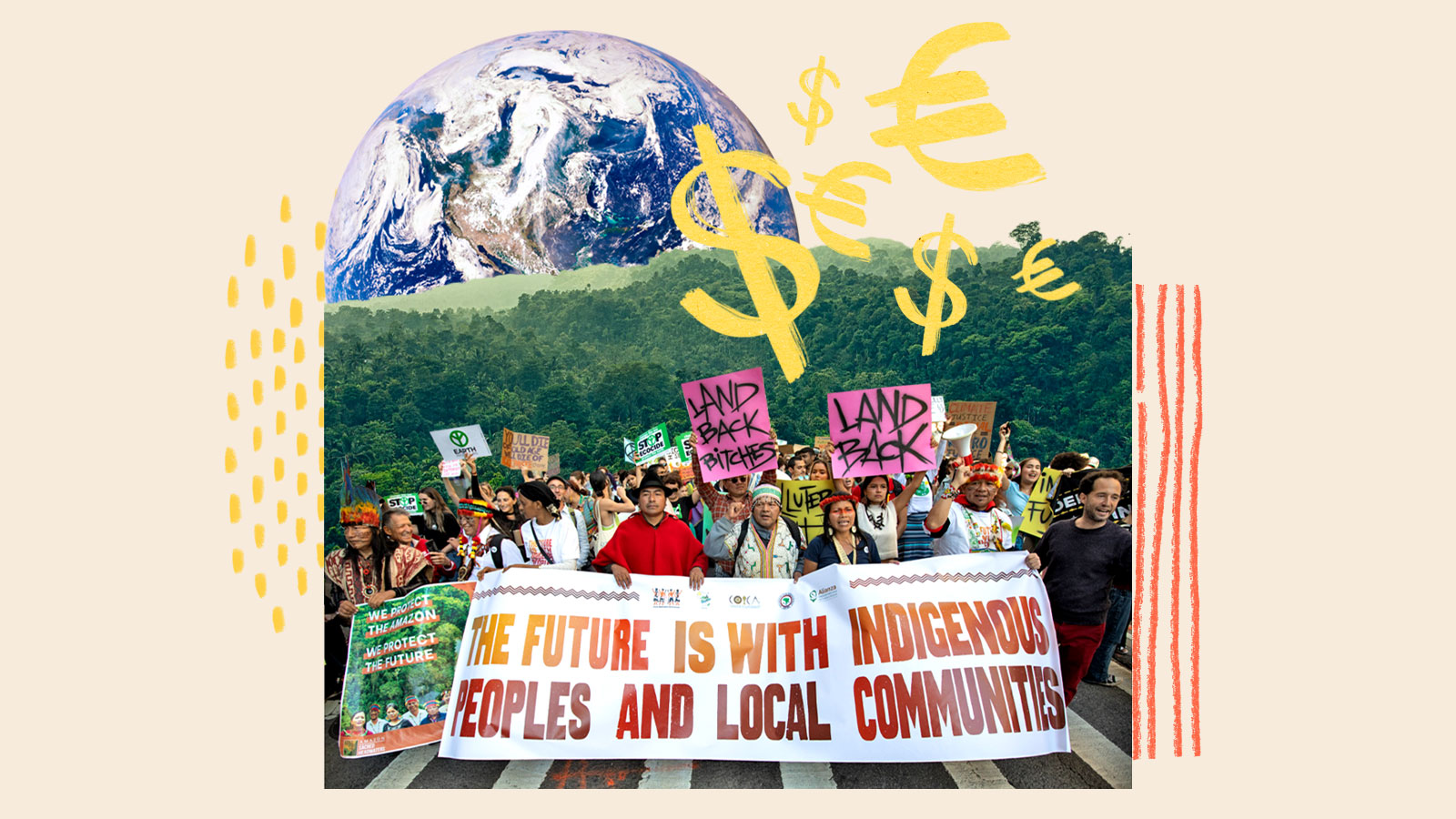

World leaders at last year’s international climate change conference COP26 pledged $1.7 billion to support Indigenous people’s efforts to protect their rights and land. Led by the United States, United Kingdom, Norway, Germany, and more than a dozen philanthropic organizations, the financing is intended to support projects like mapping traditional territories, implementing conflict resolution mechanisms, and bolstering collective governance structures. The announcement was hailed as a historic commitment that could help the world’s governments stick to the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F).

But Indigenous leaders were skeptical.

“We cannot receive this news with enthusiasm because we were not consulted in the design of this pledge,” said the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, an international Indigenous coalition, in a statement. “We suspect that many of these funds will be distributed through existing climate finance mechanisms, which have demonstrated great limitations in reaching our territories and supporting our initiatives.”

According to research by the Rights and Resources Initiative and Rainforest Foundation Norway—two nonprofit organizations dedicated to protecting forests and Indigenous rights— only 17 percent of global climate and conservation funding intended for Indigenous and local communities actually goes to projects led by Indigenous people. Indigenous women receive even less: roughly 5 percent of total world funding. The remaining money goes to larger organizations like the World Wildlife Fund and the Wildlife Conservation Society (the Wildlife Conservation Society has sub-granted funds to the Rainforest Foundation Norway to help directly support Indigenous peoples and local communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo).

Instead of waiting for the global climate and conservation funding model to change, Indigenous communities are taking action by starting local funds that support grassroots efforts, as well as larger international platforms and finance mechanisms that can raise and distribute money around the world.

Part of the problem is how isolated most donors and funding mechanisms are from local groups. In a study of $2.7 billion in global funding provided for Indigenous land tenure and forest management projects from 2011 to 2020, Rainforest Foundation Norway found that over half of the funds were disbursed by five large international organizations: the World Bank, African Development Bank, InterAmerican Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, and the United Nations Development Programme. Beyond large multilateral organizations, the next largest intermediaries were a mix of international NGOs, U.N. agencies, and consulting companies.

“There’s no point to have an intermediary if the intermediary doesn’t understand our situation,” Majo Andrade Cerda, Kichwa from Ecuador, said. “We have activated capacity now to go directly to these conversations.”

In some cases, funding goes to projects that violently displace Indigenous people. In a series of attacks between 2019 and 2021 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Kahuzi-Biega National Park, which is known for its gorilla safaris, park guards funded and trained in part by the Wildlife Conservation Society murdered at least twenty Indigenous Batwa people, group raped over fifteen women, and displaced hundreds more. In 2021, the Wildlife Conservation Society received $40 million from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’ Earth Fund for its conservation efforts in the Congo Basin.

“The money that comes does not do the exact purpose that it is meant for. It is used to militarize conservation and militarizing it in a way that it is used to evict us,” Teresa Chemosop, Ogiek of Mount Elgon, Kenya, told Grist.

When funding is distributed via international intermediaries, Indigenous groups on the ground typically miss out on funding or are given small amounts after larger organizations take cuts for everything from administrative costs to consultant salaries. Indigenous leaders say world leaders must work with them directly and provide better oversight of global funding to fix the issue.

Indigenous groups are addressing the problem by creating their own funding mechanisms. For instance, Shandia, a global financing platform for Indigenous-led projects created by the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, will support activities like coastal zone management, protection of traditional knowledge, and legal support for human rights defenders. The organization, which represents 35 million people from 24 countries, plans to launch Shandia next year. It hopes to raise and distribute $300 million from public and private funding sources over the next decade.

“It will be different because it will be totally managed by Indigenous organizations and decision making only by Indigenous peoples,” said Rukka Sombolinggi, Torajan from Sulawesi and Secretary General of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago.

Valéria Paye is Kaxuyana and the executive director of Fundo Podáali, a fund led by Indigenous women in the Brazilian Amazon. She says that her fund has had some successes, like providing support to an Indigenous women’s march last year where over 5,000 Indigenous leaders marched in Brasilia — a crucial opportunity to organize at a local level and develop connections among Indigenous groups.

Eventually, Paye hopes that Podáali will provide more support to local organizations working with Indigenous communities to protect their land, and preserve and protect culture. But to date, Paye says the fund has struggled to make the impact it wants. In the Amazon, Indigenous peoples are fighting to protect their land and lives from illegal miners, facing record deforestation, and dealing with the hostile government of President Jair Bolsonaro. To organize effectively, Podáali needs more money — money Paye says donors give to more established organizations, like the Amazon Region Protected Areas Program.

“The donors do not trust completely Indigenous peoples,” she said. “They say one thing, but in the practice and the time for action, it’s a different thing.”

Bryson Ogden, director of rights and livelihood at the Rights and Resources Initiative, believes the world is at a pivotal moment. Globally, Indigenous people are on the frontlines of drought, storms, and heatwaves. Indigenous peoples have been recognized as the best stewards of land, but the challenge is ensuring that they have the funds and support they need to protect their rights and achieve biodiversity goals. “It’s important that we take advantage of this momentum,” Ogden said. “More equitable partnerships have to be there if these ambitions are to be realized.”

Sombolinggi added that better partnerships would require donors to change their capacity requirements for recipients. For many donors, Sombolinggi said, capacity means “the capacity to speak the language of colonizers.” In other words, Indigenous organizations are judged on their ability to produce receipts and write proposals in English, rather than the impact their organizing efforts have in their own communities.

Another issue is that some countries do not recognize Indigenous groups, which means they may not be eligible for funding that requires an Indigenous group to have some form of state-recognition or designation. Torbjørn Gjefsen, climate policy adviser at Rainforest Foundation Norway, said that the global model needs to adapt to Indigenous peoples, rather than the other way around. “We’re not calling for [Indigenous peoples] to become NGOs,” he said. “They need to be allowed to do this in a way that’s in compliance with their rights and their way of living.”

Teresa Chemosop, Ogiek of Mount Elgon, Kenya, works with the Chepkitale Indigenous People Development Project to organize assemblies of Indigenous women from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania that advocate for Indigenous women to be included in international conversations. Indigenous women receive less than a third of the global funds that end up with Indigenous-led projects and, according to Chemosop, are less frequently invited to Africa-wide or international meetings.

“We just don’t want to still continue having this stereotype that it’s only men who can champion our rights,” she said. “We believe the women are the backbone of our communities and that is why we need to empower them.”

Chemosop added that Indigenous women in Africa have the kind of skills, experiences, and responsibilities that often don’t translate to a traditional funding application. They often speak multiple languages fluently, but cannot read or write. They are culture bearers and leaders, but may not have reliable internet access. According to a 2020 report from the International Indigenous Women’s Forum, less than 1 percent of Indigenous women in Africa have advanced education. “They’ve always made it very difficult to access these funds, so some of us give up, and of course because we don’t understand the process itself, we end up not getting the funds,” Chemosop said.

Lack of access to funding is a direct obstacle to the work Chemosop is doing with Indigenous women in East Africa. Before the first ever African Protected Areas Congress, a continent-wide conference to discuss conservation, Chemosop helped organize Indigenous communities to write a declaration that called on the conference to protect Indigenous land, women, and rights.

One of the main concerns raised by the declaration’s authors was the impact of so-called fortress conservation on Indigenous communities. Fortress conservation, a global practice that insulates nature from human contact to preserve biodiversity, often means displacing and even murdering Indigenous people to achieve conservation goals. Many large international organizations, like the World Wildlife Fund, receive funding to protect nature — and, in theory, Indigenous people — but instead engage in fortress conservation. In a recent report that examined ten case studies of violent fortress conservation, the World Wildlife Fund was named in eight.

The declaration called on the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which organized the African Protected Areas Conference, to set up a commission on decolonizing conservation and work with states and other parties to pass laws that end fortress conservation practices. “The end of colonialism was meant to be the end of powerful outsiders taking control of resources and using these to expand their control yet further,” the declaration reads. “We call for the end of the colonial curse and the fulfilment of the de-colonial promise.”

The document was a unique rallying cry for Indigenous people in East Africa ahead of the historic conference, but Chemosop said that limited funds prevented some Indigenous women from participating in the process because they couldn’t afford to travel to the assembly where the declaration was written.

At Shandia’s launch in New York City during last month’s climate week, the Christensen Fund, a private foundation that was part of the $1.7 billion COP26 pledge, announced five years of support for the platform. Now, the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities hopes that COP27, which will take place in Egypt in November, will be an opportunity to build on that momentum.

“It’s really the rights of the community organizations to decide what they want to do,” Sombolinggi said.

This story has been updated to clarify the timing of the Bezos Earth Fund in the Congo Basin and to include information from the Wildlife Conservation Society.