Rockaway peninsula is a sliver of land roughly 10 miles long and half a mile wide that juts out from the New York City borough of Queens. Locally, it’s known for its beautiful beaches, its isolation from the rest of the city, and for being especially hard-hit by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Today, the Rockaways are in the news for a different reason — they are the proposed end-site of a new 23-mile pipeline that would run beneath lower New York Bay, carrying fracked natural gas from Pennsylvania to New York City.

Arlene Phipps, 64, is one of many residents concerned about the harm the project could potentially inflict on the community, especially in the case of another storm. Phipps had to leave her home for years because of damage from Sandy and has struggled to re-establish her home daycare business after returning this February.

“If the hurricane did what it did in 2012, God only knows what a pipeline — if something were to happen — I don’t know,” Phipps said, her voice trailing off. “God forbid if there was ever a leak or something or an explosion.”

It’s not just residents of the Rockaways who are struggling with the project. Controversy over the Williams Pipeline has sparked something of a region-wide identity crisis. New York state is in the middle of a green makeover. Earlier this year, it was the first state to formulate its own Green New Deal. New York City is leading the U.S. in a green overhaul, passing a carbon pricing fee charging drivers in some of the most traffic-choked neighborhoods. Last week, the city council voted to pass a Climate Mobilization Act that includes bills to make infrastructure more energy-efficient.

Many activists say that, given New York’s new, greener identity, the state going forward with the Williams Pipeline doesn’t quite seem to compute. Fracking is a controversial process that involves shooting high-pressured water and chemicals deep into the earth to release hard-to-reach natural gas. It’s associated with public health threats including soil, water, and air contamination.

Critics of the project say construction of the underwater pipeline could dredge up arsenic, lead, and other dangerous metals from the seafloor. They also argue that the release of methane during fracking is a powerful contributor to a warming climate. Proponents, on the other hand, say natural gas is a cleaner source of energy than oil, and that the pipeline is needed to address the state’s energy needs. Either way, the project is difficult to reconcile with the state’s own environmental policies on sourcing natural gas — Governor Andrew Cuomo imposed a statewide fracking ban back in 2014.

“It’s incredibly hypocritical for us to ban fracking [in New York state] but then frack people in Pennsylvania,” said Lee Ziesche, Community Engagement Coordinator for Sane Energy Project, one of the New York-based groups leading a coalition to stop the pipeline from being built. “To be pushing for new fracked gas infrastructure, it’s the same as climate denialism really,” she contends, “You can’t say you’re a climate leader and then push these fracked gas projects.”

A Greener New York (but still not green enough?)

New York needs a lot of energy. Metropolitan New York surpassed all of the world’s other megacities (with populations over 10 million) in energy consumption, according to a 2015 report published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

One way the state plans to address this need is to invest in renewable energy. As part of the state’s 2019 Executive Budget and proposed Green New Deal for New York, Cuomo mandated that the state’s electrical grid run on 100 percent clean power by 2040. It “builds on Governor’s Environmental Record, including banning fracking,” the press announcement says. But fracked natural gas also seems to be part of the Governor’s energy plans, provided it’s from outside the state. (Of note, Cuomo has political and financial ties to Williams Companies, having hired a lobbyist from Transco, a subsidiary of Williams, to run his re-election campaign. Williams later donated $100,000 to an organization that supports Cuomo)

The Williams Pipeline is one piece of the Northeast Supply Enhancement Project proposed by the Williams Companies, which also developed the contested Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (it went into operation in 2018), and Constitution Pipeline, which was planned to run between New York and Pennsylvania but has hit several roadblocks to construction. Williams Companies says that building the New York pipeline would displace 13 million barrels of heating oil and slash tons of carbon emissions — equivalent to taking 500,000 cars off the road.

The Williams pipeline would bring New York City an additional 400 million cubic feet a day of natural gas. All that gas would increase utility provider National Grid’s capacity by 14 percent, which proponents say is necessary to meet growing demand and fulfill a city-mandated ban on using the dirtiest types of oil for heating. But the environmental group 350.org has challenged that argument, recently publishing a report that contends increased energy efficiency will ultimately lessen demand for natural gas, and that very few heating systems are left in the city that still need to switch from heavy oil to gas.

The battle over the proposed fracked gas pipeline is intensifying amid a flurry of recently introduced federal and local policies that make it unclear whether the state would have the power to stop the project, even if it decides it wants to.

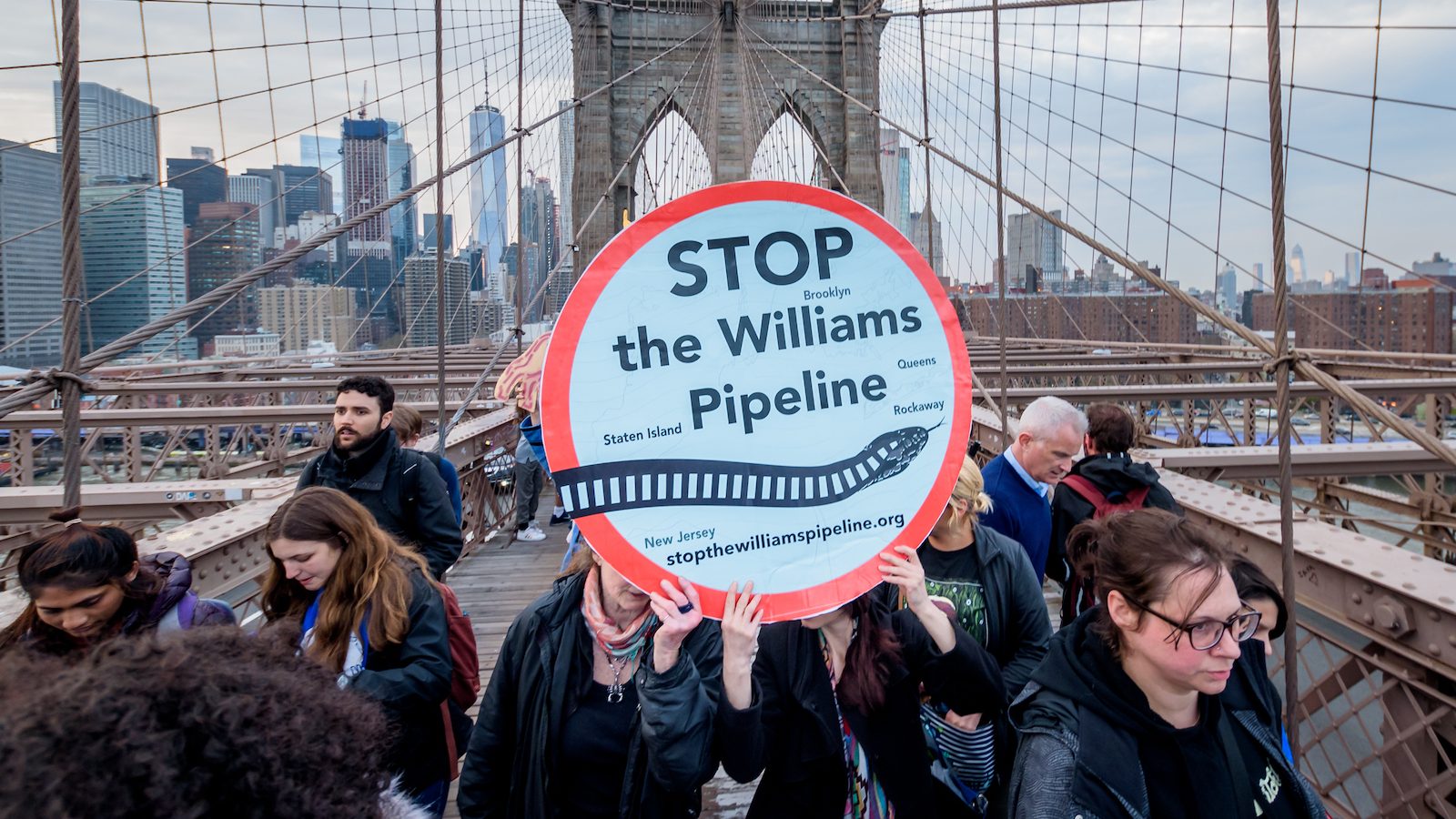

Justine Calma / Grist

On the same day last week that the Big Apple became the first city to introduce its own version of a Green New Deal, critics of the pipeline rallied at City Hall to call on Cuomo to oppose the pipeline. The Climate Mobilization Act even included a resolution demanding the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation deny the Williams Pipeline the water permit it needs to begin building.

“Governor, we are at a time when your words are not enough. We have to see action,” Jumaane Williams, the city’s Public Advocate, said at the rally. For his part, Cuomo can’t seem to catch a break from environmentalists — or proponents of oil and gas. Last week, President Trump announced two executive orders that could help remove barriers for stalled pipeline projects. One of those orders could prohibit states’ abilities to stop pipeline projects on the basis of protecting their water. In 2016, New York used this rationale to deny the Williams company permits for another natural gas project, the Constitution Pipeline.

“New York is hurting the country because they’re not allowing us to get these pipelines through,” Trump said as he announced his executive orders on April 10. “They also have a lot of energy under their feet and they refuse to get it.”

In response, Cuomo called Trump’s order “a gross overreach of federal authority that undermines New York’s ability to protect our water quality and our environment.”

The ends of the line

New York’s half of the Williams Pipeline has gotten a lot of attention, but in this case, it’s only half of the story. The Empire State already brings in fracked gas from Pennsylvania, the source of a fifth of all gas produced in the country. Because of the discovery of new shale gas reserves, its gas production grew tenfold between 2010 and 2017. Today, only Texas produces more gas than Pennsylvania.

Gas for the pipeline will come from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale, a rock formation that stretches underneath Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York; But energy infrastructure cuts through many other parts of Pennsylvania, where many residents are pushing back against pipelines.

Malinda Clatterbuck, an associate pastor at the Community Mennonite Church of Lancaster in Pennsylvania recalls getting a knock on her door back in March 2014, when a land agent arrived to survey her property, located along the route of another Williams’ pipeline project — the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline. That was the first time she had heard that she could lose the home where she had lived for nearly half a century to eminent domain.

“When you go to your kitchen and turn on that natural gas, it came from somewhere and it came at a cost,” Clatterbuck said. “The cost that’s being paid is in people’s health and in the health of the planet.”

Although the Atlantic pipeline was rerouted away from her property, Clatterbuck remained involved in the effort to help others fight against proposed projects. She helped found the organization Lancaster Against Pipelines and recently worked alongside local nuns in their ultimately unsuccessful attempt to counter the controversial Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline, which went into operation in 2018 “How you change an unjust system isn’t by looking the other direction because it doesn’t affect you, but realizing eventually it will affect you,” she said.

That’s the same message environmental advocates like Pennsylvania-raised Patrick Houston want Governor Cuomo to understand. He’s an organizer for New York City Communities for Change, part of the coalition opposing the Williams Pipeline.

“Cuomo banned fracking in New York State. Unfortunately, we still import fracked gas form our neighbors, damaging their communities, their water,” Houston said.

Rockaway residents Esther Klein, 19, and Jenn Klein, 15, head to a rally against the Williams Pipeline. Justine Calma / Grist

Back on the other end of the proposed pipeline in Queens’ Rockaway peninsula, two teenage sisters, Esther and Jenn Klein, headed to the rally last Thursday at City Hall. As they took the subway from their home in Far Rockaway bearing signs that read “stop the pipeline” and “save Rockaway,” they spoke to other passengers who approached them wanting to learn more about the pipeline.

“We don’t want bad chemicals and fossil fuels being brought to the Rockaways,” said Jenn, 15. “We have children and beaches and parks, so why should we be hurt?”

Esther, 19, chimed in, “Rockaway is our home. We’re from Rockaway, our parents, our grandparents [are too]. This is going to destroy our community.”

Pipeline or pipe dream?

So what’s next? The Williams Pipeline is currently awaiting a Water Quality Certification from New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation. The Department has until May 16 to make its decision. The DEC said it would consider whether the project met specific environmental guidelines, particularly those having to do with air and water quality. “DEC takes that role extremely seriously to prevent any deterioration of our natural resources,” it said in an emailed statement to Grist.

But even if the state ends up opposing the project, its decision may not be enough to stop the pipeline approval process. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is expected to give its approval of the project this month, having already released its final environmental impact statement for Williams’ Northeast Supply Enhancement Project. The report pretty much greenlit the project back in December, concluding that with mitigation measures, any negative environmental effects would be reduced to “less-than-significant levels.”

But advocates are not giving up, increasing pressure on state officials like Cuomo who have not yet condemned the project. To have any chance of opposing the Trump administration’s moves to fast-track pipeline approval, “states, governors, Cuomo, are going to have to back up their rhetoric with true action,” said Patrick Houston with New York Communities for Change. “People that aren’t necessarily activists, every day people are going to have to step into new territory to fight back against the fossil fuel industry.”