Leadership in addressing climate change in the United States has shifted away from Washington, D.C. Cities across the country are organizing, networking, and sharing resources to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and tackle related challenges ranging from air pollution to heat island effects.

But group photos at climate change summits typically feature big-city Democratic mayors rubbing shoulders. Republicans are rarer, with a few notable exceptions, such as Kevin Faulconer of San Diego and James Brainard of Carmel, Indiana.

Faulconer co-chairs the Sierra Club’s Mayors for 100 Percent Clean Energy Initiative, which rallies mayors around a shared commitment to power their cities entirely with clean and renewable energy. Brainard is a longtime champion of the issue within the U.S. Conference of Mayors and the Climate Mayors network.

In our research at the Boston University Initiative on Cities, we found that large-city Republican mayors shy away from climate network memberships and their associated framing of the problem. But in many cases they advocate locally for policies that help advance climate goals for other reasons, such as fiscal responsibility and public health. In short, the United States is making progress on this issue in some surprising places.

Climate network members are mainly Democrats

In our initiative’s recent report, “Cities Joining Ranks,” we systematically reviewed which U.S. cities belong to 10 prominent city climate networks. These networks, often founded by mayors themselves, provide platforms to exchange information, advocate for urban priorities and strengthen city goverments’ technical capacities.

The networks we assessed included Climate Mayors; We Are Still In, which represents organizations that continue to support action to meet the targets in the Paris climate agreement; and ICLEI USA.

We found a clear partisan divide between Republican and Democrat mayors. On average, Republican-led cities with more than 75,000 residents belong to less than one climate network. In contrast, cities with Democratic mayors belonged to an average of four networks. Among the 100 largest U.S. cities, of which 29 have Republican mayors and 63 have Democrats, Democrat-led cities are more than four times more likely to belong to at least one climate network.

This split has implications for city-level climate action. Joining these networks sends a very public signal to constituents about the importance of safeguarding the environment, transitioning to cleaner forms of energy, and addressing climate change. Some networks require cities to plan for or implement specific greenhouse gas reduction targets and report on their progress, which means that mayors can be held accountable.

Constituents in Republican-led cities support climate policies

Cities can also reduce their carbon footprints and stay under the radar — a strategy that is popular with Republican mayors. Taking the findings of the “Cities Joining Ranks” report as a starting point, I explored support for climate policies in Republican-led cities and the level of ambition and transparency in their climate plans.

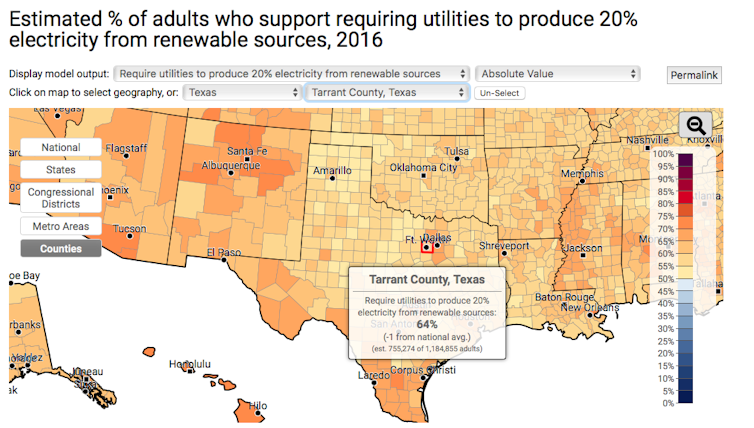

To tackle these questions, I cross-referenced Republican-led cities with data from the Yale Climate Opinion maps, which provide insight into county-level support for four climate policies:

- Regulating carbon dioxide as a pollutant

- Imposing strict carbon dioxide emission limits on existing coal-fired power plants

- Funding research into renewable energy sources

- Requiring utilities to produce 20 percent of their electricity from renewable sources

In all of the 10 largest U.S. cities that have Republican mayors and also voted Republican in the 2008 presidential election, county-level polling data showed majority support for all four climate policies. Examples included Jacksonville, Florida, and Fort Worth, Texas. None of these cities participated in any of the 10 climate networks that we reviewed in our report.

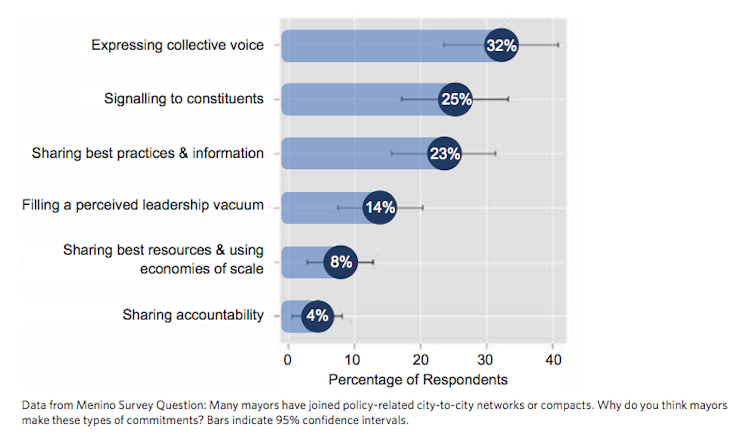

This finding suggests that popular support exists for action on climate change, and that residents of these cities who advocate acting could lobby their elected officials to join climate networks. Indeed, we have found that one of the top three reasons mayors join city policy networks is because it signals their priorities. A mayor of a medium-sized West Coast city told us: “Your constituents are expecting you to represent them, so we are trying politically to be their voice.”

Climate-friendly strategies, but few emissions targets

Next, I reviewed planning documents from the 29 largest U.S. cities that are led by Republican mayors. Among this group, 15 have developed or are developing concrete goals that guide their efforts to improve local environmental quality. Many of these actions reduce cities’ carbon footprints, although they are not primarily framed that way.

Rather, these cities most frequently cast targets for achieving energy savings and curbing local air pollution as part of their master plans. Some package them as part of dedicated sustainability strategies.

These agendas often evoke images of disrupted ecosystems that need to be conserved, or that endanger human health and quality of life. Some also spotlight cost savings from designing infrastructure to cope with more extreme weather events.

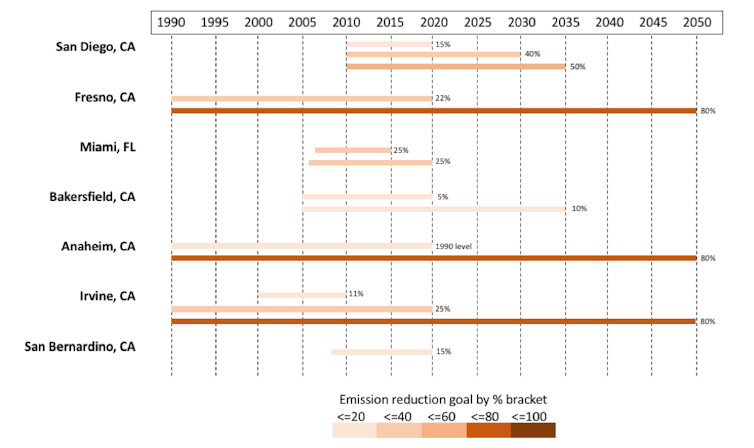

In contrast, only seven cities in this group had developed quantitative greenhouse gas reduction targets. Except for Miami, all of them are in California, which requires its cities to align their greenhouse gas reduction targets with state plans. From planning documents, it appears that none of the six Californian cities goes far beyond minimum mandated emission reductions set by the state for 2020.

Watch what they do, not what they say

The real measure of Republican mayors taking action on climate change is not the number of networks they join but the policy steps they take, often quietly, at home. While few Republican mayors may attend the next round of subnational climate summits, many have set out policy agendas that mitigate climate change, without calling a lot of attention to it — much like a number of rural U.S. communities. Focusing narrowly on policy labels and public commitments by mayors fails to capture the various forms of local climate action, especially in GOP-led cities.

Carmel, Indiana Mayor James Brainard has suggested that some of his less-outspoken counterparts may fear a backlash from conservative opinion-makers. “There is a lot of Republicans out there that think like I do. They have been intimidated, to some extent, by the Tea Party and the conservative talk show hosts,” Brainard has said.

![]() Indeed, studies show that the news environment has become increasingly polarized around accepting or denying climate science. Avoiding explicit mention of climate change is enabling a sizable number of big-city GOP mayors to pursue policies that advance climate goals.

Indeed, studies show that the news environment has become increasingly polarized around accepting or denying climate science. Avoiding explicit mention of climate change is enabling a sizable number of big-city GOP mayors to pursue policies that advance climate goals.