The world’s biggest petroleum exporter, a country built with oil money, and a founding member of the most powerful oil cartel on Earth, is now styling itself as a pioneer of climate change solutions.

At the United Nations climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt last week, Saudi Arabia held a separate meeting for Middle East and North African countries to go over the details of two separate initiatives aimed at cutting emissions and fighting desertification. The plans include planting 50 billion trees around the region, expanding wind and solar power, and enhancing carbon capture and storage technologies.

What’s not included is any mention of cutting oil production. In fact, the state-run oil company Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitter as well as the world’s most valuable company, said that it’s aiming to raise its production capacity by 2025, even as it plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible by 2050.

Saudi Arabia, in other words, wants to remain an oil power and somehow go green at the same time.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, de facto leader of the absolute monarchy, sees no contradiction in this, sources told Grist. Taking measures to combat climate change will ensure that Saudi Arabia both diversifies its economy and remains one of the world’s political power brokers, a position it gained as a direct result of its rich petroleum reserves. Selling more oil, Saudi officials have reasoned, can help facilitate this balancing act. And as fuel prices remain high following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, experts said that the Saudi government is doing what any oil-producing country would do: meeting demand.

“Saudi Arabia knows that its oil will be the last oil purchased and produced in the world,” said Ellen Wald, a historian and scholar of the energy industry, in an email. This, she explained, is because Aramco has by far the lowest cost of production on the planet, at around $2.80 per barrel, thanks to its vast reserves conveniently pooling near the desert’s surface. “So even if every car on the road is an EV [electric vehicle] and all the planes run on batteries, anyone still buying and using oil will be buying Saudi oil.”

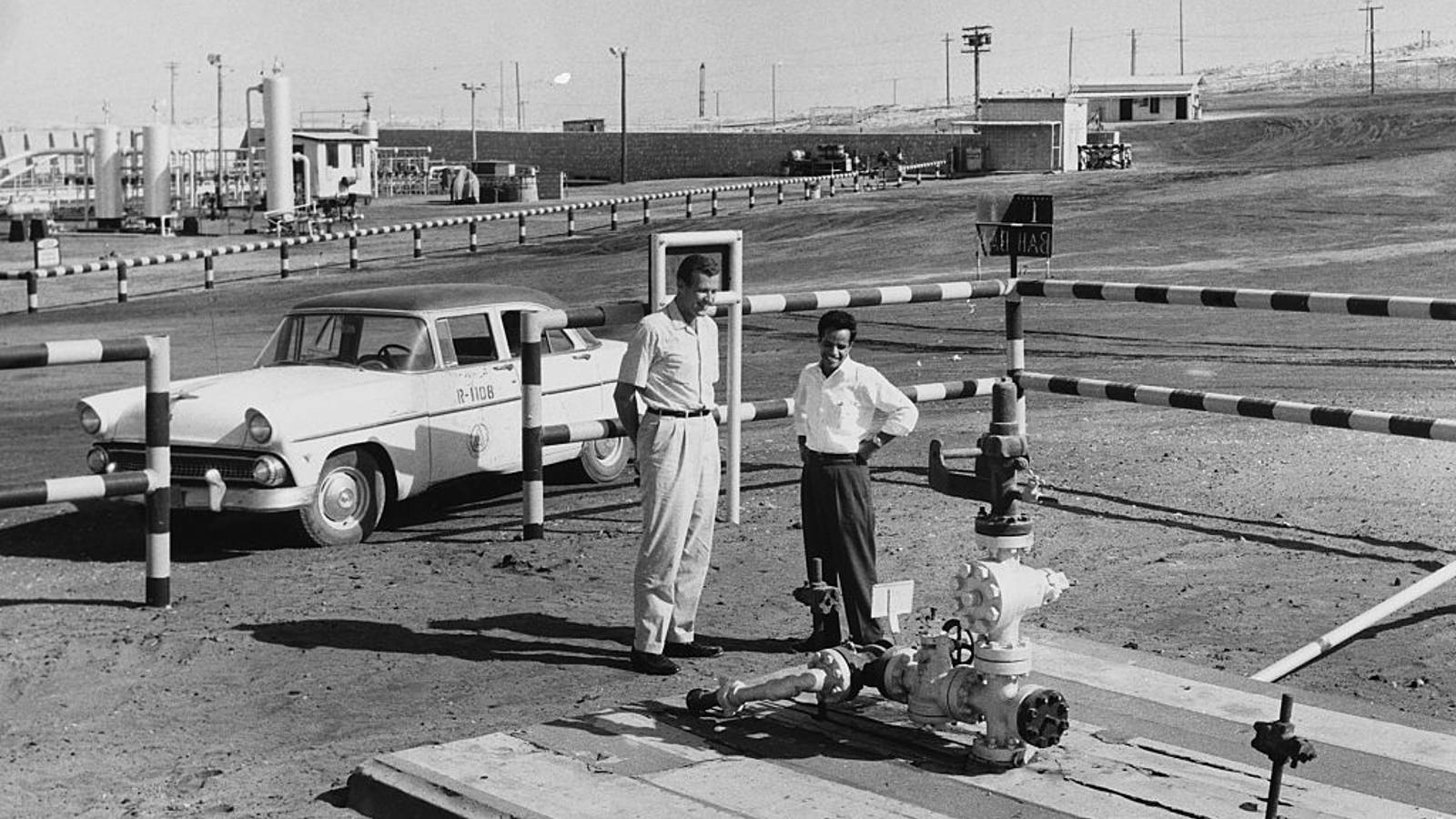

The discovery of oil radically transformed Saudi Arabia over the course of the 20th century, turning a largely nomadic desert society into a country with sprawling cities and a highly educated workforce. After an American oil company struck liquid gold in Dhahran in 1938, tapping into what would become the largest source of petroleum in the world, the kingdom was rapidly outfitted with pipelines, refineries, and export terminals. Aramco, as the oil venture came to be called, was owned by Texaco and other American oil companies until the Saudi government bought them out in 1980. With its vast oil wealth fully under the control of the ruling family, the House of Saud, the country deepened its ties with the West and secured a powerful spot at the geopolitical table. It’s one they intend to hold onto.

When scientists began sounding the alarm about climate change in the early 2000s, Saudi Arabia took up a reactionary position at the United Nations, highlighting skeptical views on the science of global warming and attempting to block climate policy. The kingdom’s tone began to change, however, after the 2015 Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty with the goal of limiting global temperature increases to well below 2 degrees celsius compared to pre-industrial levels.

“After Paris, there was no turning back – the world will decarbonize,” said Karim Elgendy, an urban sustainability and climate consultant at Chatham House, a London-based policy institute. Saudi Arabia “realized that being at the table is better than not being at the table. Shaping the outcome is better than being affected by the outcome.”

The following year, the kingdom launched “Vision 2030,” a policy framework meant to diversify the economy and reduce reliance on oil revenues, which have historically accounted for more than 60 percent of the country’s economy. One of its major goals was buffing up tourism. The government also loosened its restrictions on women, allowing them to drive without a male guardian and enter public spaces without headscarves. In 2020, the government announced that Saudi Arabia will go “net zero” within 40 years, a term that refers to balancing the amount of emissions released and the amount of carbon removed from the atmosphere. It will be no easy feat.

Saudi Arabia’s rapid modernization saw the rise of towering skyscrapers, luxury malls, and a proliferation of private cars, along with a new way of life for its 35 million residents. As it developed, the country’s carbon footprint mushroomed until by 2017, Saudi Arabia was the fifth largest oil consumer in the world after the United States, China, India, and Japan. A sizable share of its emissions comes from energy consumption during the country’s punishingly hot summers, when temperatures frequently top 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Another significant portion comes from the operations of the state-run oil company Saudi Aramco, which experts estimate has generated more than 4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions since 1965.

Despite this, the Saudi government has repeatedly dodged responsibility for contributing to climate change, claiming that it’s a developing nation like Jordan or Ghana. Officials have refused to join other global superpowers at the UN climate summit that are pledging funds for “loss and damage” financing to poorer countries hit hard by climate change.

Earlier this year, Aramco announced that it would be net-zero by 2050. This target is “a big deal because of the impact [it] could potentially have,” said Maeve O’Connor, an analyst at the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a London-based think tank that carries out analysis on the market impacts of the energy transition. “They emit as much as some medium sized countries.”

But O’Connor characterized Aramco’s net-zero plans as “heavy on rhetoric and light on substance.” Rather than cutting emissions in absolute terms, for instance, the company plans to measure its progress using carbon intensity, a ratio of the amount of carbon dioxide released for every unit of energy produced. That would allow Aramco to claim success if it increases oil production while keeping its emissions the same.

The company believes that it can do this by capturing and reusing the carbon dioxide emitted during oil production, rather than allowing it to enter the atmosphere. Successfully doing so relies on the nascent carbon capture and storage industry. Last week at the UN climate summit, Aramco announced plans for a new carbon capture and storage hub, which it said will be able to store 9 million tons of carbon a year by 2027.

That captured carbon would then be injected back into wells to extract even more petroleum. While Aramco has promoted this as a sustainable method of keeping carbon beneath the earth, O’Connor said that the additional oil reaped from the practice will eventually end up combusting in someone’s vehicle or power plant in another part of the world – causing a net increase in emissions. (Saudi Aramco declined a request for comment.)

The Saudi government has argued that other countries’ emissions, even if a result of Aramco’s oil, are not its problem. Officials have said that the government wants to take a “comprehensive” approach to tackling climate change, which includes using oil revenues to fund its green initiatives.

These programs include some conventional climate-friendly efforts such as new solar and wind-power farms and an update of existing building standards to promote energy efficiency. But they also include ostentatious developments such as NEOM, a “smart city” with blueprints resembling mockups of a science fiction video game, complete with classrooms taught by holograms, flying elevators, and an urban spaceport.

The brainchild of Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman, NEOM has been under construction in the country’s northwestern desert since 2019 and is scheduled to be completed by 2025. The city is expected to run on a combination of wind and solar power and be a hub for green hydrogen, a fuel created when electrolyzers powered by renewable energy extract hydrogen from water molecules. (The Saudi government has said it aims to become the world’s top exporter of green hydrogen in the next half century.) The project has been plagued by setbacks, including violent confrontations with members of the indigenous Howeitat tribe who are being forcibly displaced by the project’s construction.

NEOM is the latest in a string of “smart cities” that have proliferated across the Middle East in the past two decades, from Abu Dhabi’s failed Masdar City to Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s new administrative capital in the middle of the desert. Gokce Gunel, an anthropology professor at Rice University who has written extensively about clean energy in the Arab Gulf states, said that projects like NEOM are primarily ways for ruling families in the region to maintain their standing.

“There’s a political function to these projects even if they don’t fulfill their promise,” Gunel said. She calls them “status quo utopias”. Enterprises like NEOM “claim to create utopias but they really want to preserve the present the way it is, to maintain the way oil has made the world.”

Elgendy, who is on contract with the Saudi government to work on the city and cannot discuss its details due to a nondisclosure agreement, sees it differently. To him, NEOM is another example of the Saudi government’s determination to stay relevant in a post-oil world, an indication of its desire to “stay at the geopolitical table.”

“Instead of dragging their feet and slowing down the process, they have tried to buy a little bit of time,” Elgendy said. The kingdom’s climate action proposals let them “steer the process in a way that allows them to use oil and gas revenues to diversify their economy and become something else, become a different Saudi Arabia.”

But in the long term, it could be hard to keep up a balancing act that depends on the rest of the world’s response to climate change. When the fallout from the war in Ukraine inevitably dies down, governments will have to make tough choices about how and when to shift their economies away from fossil fuels. If major emitters like the United States make progress quickly, Saudi Arabia’s endeavors could become more difficult to pull off, even as other countries continue to buy oil.

And someone will be buying oil. Petroleum-derived products are ubiquitous in modern society, from synthetic clothing fibers to shampoos and detergents to plastic airplane parts. But the petrochemical industry that produces these products accounts for only about 17 percent of global demand for oil. O’Connor said that no matter how much the world wants petrochemicals, as grids shift to renewable power and electric cars become more popular, Saudi Arabia will see its oil revenues shrink. She pointed to the most recent report from the International Energy Agency, which found that starting in the mid-2020s, fossil fuel demand will decrease each year by an average amount roughly equivalent to the lifetime output of a large oil field.

“It’s a very fair point that once the demand is there someone is going to fill it, but what we would say is that that demand is beginning to wane and it will wane severely,” O’Connor said. “There’s a seismic shift about to take place in energy demand towards more sustainable sources. Aramco and Saudi Arabia need to reckon with that.”