With President Trump preparing to nominate a ninth justice for the Supreme Court this week, tumult over the crucial vacancy is overshadowing his unprecedented potential to fill the benches of lower federal courts.

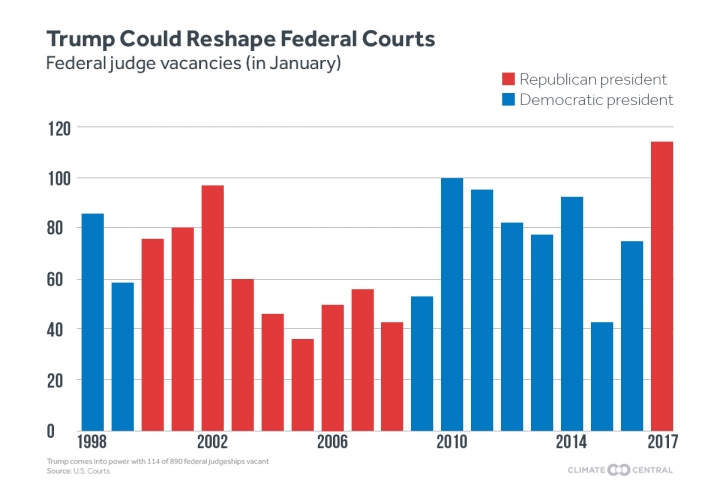

A broad refusal by Senate Republicans to approve judicial nominees during the last two years of Obama’s second term means Trump could move quickly to fill 114 vacant federal judge positions. U.S. Courts data shows that to be the most vacancies in at least 20 years.

Trump is a foe of environmental regulations who is working quickly to undo rules, programs, and agreements backed by President Obama to slow global warming. By appointing federal judges with similar views, Trump could make it harder for future administrations to secure courtroom approvals for new climate rules for decades to come.

“It’s a very serious problem,” said Glenn Sugameli, an attorney for the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife who tracks federal judge vacancies and nominations. “It does create more opportunities for bad judges to get confirmed, for bad decisions to be issued, and for courts to tilt.”

Two years ago, 43 federal judge positions were vacant. The figure has nearly tripled since then, with one out of every eight judge posts now empty as Republicans refused to hold Senate votes on the openings. That gives Trump an extraordinary opportunity to influence the slant of federal courts for decades to come.

The marquee vacancy is on the Supreme Court, and Trump said Monday he would announce his nomination of a justice to fill that spot on Tuesday. Republican senators would not consider Obama’s nomination of U.S. Circuit Judge Merrick Garland following the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, who was an ardent opponent of environmental regulations.

Three-quarters of the vacancies are on district courts. These lower courts do much of the federal judicial system’s grunt work, holding criminal and civil trials, and hearing challenges to the use of federal rules covering everything from greenhouse gas pollution to immigration.

At direct stake for the climate is the balance in how the federal justice system views federal regulations. While laws and regulations are needed to prevent corporations from wantonly polluting, such rules can reduce personal liberties.

Climate Central

Legal battles over air and water quality and climate pollution tend to boil down to a persistent debate: The fossil fuel industry promotes personal liberties over regulations, because it can be cheaper to pollute than to abide by anti-pollution rules, while environmental groups support regulations.

Some judges favor strong regulations, while others favor personal liberties. Supreme Court justices picked by Republican presidents have tended to favor personal liberties while judges chosen by Democrats tend to favor stronger regulations.

The influence of party politics in federal judge appointments continues to escalate. “Presidents have long appointed judges of their own party,” Columbia Law School professor Michael Gerrard said. “But the confirmation process wasn’t always political.”

The candidates on Trump’s list of potential picks for the Supreme Court have been backed by conservative think tanks and opposed by liberal groups.

Democrats may be able to filibuster a Supreme Court nominee, but, due to filibuster rule changes they made in 2013 to force through Obama nominees, they would have little to power to block Trump’s picks for the lower courts.F

“If many judges go on the bench who take a narrow viewing of federal agency powers under the statutes, that could have long-term consequences,” Gerrard said. “Many of these judges will stay on the bench for decades.”

Conservative think tanks, such as the Heritage Foundation, have also backed Trump’s quick moves to undermine federal environmental protections affecting fossil fuel projects. His opposition to government rules is likely to manifest in a preference for anti-regulatory federal judges.

“Trump has said that he wants to appoint a Supreme Court justice whose philosophy is similar to Scalia,” Gerrard said. “One might expect that to be not only for the Supreme Court but also for the lower courts.”

When states and environmentalists claim that plans for new or expanded oil pipelines, power plants, and chemical refineries violate federal environmental laws, it is federal judges who rule on those lawsuits.

Issues affecting everything from pollution to abortion access to gun rights come before the federal courts. It was district court judges who on Saturday froze some of the immigration restrictions that Trump had imposed one day earlier on people from seven Muslim countries.

Federal courts also hold trials for companies accused of violating clean air and other environmental laws. While the outcomes of these trials are less likely to be influenced by a judge’s regulatory bent, they can be shaped by whether the judge tends to rule in favor of prosecutors or defense attorneys.

Senate protocol dictates that both senators from a state must approve a federal judge nomination before its judiciary committee considers it. * With dozens of states being represented by at least one Democratic senator, if that custom is followed, most federal judge appointments would enjoy bipartisan support, but not all of them.

“I can only conclude that Trump’s appointments to the judiciary will be hostile to environmental regulation,” said Ann Carlson, an environmental law professor at UCLA Law.

With Trump claiming he will eliminate 75 percent of regulations, environmental groups and Democratic-led states are likely to sue the EPA to try to force it to create replacements for eliminated environmental rules.

If such cases are assigned to judges who oppose regulations, including judges nominated by Trump, the outcomes would be more likely to fall in favor of polluters, leaving the climate and environment vulnerable.

“Anti-regulatory judges could dismiss these suits, and allow an anti-regulatory EPA to run roughshod over the law,” Carlson said.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the Senate protocol associated with nominating a federal judge. Both senators from a state must approve a federal judge nomination before a committee considers it; such approval is not required earlier in the nomination process.