trade sugar as well.

We spend a little bit of time discussing EE’s business structure and co-op organization. “You don’t need to leave democracy at home when you come to work,” Rodney comments, and explains that an interest in international development led him to work at EE: “I was pursuing a degree in international development and was interested in joining the Peace Corps, but even before I could get around to doing that I found myself wondering if the potent power of business could be harnessed to affect social change. That led me here. I came to work at Equal Exchange and I find the work to be both useful and interesting.”

All employees have a chance to visit one of the farming communities with which they trade after working at the company for two years. This is done to strengthen the company’s ties to the farmers and to provide a greater depth of understanding of the agricultural end of the business.

As we continue our talk in the break room, a woman dressed as a sheriff and a guy dressed as a Thai kick boxer walk by.

I had just read an article by Umbra about what to hand out to kids on Halloween, and that made me wish EE made tiny chocolate bars like the Hershey ones. “Wait right here,” Rodney says, and returns a minute later with a handful of tiny chocolate bars. “I’ve got to tell Umbra!” I say.

When Rodney takes me back to his office to give me some brochures and an annual report, he shows me an email about Nestle, wherein the company explains that their guidelines about using child labor in producing chocolate are merely “aspirational.”This seems particularly poignant to me on this day when American children are out trick-or-treating — the chocolate they receive may have been produced in part through the labor of children their own age.”

I resolve to try to buy Fair Trade chocolate exclusively from now on, rather than what’s usually commercial available. The fact that Equal Exchange’s chocolate is delicious makes this decision even easier, and I break off a few more pieces of their milk chocolate and hazelnut blend as I sit in traffic on the way home.

As I drive home I think about my own assessment of eating locally vs. using products brought from afar (which can mean from California as well as from Peru). My opinion is influenced, in part, by having worked and cooked in a Colonial-era museum where I taught Colonial Living Day Camp. Dozens of 12-year-olds came to the museum (a former inn, and yes, George Washington slept there) where we churned butter, baked Snickerdoodles, and strung apples for drying above the mantle of the large fireplace where I did open-hearth cooking.

The foods eaten by the people who lived and worked there in Colonial days would have been largely local — crops they grew, meat they butchered themselves, and cider they pressed. Not only did they rely heavily on local foods, but they put a lot of time, energy, and resources to putting food by for the winter months. I am unsure how much pickling went on (something to put on my list of things to research) but smoking, drying, and other forms of preserving food were frequent. Even they used imported goods, however — tea and sugar when they could get them, and exotic spices that they kept in a small multichamber spice box. The combined smell of the spices was intoxicating, and I always savored the moment when I got to open the box and take that first magic breath.

This was also the era of the triangle trade: slaves, molasses, and rum. It sometimes seems to me that the whole weight of human history is about trade-driven travel and exploration. Right after showing up to ask, “So, where do you keep all your gold?” the next question was always “Whaddya got to eat?”

By the same token, I understand that life as we live it in America today is complete anomalous even by the trade-mad standards of the past — never before have so many products been available so cheaply from so many different places.

So where do I come down on this issue personally? For several years in the early ’90s, I tried really hard to eat only local produce, even in winter. I missed eating fresh salads and relied heavily on roasted root vegetables and greens for braising. I still drank orange juice and used lemons in my cooking, and of course drank gallons of tea (which I consider my birthright as a person of super-pasty Celtic descent), but I otherwise limited my fresh produce purchases.

Then, one day in December, I had the urge to bake a peach pie, so I used some canned peaches. It was delicious, and I really couldn’t come up with any good reason why I shouldn’t used canned foods. They required extra energy at the time that they went through the canning process, and had to be transported to my local market (and then by me to my house), but they didn’t require ongoing energy like frozen foods, and while they lost some of their nutritional value going through the heat processing necessary to can food safely, they still retained the majority of it.

For the moment, I come down sort of in the middle of all this. I don’t buy fresh strawberries or melon when they aren’t in season locally, but I do buy lettuce, cukes, and tomatoes. I buy bananas now and then, coffee once in a while, and tea on a daily basis. I ask myself whether it’s meaningful for me to eschew (rather than chew) strawberries in winter or if I am just being a mindless PC yuppie who doesn’t want to face the fact that she isn’t changing her consumption patterns enough to really make a difference. Is skipping melon but buying tea something I do just to make myself feel better? It’s not even really a question of whether I am living a lie, but just how much of a lie am I choosing to live?

It’s probably true that most Americans are not ready to give up their year-round access to fruits and vegetables brought to their local markets from all over the world. I think that makes products offered by companies like Equal Exchange, Oké Banana, and other importers of tropical goods a good step for now. Certainly it’s a case of “meeting people where they are,” as most Americans are not ready to go tropical-product free just yet, and indeed entire economies would implode if we suddenly stopped importing tropical products.

Maybe someday we’ll all be like the guy who grows his own coffee in Somerville. I was shocked to read recently that at the turn of the 20th century, there were 100 acres “under glass” (i.e., greenhouses) extending the growing season in the town where I live. I want to interview the local historian whose specialty is the history of local farms to find out whether it was the introduction of cheaper imported foods or the rising value of real estate that stopped local farmers from growing produce in greenhouses.

Still, the specter of the weather-changing machine keeps popping into my mind, and the knowledge that, for all intents and purposes, we are our own villains, driving our own little weather changing machines every day. Will we one day (perhaps sooner rather than later?) wish we hadn’t spent all that fossil fuel moving bananas and coffee around? We can blame a lot of the world’s problems on other people, governments, and traditions, but this is an issue that’s under our own control every day.

When I asked Ed Doyle, a board member of Chef’s Collaborative, what he thought about people’s efforts to integrate sustainability into their lives, he replied, “What’s the right amount of effort to put into sustainability? More than you were doing before.”

I think that’s a good place to start. I also know that I need to learn more about people adhering to a “100 mile diet” and what their lives and choices are like.