This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

During his State of the Union address Tuesday night, President Barack Obama reiterated his call to eliminate federal subsidies for fossil fuels in an effort to speed up the transition to cleaner energy sources. It’s something he’s asked for nearly every year of his presidency, and it hasn’t happened yet. But this year, he added something new: a plan to charge oil and coal companies more for leases on federal land, to offset the damage their products do to the climate.

It was just the latest piece of bad news for the coal industry, which is the nation’s No. 1 source of greenhouse gas emissions. Everywhere you look, there are signs that 2016 is shaping up to be one of the worst years coal has had in recent memory.

The onslaught started at the end of December, when China announced plans to close 1,000 coal mines as part of its campaign to reduce crippling air pollution and the world’s highest greenhouse gas emissions. China also plans to reduce its share of electricity production from coal to 62.6 percent by next year, down from 64 percent now, according to Bloomberg. That’s great news for Chinese citizens, who have recently been subjected to air pollution up to 40 times higher than what the World Health Organization considers safe. But it’s a big letdown for coal producers in the United States, who have been increasingly desperate for new foreign markets for their product; coal demand in the U.S. has dropped 10 percent just in the last three years. The assumption that China’s seemingly insatiable growth is a safe long-term bet for coal is vanishing — in fact, the latest official estimate is that Chinese coal consumption already peaked back in 2013.

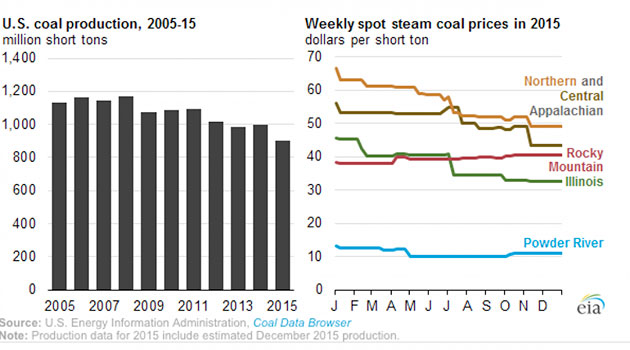

As domestic and foreign demand dip, U.S. coal production has also crashed to a 30-year low, according to federal data released this week. It’s the latest low point of a trend that has been heading downhill since Obama took office:

EIA

That trend is being driven somewhat by electricity companies’ anxiety about the Clean Power Plan, Obama’s new rules to limit emissions from power plants. But even more importantly, coal is getting hammered by competition from cheap natural gas. Since Obama took office, natural gas production in the U.S. has jumped 20 percent, and prices have correspondingly fallen to record lows. As a result, the obvious choice for utilities is to burn natural gas instead of coal. And despite protestations from Republican legislators, coal country seems to be preparing for the fact that its historic lifeblood isn’t coming back anytime soon. An editorial in this week’s Lexington Herald-Leader argued that “no one should expect a revival of Eastern Kentucky coal jobs when not even Kentucky’s electric utilities can afford to buy the region’s coal.”

All of this is devastating for coal companies’ bottom lines. One recent study found that in the last five years, U.S. coal producers have lost 76 percent of their value. The latest casualty is Arch Coal, the country’s second-largest coal company, which filed for bankruptcy on Monday in the hopes of eliminating more than $4.5 billion in debt. As ThinkProgress reported, “in early 2011, stock in Arch Coal peaked at $260 a share — on Monday, shares in Arch Coal were worth less than a dollar.”

Coal’s future doesn’t seem much brighter. More than two dozen coal-reliant states are suing the Obama administration over its climate plan. But most of those same states are simultaneously planning to comply with the plan — not exactly a sign that they see a coal renaissance around the corner. And the global climate pact reached in Paris in December was a clear signal that clean energy is on the rise.

With all that said, coal isn’t quite out of the game yet. Even with Obama’s climate plan, the U.S. is on track to get 26 percent of its power from coal in 2040. And we’re still a ways off from being on track to meet the ambitious global warming limit agreed to in Paris. But the year is young — there’s plenty of time for coal’s prospects to get even worse.