“Sorry about the smell; it’s not usually this bad.”

Andrew Infante is watching the rearview mirror of his Dodge RAM ProMaster and trying to maneuver out of a parking spot along a steep and congested street in downtown Seattle. In the back of the mostly empty cargo van, three bikes are roped together with a bungee cord. Two are green, with highlighter-yellow fenders like bright parentheses. The third is chalky white. That is where the smell — a murky eau de low tide — is coming from.

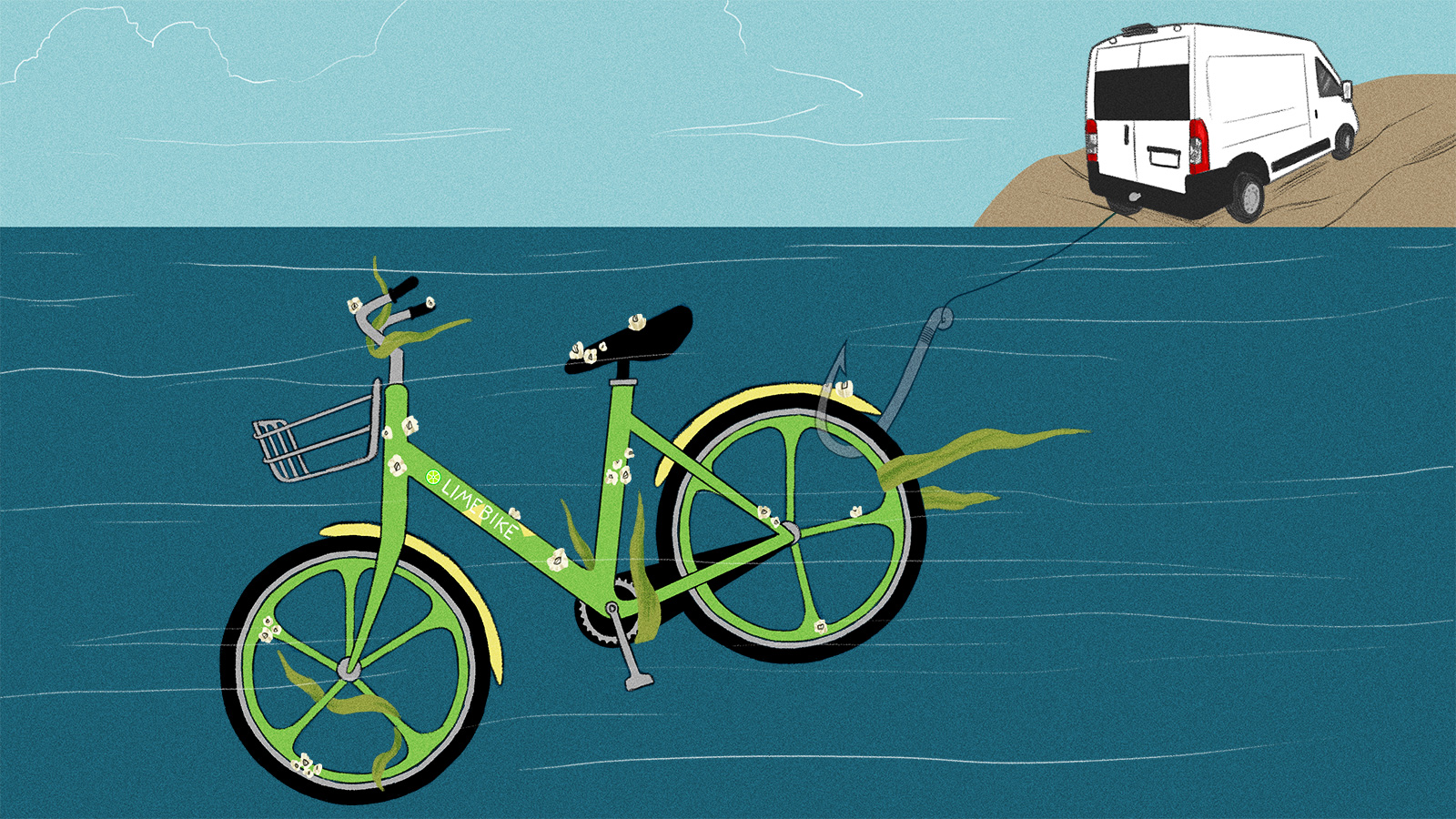

“We call them barnacle bikes,” says Infante, the Seattle operations manager for Lime, a startup that runs bike- and scooter-share programs in several American cities. “We thought we didn’t have to say, ‘Don’t throw them in the water,’ but I guess that’s not obvious to everyone.”

Fishing bikes out of lakes and waterfronts is one of many trials bikeshare companies must overcome in the Emerald City, which isn’t the easiest place to get around on two wheels. Unlike New York City or Washington, D.C., where city-sponsored bikeshare programs have flourished, the Pacific Northwest’s notorious drizzle and unrelenting topography pose challenges to the bike-curious commuter.

Seattle’s first attempt at a bikeshare, Pronto, launched in November 2014 and struggled with low ridership until the city bailed it out in February 2016. A year later, Seattle mothballed the program altogether.

“The city’s bikeshare karma was pretty bad,” says Mafara Hobson, communications director for the Seattle Department of Transportation.

But just a few months later, in July 2017, three new companies — Lime, Ofo, and Spin — lined up to join a new dockless bikeshare pilot program. Free-floating GPS-tracked bikes were scattered around the city, eschewing the expense and restrictions of docking stations. Anyone could walk up to a bike, unlock it via app, text, call, or even by paying cash at a nearby 7-Eleven, and ride exactly where they needed to go.

Initially, the bikes tended, like water, to flow downhill. The green Lime bikes, yellow Ofos, and orange Spins pooled in Seattle’s low-lying neighborhoods, crowded onto street corners and medians until unmarked maintenance vans showed up to haul them back to higher ground. But then, this February, Lime debuted an electric-assist bike capable of taking on Seattle’s most challenging terrain at a breezy 15 miles an hour.

The so-called “e-bikes” were an immediate hit. They were a little more expensive than the $1 rides on a traditional pedal bike. But you could also cover more ground with a battery boost: In 10 minutes, you could travel nearly three miles for less than a $2.75 bus fare. And the e-bikes were turning up in places Lime’s pedal bikes never did, like on the top of Queen Anne — a hill so steep that, during snows, its streets are closed to car traffic and occupied by sleds instead.

Lime started with 500 e-bikes in Seattle, but the company began adding new ones almost immediately to keep up with demand. By the end of June, there were 1,400 green e-bikes on the city’s streets; today, that number is closer to 1,600. By Lime’s count, it now operates the largest e-bike fleet in North America — and maybe the world.

Running a hubless e-bikeshare involves intricate behind-the-scenes choreography to keep charged bikes where riders want them. Lime says it is growing as fast as it can, adding new bikes and training new field operations staff to keep them running. But these maintenance-related realities add a layer of complexity to an otherwise sleek-seeming scheme.

Transportation is the top emitting sector in the United States, with nearly 2 billion tons of CO2 released into the atmosphere every year. For the more than 400 American cities who have signed a pledge of support for the Paris Climate Agreement’s goals, bikes and e-bikes offer a better way to keep urban traffic moving at a lower carbon cost. And if the partnership between municipality and startup pays off, bikeshares might redraw the urban planning of those cities.

When a gap in traffic finally appears, Infante muscles his van out of its parking spot and onto the road. On the Lime app, he selects a glowing green target that indicates a nearby bike — an e-bike with less than 10 percent of its battery power remaining. Bingo. The stoplight turns green, and we’re off to track it down.

Andrew Infante moves a Lime bike that was parked improperly on a Seattle street. Grist / Jesse Nichols

Hubless bikeshares depend on workers who search for abandoned, damaged, or out-of-the-way bikes, most often using workhorse vans like this one. It may seem incongruous that a company pioneering new forms of urban mobility is reliant on such an old one, but this is pretty standard in the industry: Maintenance crews drive around, checking that bikes are in good working order and “rebalancing them” — moving them from low-use areas to spots with higher demand, like near public bus stops or light rail stations. (Some 80 percent of Lime’s rides in Seattle start or end at transit stations, Infante says.)

Lime has a fleet of 13 vans and a team of about 50 people who take turns rebalancing the bikes around the city 24 hours a day. Now that e-bikes are in the picture, this team is also responsible for making sure they get fresh batteries when needed. This means hauling the batteries back and forth to their warehouse on the north end of the city to charge.

When demand for e-bikes is particularly high — on, say, July 4th weekend — the operations team may have trouble keeping up with all the batteries that need charging, Infante says. That can leave a lot of low-on-charge bikes sitting around. When a bike’s battery starts to run low during a ride, the Lime app will buzz to alert the rider and show the estimated mileage remaining; if the battery is critically low, a user will not be able to unlock the bike in the first place.

Infante admits that using a van for all of Lime’s maintenance isn’t practical — nor is it as sustainable as the company would like. Lime is in the early stages of experimenting with alternatives, like hauling batteries with a Prius or ferrying bikes with electric cargo trikes, which can travel in bike lanes, avoiding traffic and the bulk of a van’s carbon emissions.

The company isn’t alone in trying to find a better way to keep a fleet of e-bikes charged. Earlier this year, in an attention-getting vote of confidence that e-bikes will play an important role in future transportation, Uber acquired an e-bikeshare startup called Jump. Like Lime, Jump’s bikes are self-locking and trackable; unlike Lime, Jump skipped over pedal bikes and went straight to e-bikes, as it moved into five cities in the U.S., including San Francisco, D.C., and Austin.

In several of these cities, it installed experimental charging stations where users can choose to dock their bikes to charge in exchange for a ride credit. This brings the model closer to the classic hub bikeshares, but it’s more flexible, says Nelle Pierson, Jump’s head of communications.

Providing incentives to encourage users to take on some of the company’s logistical labor is a neat trick, and one other bikeshare companies are also considering. Lime currently offers rewards to users who unlock bikes that have stayed in one place for too long — if you move the bike, then Lime might not have to send a field technician to do the same.

A Lime operations employee unloads an e-bike to place on a Seattle street. Grist / Jesse Nichols

While it’s hard to get a handle on exactly how much energy a mass e-bike scheme requires, it’s almost certainly less than any other kind of transit. According to industry estimates, the average e-bike battery consumes between 0.4 and 0.7 kilowatt hours of power per charge, which might power the 250-watt engine for four to five days — enough to cover more than 50 miles. That means that in Seattle, Lime’s batteries may consume as much as 1,120 kilowatt hours of energy every few days. For comparison, keeping the same number of electric cars charged might take 32,000 kilowatt hours.

How much carbon is spent in generating that electricity will vary widely depending on where you are. In Seattle, much of the energy comes from hydropower, meaning its carbon intensity is relatively low. On other electrical grids that are more reliant on fossil fuels, the e-bike will have a larger footprint.

It’s been 15 minutes since Infante pulled out of the parking spot, and we’ve managed to go about half a mile. We could have walked the same distance in this time — and we still have five blocks to go to retrieve the abandoned bike. E-bikes offer a middle way between car-centric transportation and the lycra-heavy machismo of urban cycling. You can hop on an e-bike at your office, pedal it to the nearest light rail station, and catch the train home. This ease and convenience may be enough to coax some commuters out of their cars.

The average Seattle commuter spent 55 hours stuck in traffic in 2017, according to data-consulting company INRIX’s traffic scorecard. That number is likely to get worse in the coming years as major infrastructure projects shut down some of the city’s arterial routes and Seattle’s population boom puts more cars on the road.

“Cars are not going to move better in Seattle for the near future,” says Gabriel Scheer, Lime’s head of government relations. He explains that the city is going to be entering a “period of maximum constraint” soon. But even in the most crowded situations, Scheer notes, “Bikes usually get through traffic.” While pedal bikes may be a tough sell for people who don’t want to show up to work sweaty or tired, the electric assist might be the clincher.

An estimate by the National Association of City Transportation Officials found that 7,500 bikes can move through a two-way protected bike lane in an hour, compared to the 600 to 1,600 car passengers that can squeeze into the same single lane of road in the same amount of time. When a software engineer ran the numbers for New York City, he found that more than half of all trips taken during rush hour would be faster and cheaper on a bike than in a cab.

Grist / Jesse Nichols

All that might explain Uber’s investment in Jump, as well as Lyft’s move earlier this month to acquire Motivate, the largest U.S. bikeshare company, which runs NYC’s Citi Bike and D.C.’s Capital Bikeshare.

If bikeshares can get more people out of their cars and onto bikes on a regular basis, the very structure of a city could change for the greener. Seattle’s five-year Bike Master Plan has already identified almost 100 projects where bike paths and separated lanes should be installed or expanded before 2021.

The city is becoming more bike-friendly because, ultimately, it has a stake in promoting bike commuting. Seattle has allocated an estimated $65 million to build 50 miles of protected bike lanes and 65 miles of greenway trails on existing roads over the next nine years. Compare that to the $3.3 billion in estimated costs to replace the waterfront viaduct with a 2-mile-long tunnel, a project which has suffered numerous delays and mishaps over the past seven years. The tunnel is still not open for use.

Finally, Infante pulls over into a loading zone near Seattle’s packed shopping district, where tourists and office workers jostle for sidewalk space. We climb out and look for the bike, but after a few minutes, it becomes clear that it’s not there. When Infante checks the app again, the green target has disappeared. Someone has already pedaled the bike away.

This is pretty typical, Infante says. Since the e-bikes were introduced in February, demand is so high that it can be hard to find one in busy areas like this, especially when the weather is nice.

Infante says this marks another difference between Lime’s pedal bikes and its e-bikes, and another point in favor of the electric assist: He’s had people take e-bikes from his hands as he unloaded them from a van. “The e-bikes are so popular,” he says, “they tend to move themselves.”

Inspired by the people I had seen cheerfully whizzing around town on their Lime e-bikes, a few days later I decided to take one up a route I’d never attempted on two wheels before: the steep blocks that lead from Seattle’s sea-level downtown into the neighborhood called, tellingly, Capitol Hill. As I started to pedal, I was delighted to find myself flying up grades that usually leave me winded at a walk. The city seemed to open up before me, a series of vistas of expanding possibility, mobility, convenience, comfort.

The battery on Lime’s e-bikes Grist / Jesse Nichols

Then, my bike gave a sudden lurch.

All at once, my feet met the resistance of a 60-pound bike expressing a sudden gravitational preference to roll back the way I’d come — the battery was dead.

I jumped off and hauled the now-leaden bike onto the sidewalk. The Lime app had warned me a few minutes earlier that my bike was low on charge, but the mileage estimate had seemed more than adequate, until I hit the hills. Now I pushed the dead bike up the hill until I reached a flat spot where I could park it. I had never understood the phrase “learning curve” so clearly, looking ahead and behind at the hill that Lime and its riders would both have to find their way up.

Feeling foolish and a little shaken, I hailed a Lyft.