If any tough problem needs a squad of geniuses to work some magic, it’s the climate crisis. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that when the MacArthur Foundation announced the winners of this year’s so-called “genius grants” Wednesday morning, four of the 26 recipients were scientists and artists working on ways to adapt to life on our overheating planet.

The winners were selected for their creativity, talent, and accomplishments, they each receive $625,000 toward their future pursuits. Here’s a sampler of some of their work around sea-level rise, art, and agriculture.

Mel Chin, artist

Egypt, North Carolina

John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

It’s not easy to visualize environmental problems like lead-poisoned water or climate change. That’s where Chin, a conceptual artist, comes in. Last year, he installed an exhibit that envisioned Times Square drowned in 26 feet of water as a result of sea-level rise. When visitors to the exhibit aimed their phones at the sky, they saw Manhattan transformed into an ocean through an app developed with Microsoft, with more than a hundred boats hovering above them. The two-part exhibit also featured a real-life 60-foot-long sculpture of a wrecked ship, sitting in front of billboards like a beached whale.

“I think what art can provide is an option that has not been considered before,” Chin said in one of the video interviews accompanying the announcement of the prizes. “And I think that’s important, because those options may be a liberating factor that is necessary to understand how to cope with what is going around us.”

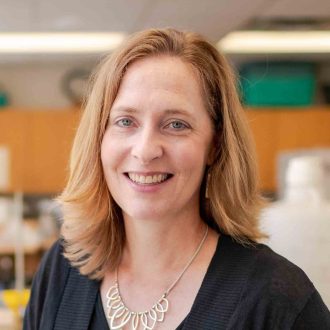

Andrea Dutton, geochemist and paleoclimatologist

Madison, Wisconsin

John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

We know the seas are already rising. The mystery is how much sea-level rise we’ll see in the future and how fast it will happen. Dutton is working to find answers by looking back 125,000 years to the last interglacial period — the last time the ocean started swallowing beaches. She collects fossils of corals that lived near the sea surface, documenting their age and elevation, to help us better predict how seas will rise in the coming years.

“I think of myself like a CSI for Planet Earth,” Dutton said. “I’m a detective collecting clues, trying to put together the puzzle of Earth’s climate history so that we can better understand its future.”

Zachary Lippman, plant biologist

Cold Spring Harbor, New York

John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Feeding the world isn’t an easy task when the population is growing, the land available for crops is shrinking, and greenhouse gases are wreaking havoc on our weather. Lippman is working to tweak plants’ genes to make them hardier and higher-yielding, so they can adapt to life in a less forgiving future. His team is domesticating the groundcherry, a (formerly) wild species that’s kin to the tomato.

“Gene editing will allow us to hopefully adapt crops to these new climate conditions to increase productivity,” Lippman said. One small step for food security, one big step for humankind.

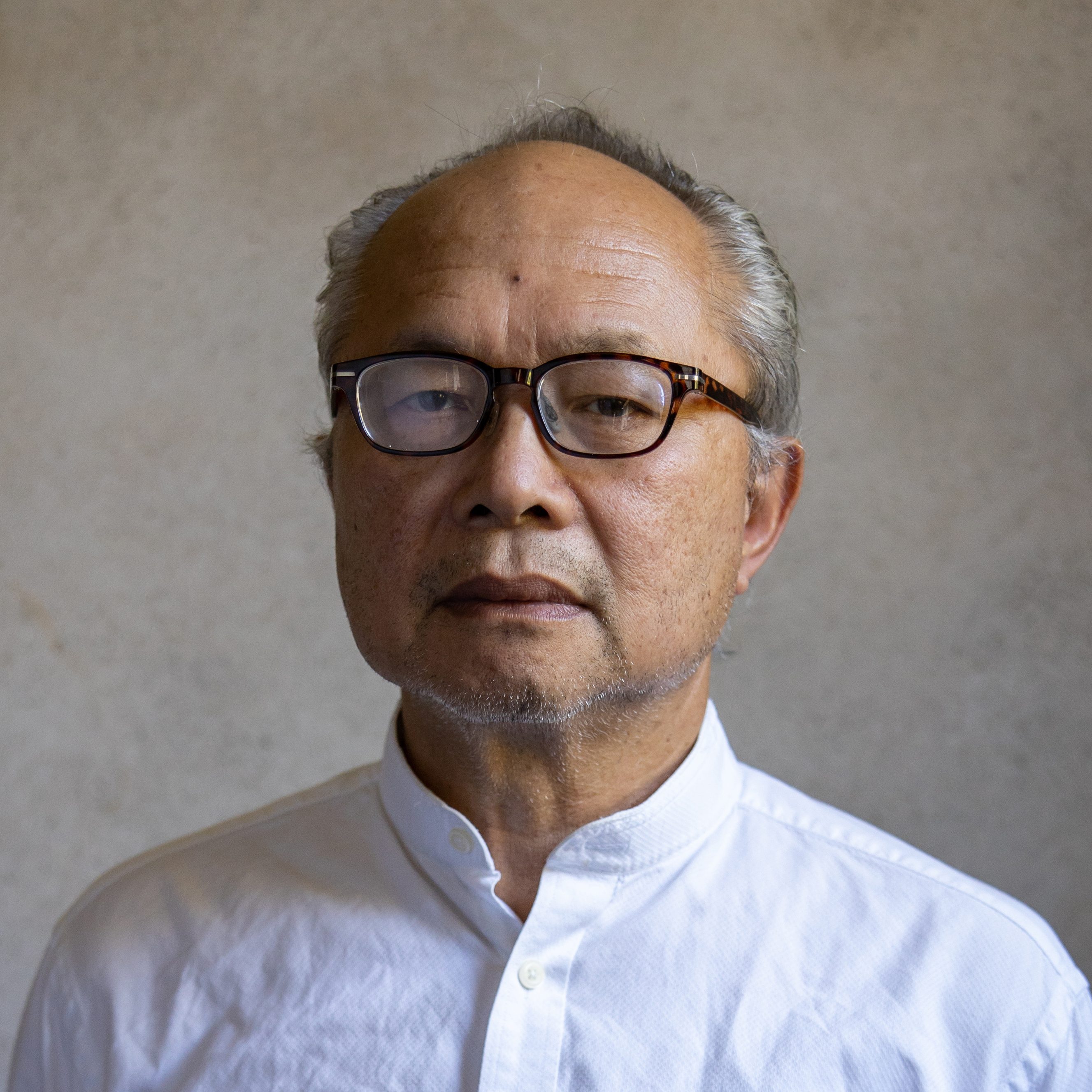

Jerry X. Mitrovica, theoretical geophysicist

Cambridge, Massachusetts

John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Mitrovica, a professor of science at Harvard, wants you to know that melting ice sheets do more than dump water into the ocean. They mess with the planet’s gravity. “Just like the sun and the moon produce a gravitational pull on the ocean, a large ice sheet also exerts a gravitational pull on the ocean,” he said. That means that as an ice sheet melts, water actually moves away from it.

Mitrovica studies geological complications like this that cause the rate of sea-level rise to vary dramatically around the world. His work showed that melting in some Antarctic regions will cause higher-than-average rise along the East Coast and in northern Europe, while melting in Greenland will affect these regions less than other places.