Earth Day highlights the need for a sustainable energy future, and experience suggests that there are only three meaningful choices for communities trying to increase local control of a greener energy future. But the three policies – deregulation (“customer choice”), municipal aggregation (“city choice”), and municipal utilities (“city ownership”) – are not equal. Two recent articles highlight the relative value of these policies quite clearly.

The Citizens Utility Board (CUB) of Illinois, a nonprofit ratepayer advocacy organization, just released a report on the results of electricity deregulation and municipal aggregation.

Deregulation or “Customer Choice”

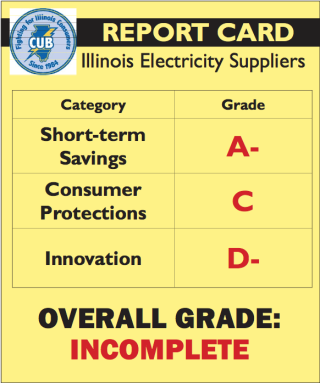

CUB didn’t think much of deregulation (report PDF). They noted that while short-term savings on electric bills were significant (customers of ComEd and Ameren Illinois saw rate decreases of about 4.5¢ and 1.5¢ per kWh, respectively, for switching to a different supplier), these savings are short-lived because the incumbent utilities’ price premium will evaporate when long-term contracts expire in June, 2013. Some customers were signed up for cable-like contracts, with low initial promo pricing followed by rates in excess of 10¢ per kWh. Customers can’t just switch back, either.

“CUB is concerned that many offers it is tracking charge ‘termination fees’ of up to $175 if customers want to exit a contract early,” it said.

CUB also gave non-utility electricity providers a D- for their failure to compete on anything but short-term price savings, noting that “a more sustainable competitive model would focus on promoting energy efficient and money-saving technologies.” The industry association’s response isn’t very soothing, saying that “In other states that are further down the competitive road than Illinois, the association said consumer incentives range from half off and free power days to frequent-flier miles.”

In other words, deregulation in Illinois is mostly a marketing game with little substantive improvement in energy policy.

Municipal Aggregation (“City Choice”)

Municipal aggregation has been modestly better. Over 450 Illinois communities passed referendum for aggregation, allowing the cities to negotiate lower rates on behalf of small electric customers in their territory (combined with individual choice, nearly 2 million Illinoisans are served by non-utility providers). Rates are similar to individual retail choice contracts, but most cities have avoided termination fees and some, like Decatur, have a provision that guarantees a price match with the utility if prices fall, or a free switch back to the utility.

Some communities have even opted for cleaner energy, via purchases of renewable energy credits (RECs). Oak Park, IL, for example, has a contract supplying electricity with RECs from wind energy that offset 100% of the electricity consumption. No wind power is built in Oak Park, but an equivalent amount is added to the grid elsewhere.

In general, however, CUB notes that municipal contracts haven’t done much better than individual ones at focusing on lower cost energy via energy savings, efficiency, or demand response. Chicago’s recently signed deal is a “promising exception” (from the report):

One exception seems to be the City of Chicago’s “municipal aggregation” deal with Integrys Energy Services, which could become a model for other communities. Chicago’s plan, compared with others, employs more of an emphasis on efficiency and demand response, and it promises a coal-free portfolio for City residents. Plus, the contract contains the strongest consumer protections that CUB has seen in the state. The City has estimated that the offer could save consumers more than $100 over the course of two years, and the contract promises to meet or beat ComEd’s supply price at all times. Finally, it allows Chicago customers to exit the deal at any time, without paying an exit fee.

Municipal Utility (“City Ownership”)

Boulder, CO, may become the most inspiring example of local leadership. Citizens authorize the city to form a municipal utility in a 2011 vote and a recently released report from the city highlights the remarkable opportunity. According to the report (and taken verbatim from the Boulder Daily Camera article), a local energy utility would be able to:

- Offer lower rates to residential, commercial and industrial customers, not just on “day one” but over a 20-year time frame;

- Maintain or exceed current levels of reliability, and future investments could enhance dependability;

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions by more than 50 percent from current levels and exceed the Kyoto Protocol goals within the first year;

- Get 54 percent or more of its power from renewable resources, such as wind, hydro and solar;

- Create a model public utility that would allow for innovation in everything from energy efficiency to customer service.

The city projects it could meet these ambitious and inspiring goals in addition to making debt service on buying the electric grid with a 25% reserve fund. It’s everything CUB wants to see from municipal aggregation and retail choice, in a single municipal utility concept.

The report lays out a promising future, but It’s still not an easy lift. The cost of buying the existing grid will be determined in a hotly contested court case, with Xcel Energy’s lawyers doing their best to make the price too high for the city to take over.

Conclusion

The lessons from Illinois and Colorado should be instructive to cities with options on the table (customer choice and city choice typically require state-level authorizing legislation). Even without these options, the expiration of long-term franchise contracts with utilities may provide cities with leverage to improve their energy future. A campaign in the city of Minneapolis, MN, for example, hopes to use the franchise negotiation to help the city council leverage more clean, affordable, reliable, and local energy. But the big gains come from the big lift, and – if successful – Boulder may set a new standard for sustainable public utilities.