The record-breaking flooding disaster in the Midwest is just beginning.

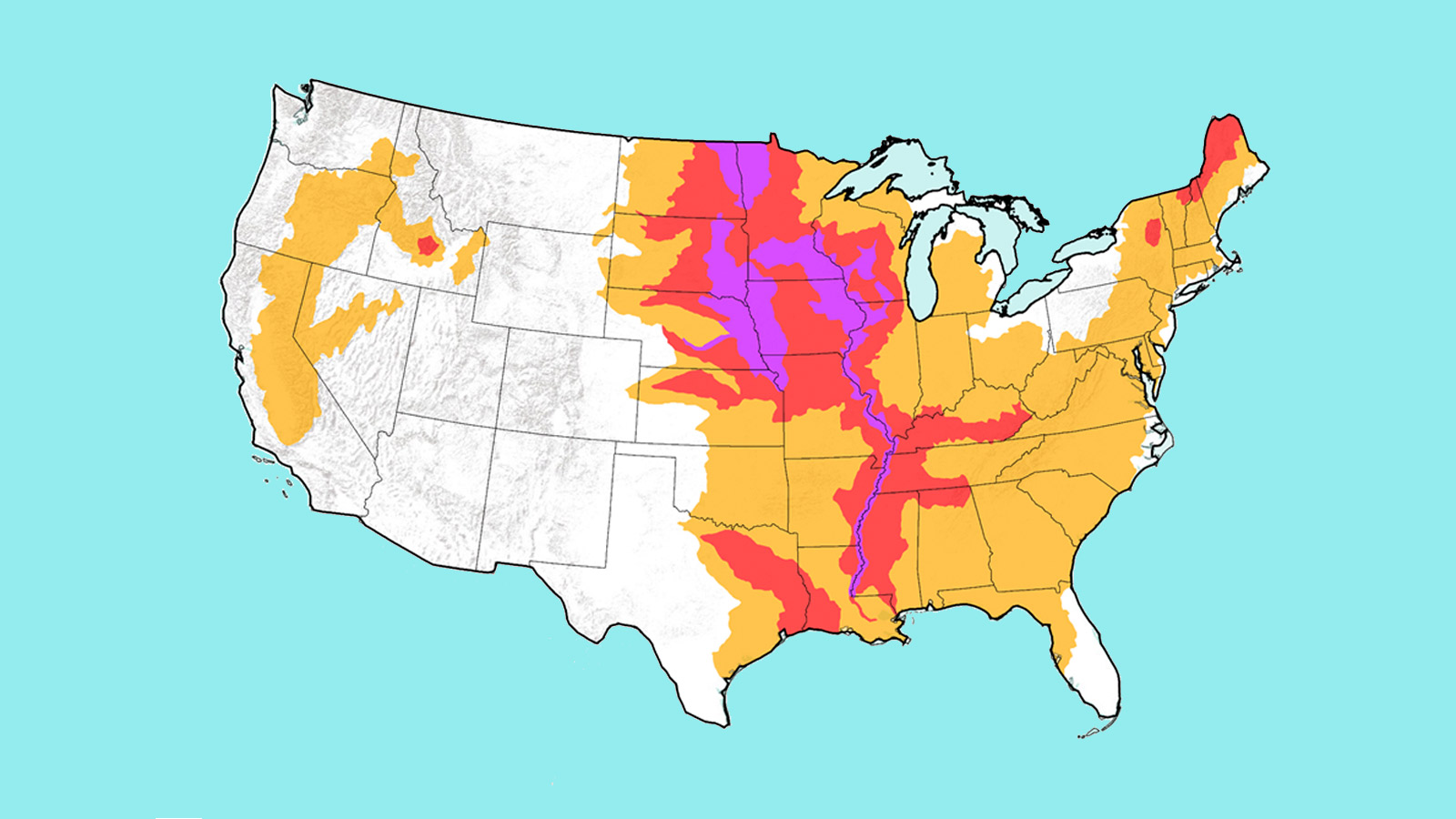

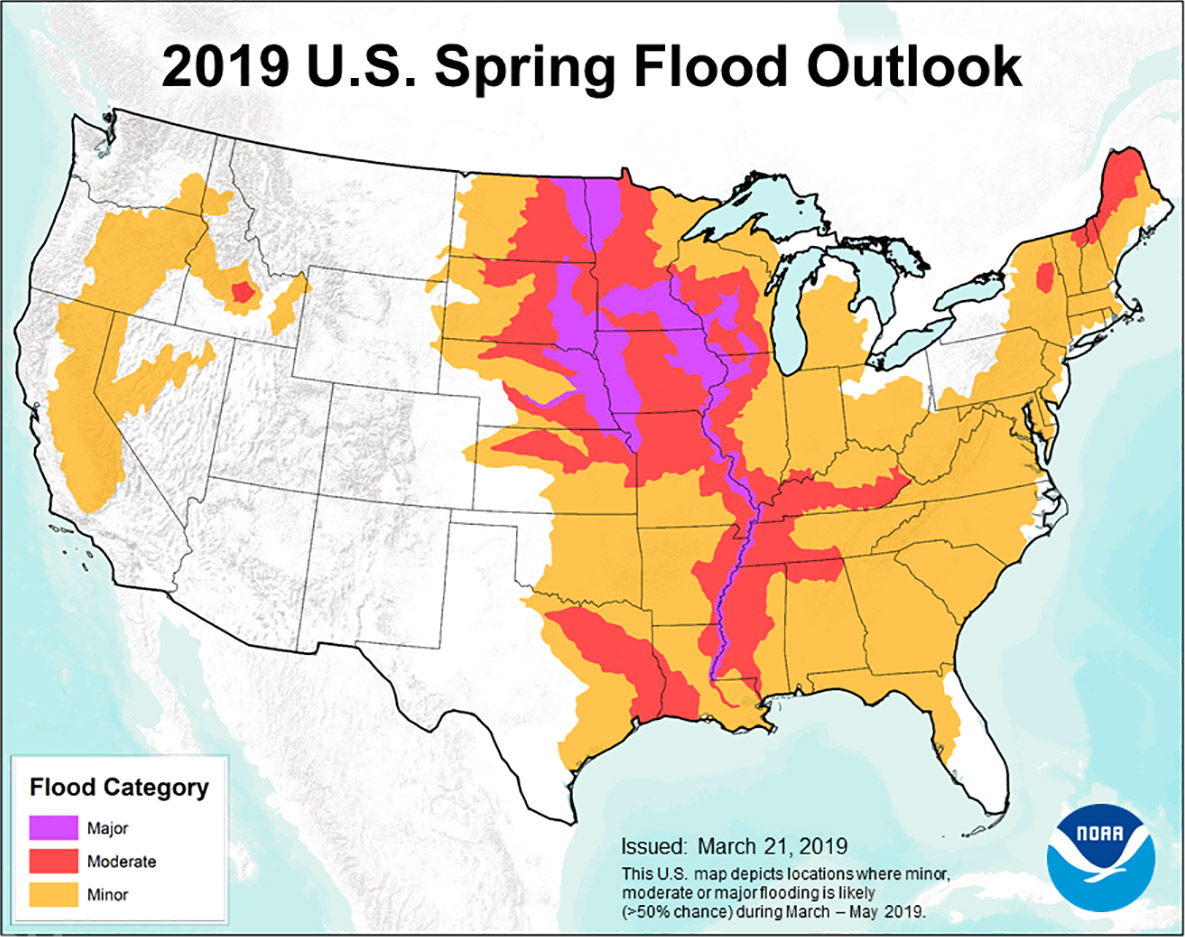

On Thursday, the National Weather Service issued its annual spring flood outlook, and it is downright biblical. By the end of May, parts of 25 states — nearly two-thirds of the country — could see flooding severe enough to cause damage.

Pretty much every major body of water east of the Rockies is at elevated risk of flooding in the coming months, including the Mississippi, the Red River of the North, the Great Lakes, the eastern Missouri River, the lower Ohio, the lower Cumberland, and the Tennessee River basins.

NOAA

“This is shaping up to be a potentially unprecedented flood season, with more than 200 million people at risk for flooding in their communities,” said Ed Clark, director of NOAA’s National Water Center, in a press release. That represents about 60 percent of all Americans.

Across the Midwest, the recent floods have already caused an estimated $3 billion in damages — a total that will surely rise. Extremely heavy snowfall in the upper Midwest this winter, combined with a forecast for a wetter-than-normal spring, set the stage for this calamity. With the exception of Florida and New England, soil moisture in much of the eastern United States is above the 99th percentile — literally off the charts. When the ground is this saturated, there’s nowhere for water to go but into streams and rivers, taking precious topsoil with it and carving lasting changes into the land.

And that’s exactly what’s been happening in Nebraska, where flood-protection infrastructure has been utterly overwhelmed by record-setting water levels. Virtually every levee on the Missouri River between Omaha and Kansas City has been breached in the last week. “I don’t think there’s ever been a disaster this widespread in Nebraska,” said Governor Pete Ricketts.

Several states and tribal nations throughout the region have declared a state of emergency. President Trump has approved a federal disaster declaration for Nebraska, and one is pending for Iowa. In a tweet showing an aerial video of the flooding, the Nebraska State Patrol wrote: “The Missouri looks like an ocean.”

None of this is supposed to be under water.

Here's what the Missouri River looks like just across from Nebraska City into Iowa. If you ever drive to Kansas City, you're probably familiar with this interchange of I-29 and Highway 2. The Missouri looks like an ocean.#NSP575 pic.twitter.com/kwkkAs5fha

— Nebraska State Patrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 21, 2019

The flooding can’t be considered without the ongoing effects of climate change. Since a warmer atmosphere can retain more water vapor, extreme precipitation is becoming more frequent and more intense. Rainfall in the eastern U.S. is now between 29 and 55 percent heavier than it was 60 years ago, depending on the region.

Ironically, U.S. efforts to control flooding have mostly served to make things worse. Over the past hundred years, we’ve built levees to transform free-flowing rivers into pathways for shipping and commerce — straightening their routes to allow for easier and more predictable navigation. And the illusion of flood control has led to development in historically risky flood plains, adding to the potential for catastrophe. In the context of climate change, a complete rethink of floodplain development in the United States can’t happen soon enough.