Raj Patel has worked for both the WTO and World Bank, and is currently active in campaigns against them. He is based in Ithaca, N.Y., where he is a Ph.D. student at Cornell University and a co-editor of the Voice of the Turtle.

Monday, 29 Nov 1999

SEATTLE, Wash.

Seattle is a beautiful city, nestled on the edge of Puget Sound, with the Pacific stretched beyond, and bordered by the Cascade and Olympic mountains, which rise majestically over the city’s broad horizons. Or at least that’s what they say. When I got here, though, it was hard to see anything more than 20 feet away due to driving rain. The guidebook forgot to mention that Seattle’s three most important monopolies are operating systems, commercial aircraft, and precipitation.

What I could see, though, was very pleasing. As I arrived at my Seattle hosts’ house, I passed a 20-foot-tall statue of Lenin parked by the roadside. Rescued from Eastern Europe after 1989, the statue is one of very few to show Lenin against a background of guns and flames, without a book in his hand. The symbolism stresses the fact that Lenin was not just a man of words, but one of action. In Lenin’s hand, someone has placed a banner saying, “End Corporate Rule — WTO — Who’s Taking Over?” Surely an auspicious start to the week.

I am not alone in having made the pilgrimage to Seattle. People say that more than 50,000 have arrived and will be out on the streets over the next few days. And all because of three little words: “World Trade Organization.” The WTO is actually quite a small bureaucracy; it has only 500 employees and a modest budget, but it has in the past three years come to represent and promote all that is wrong with the neoliberal world order. This week, at the Third WTO Ministerial Conference in Seattle, people are here to tip the scales back the other way.

Already, a great deal has happened, both in Seattle and outside. Constant civil society pressure on, and scrutiny of, trade bureaucrats in Geneva has made it impossible for member states to agree on any sort of negotiable text for the conference. This is very embarrassing for Pres. Clinton, who will be the only world leader (besides, perhaps, Fidel Castro) at the Millennial Trade Talks. It’s striking to compare this to past trade summits, where heads of state have flocked to be associated with the latest bit of trade triumphalism.

The run-up to the conference here in Seattle has seen a number of actions already. For instance, on Friday, a group from the Direct Action Network hijacked Seattle’s post-Thanksgiving department store parade. A group of well-trained cheerleaders inserted themselves into the parade, right behind the mayor’s car, and started chanting anti-WTO slogans. They put in their pitch for “Buy Nothing Day” and gave children “subvertised” dollars, with which to purchase nothing at all. The cheerleaders had clearly been to charm school — more or less everyone thought they were desperately funny.

People in the activist crowd are excited, and with reason. But it was disturbing to get into the central meeting area for activists and find myself one of perhaps 10 non-white people there, in a crowd of hundreds. The organization is committed, fierce, and segregated. With any luck this will change with the arrival of people from overseas. We’ll see.

So anyway, what’s to look forward to this week? For me, one of the highlights of the week will involve the man I’m going to be working for in Zimbabwe next year — Yash Tandon. He will be delivering a keynote address today in the official WTO non-governmental summit. Yash is the most famous man you’ve never heard of. He was a revolutionary intellectual in Uganda, but had to disappear when Idi Amin’s regime came to power. Even today, he gets people coming up to him saying, “We read about you in the history books, but thought you were dead.” Anyway, he’s back in a big way, and deeply critical of the WTO. He has been active in southern Africa persuading governments to take their power and responsibilities a little more seriously, and not to be so cavalier in giving away their countries’ rights by signing on to multilateral agreements without seriously debating them first.

It’s interesting that Yash has been asked to provide a critique of the WTO within the WTO itself — he’s far more radical than most critics, even those on the left. I wonder what the delegates at the WTO will make of him. Interestingly, he’ll be kicking off a panel of WTO critics dominated by Northern environmental NGOs. It’s not like the WTO doesn’t have environmental impacts, but it is a little disturbing that, within the official forum, a profound critique of effects of the WTO on ecosystems and people has been left to only one person from the South. It’s almost as if the resistance to the WTO is being bambified by association with the WWF and Sierra Club. As I say, it’s not as if the shrimp-turtle issue or the proposed logging agreement aren’t important — clearly they are. Rather, it is that these egregious, environmentally unsustainable agreements are part of processes which transform entire societies in both the North and South. And sometimes I fear that the environmental lobby misses this and doesn’t see the wood for the trees.

So, for me Yash’s speech is going to be the centerpiece of my day. Before he does his thing, I’ll check out the African Caucus, to hear what else is up in the world of African civil society. And after Yash has scandalized the NGO forum, I’ll leave to join a 10,000-strong human chain outside the WTO conference center. This will be followed by a rally at which Mike Moore will be the Master of Ceremonies. That’s Mike Moore of Roger and Me fame, not Mike Moore, the oleaginous head of the WTO. The regular laugh-ins are an integral part of the week’s activities. As Walden Bello said at one of this weekend’s teach-ins, the most important thing about monopolists is that they don’t have a sense of humor.

All in all, a packed day. Tomorrow, news about the plans for the N30 protest. See you then!

Tuesday, 30 Nov 1999

SEATTLE, Wash.

Monday was way too long and disconnected, rather like this diary entry, but a number of important things happened. First off, I spent the morning with the African Caucus. You’ve got to wonder when the marginalization of Africa and Africans will ever stop — the meeting took place a half-hour bus ride away from the center of town. Despite being called at the last moment, though, a good 70 people turned out to hear a variety of speakers bear witness to stories of globalization in Africa. Among the speakers was a woman who did a fine job explaining how the economic violence that puts women in sweatshops is systematically connected to violence against women in the home. This connection isn’t one that’s made nearly enough. Where, after all, do we learn to treat women’s bodies differently from men’s? This isn’t something you pick up in the workplace, though it is repeated and relearned there. Gender relations get produced and reproduced in the home, and the speaker reminded us that it was important to keep the space within the home political. The word “patriarchy” is one which we need to be unafraid of using when we talk about women in sweatshops.

After that, a quick dash across town back to the WTO conference center, for the official WTO sponsored “dialogue with civil society.” I had expected to miss the start of this, but luckily there had been a security breach — those naughty direct action pixies had managed to slip into the conference facility — and no one else had been allowed in for a couple of hours while the police scratched their heads to figure out how the breach had occurred. This threw the whole timetable back a bit and meant that I’d not really missed anything, except lunch.

A number of big-ish names spoke. Britain’s usually entertaining and outspoken Minister for Int

ernational Development, Claire Short, gave a disturbing speech in which she patronized developing countries and argued that poor countries were being foolish in wanting the WTO to hold its horses. She said that the best way to address developing countries’ concerns was not to stop liberalisation, but to have a broader “development” round of negotiations that takes their concerns into account. At the same time she praised the developing countries for their new confidence in trade negotiations, she asked them to be a little more compliant with the will of developed countries. The Minister was trying, in a very Blairite endeavour, to find a “third way” between no round and a round dominated by the usual suspects, Northern corporate interests. This seems to be the WTO’s new ideological direction. The Northern countries know that without developing country consent, the new round won’t be able to go ahead. They’re worried and, if Ms. Short’s speech is anything to go by, desperate.

Two other speeches deserve special mention. The first is Mike Moore’s. He is the director general of the WTO, and a frightening man. He doesn’t like the way he is being forced to defend himself and his organization against the barrage of international criticism, and he has recently taken to lashing out against his critics. Here are three quotes — the first from a speech Sunday night to labor activists, the other two from Monday’s NGO special session.

For some, the attacks on economic openness are part of a broader assault on internationalism — on foreigners, immigration, a more pluralistic and integrated world. Anti-globalization becomes the latest chapter in the age-old call to separatism, tribalism, and racism — the “them” versus “us” view of the world. When I was a young man the word internationalism was a noble word. It was also a word that had real meaning for labor. We took to heart the old songs about international solidarity and the brotherhood of man. But now the idea of internationalism has become something to be feared or attacked. It concerns me that many of those who sincerely want a better and more just world now find themselves aligned with those who stand against internationalism in all its forms. I guess globalization is the last “ism” to hate.

Moore is right in some ways. There are some groups that are fiercely isolationist and chauvinist. Some European right-wing groups, for instance, tried to spin the meaning of the June 18, 1999, protests against capitalism into being anti-Semitic. For them, resistance to globalization is an act of hatred. But these right-wing groups are very much in the minority. In fact, Moore gave his speech to a room in which 120 countries’ labor movements were represented. The pertinent “them/us” distinction was not a “tribal” one, but rather the simple difference between the haves and the have-nots. And it is unlikely that Mr. Moore could have found a better example of transnational solidarity than the group staring him in the face. Suffice it to say that he didn’t fare well in question time after he accused the international union movement of racism.

Perhaps Mr. Moore could avoid this sort of critique by arguing that the people in the room with him yesterday weren’t representative? He did exactly that in his speech today:

Trade is not the answer to all our problems, but it provides part of the solution. Fifty thousand people may be demonstrating against us at Seattle. But remember too, that over 30 countries — some 1.5 billion people — want to join the WTO. They know what it offers and they want to be part of it. Ask them what they want.

It is, of course, pure fancy to think that the billion people in China, or the hundred million in Russia, have, with one voice, made an informed decision about membership in the WTO. In fact, the reason that 50,000 people are on the street is precisely because the governments that claim to speak in their name at the WTO haven’t secured their consent about WTO membership at all. Frequently, though, Moore uses the rhetorical tactic of letting the actions of a small minority represent the voice of many. Another example:

We all want a fairer world, a world of opportunity accessible to all. Just ask the mother with a sick child who wants the best medical advice the world has to offer — whether it’s from Boston or Oxford or Johannesburg.

This cheap trick, in which some fictional mother and child are meant to put a benign human face on globalization, was burst, heartbreakingly, during question time by a representative of the Africa Trade Network. The representative told how, last week, she buried her aunt and cousin, both of whom had died of preventable diseases — medicine which would have cured her relatives was not available because it is protected by the WTO patent system and cannot be reproduced generically for another 10 years in southern Africa.

The other speech I want to mention, quickly, is the one given by Yash Tandon, of the International South Group Network. As I mentioned yesterday, Yash was probably more radical than anyone else in the room. His speech was delightfully incendiary. First, he criticized himself, together with other members of civil society, for failing to do more to inform and criticize during the early 1990s. He criticized the governments of the South, for signing away the birthrights of their people. His final criticism was leveled at the corporations and developed country governments that call the tunes to which Southern governments, often reluctantly, dance.

Question time was the chance for other members of civil society to have their say. Unions voiced their concerns that labor standards are not included in the WTO (much to the consternation of trade economist and self-proclaimed intellectual leader of the free-trade movement, Jagdish Bhagwati). Environmental groups talked about how the WTO was overriding existing multilateral environmental agreements. A range of business groups did some slick work to push their own agendas. This is all fairly standard for these sorts of affairs.

There were, however, a range of other groups whom you might not expect to have seen. The women’s caucus tried to point out that international trade theory rests on some pretty gendered assumptions, but they were brushed off by Bhagwati, who accused them of being “illogical.” The relief agency Medecins Sans Frontiers — Doctors Without Borders — was there, arguing that patents on medicines are killing their patients. And the World Union of Librarians was there arguing for a robust domain of public information, and putting the case against the commodification and homogenization of culture.

We’d do well to remember, though, that despite a farrago of star speakers, there were many silences. Very few women’s movements made their presence felt. And everyone except the French spoke English. Surely there are people who can’t speak English, who nonetheless have trade-related concerns? In any case, Mr. Moore had, by this time, left the room. He seemed less interested in dialogue than monologue, and many NGOs criticised the process for not even having the veneer of participation. The whole afternoon appeared to be merely an opportunity for NGOs to vent, without actually influencing anything. This consultative session was more a testament to the WTO’s fear of civil society than any sort of willingness to engage with it.

So many other things happened today. There was a 10,000 person human chain in support of debt relief, at which a great many more than 10,000 showed up, thanks in no small part to fierce organizing by the U.S. unions. There was a People’s Gala, at which Kevin Danagher of Global Exchange claimed that we’re on the brink on the first Global Revolution. Although I’d question his sense of history, there does seem to be something electric in the air. There’s certainly a feeling that tomorrow, the main WTO protest, is going to be big. And noisy. The WTO is right to be afraid.

Reports from the streets tomorrow!

If you’re interested in knowing more about what went on, visit http://www.iisd.ca for a comprehensive summary of the proceedings. The International Institute for Sustainable Development is a fine organization, and are likely to do as good a job with this as they have with past efforts.

Wednesday, 1 Dec 1999

SEATTLE, Wash.

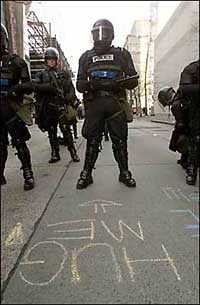

I don’t know where to begin. You must know by now that the international day of protest was a great success — we shut down the WTO opening session, most of us made it out in one piece (tear gas notwithstanding). We seem to have won the battle for the public’s hearts and minds, for now. The WTO opening ceremonies have been cancelled, and there’s a very bitter air in the governmental delegations here. I even saw one besuited diplomat assaulting an activist (who was wearing a “this is a nonviolent protest” t-shirt) screaming at him to let the delegates into the conference center.

Protesters form a human chain in an intersection.

Photo: Sherry Bosse.

If you weren’t here, however, you might have an odd picture of what happened. The media presentation of what took place in Seattle is, as you would expect, deeply skewed toward the dramatic moments of protest. To be fair, the local TV station in Seattle did a good job of not portraying the protesters as barbarians. Some were allowed to speak for themselves, and the message that the actions were nonviolent came across fairly well. Everyone seems to believe that the protestors, in large part, did not cast the first stone in the Battle of Seattle. Nor, come to think of it, did they cast any of the tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets, or concussion grenades.

But, having scanned a few news sources, there are significant, and systematic, gaps. Looking at the front pages today, one would be forgiven for thinking that newspapers exist for those concerned, above all, with the physical integrity of downtown Seattle’s shopping district. A voice-over line used repeatedly during the live TV coverage was, “The scenes of rioting here are a real contrast to the usual holiday shopping season.” It is, historically, odd that this remark should be considered normal — once, the streets used to be the place for politics. It’s a sorry reflection that urban public space is now only understood as the area between stores.

Concentrating on the disruption to the holiday season consumption fest doesn’t really do justice to what happened here. I don’t want to contribute to the imbalance any more than I have to. I, too, could tell you about being caught in tear-gas clouds, and how the police wouldn’t give water to a friend who had an allergic reaction to the gas and very nearly died. I could chip in my two bits about comrades beaten by the police, or the McDonald’s rapidly (and pleasingly) defaced early in the afternoon by the minority of non-nonviolent protesters. Or about the “dark side” of the protests — the anger of breadline workers whom we prevented from getting to their jobs, the sometimes unreasonable property damage, or the physical violence meted out to one or two individual delegates.

Sure, all these things happened. We already know where to go for more of this sort of news (see the Washington Post, New York Times, CNN, and for pictures, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer [sic]). Even the good folk at the Independent Media Center sometimes veer toward the spectacular, although their coverage is largely fantastic.

It is, however, harder to find coverage about the more, um, pedestrian moments yesterday. Like the marches. Or the labor rally which preceded the downtown spat. This is an egregious omission since between 30,000 and 50,000 labor activists were at the AFL-CIO rally. Moreover, the U.S. unions went out of their way to try to make it a genuinely international affair. Trade unionists from South Africa, Barbados, and even China (a soon-to-be member of the WTO) spoke out against globalization, shoulder-to-shoulder with their U.S. counterparts. Even Vandana Shiva got to do a little rabble-rousing. And despite a little jingoism and flag-waving at the end of the rally, the rally wasn’t about the raised voices of national protectionism (though there are clearly protectionist impulses here). This looked, and I can find no better words to describe it, like International Workers’ Solidarity. People from different countries, from different sectors and political perspectives, acting as if a blow against one were really a blow against all.

This didn’t really come out in the press — the best popular press effort I’ve seen has been in the New York Times, but even their coverage individualizes the different struggles. Certainly, people have different concerns, but it is surely more significant that despite these concerns, they are able, however provisionally, to stand together.

The other omission in the coverage of Seattle is that Seattle is just one of a number of places in the world where actions against the WTO are taking place. Hundreds of places had N30 actions. Mike Morrill, of the Pennsylvania Consumer Action Network, put it eloquently in an email earlier today: “While the events unfolding in Seattle are historic, let us not forget that this is a global movement. The tens of thousands of people in the Seattle streets were joined by people in communities around the world. … Two dozen people who care enough to pass out flyers to holiday shoppers have involved themselves enough to begin creating a community network which, when linked to other local networks, can evolve into a movement. I’ve heard too many people complain that their local actions were insignificant, when nothing can be further from the truth. Don’t play the media’s numbers game.”

Would you like fries with that?

Photo: Sherry Bosse.

For my part, I’m really proud to be associated with a group of citizens and students in Ithaca, N.Y., who organized a day of protest yesterday, and who, by all accounts, got one of the largest turnouts of any protest in recent memory. This is a deeply encouraging start. It is in our communities, after all, that the war against globalization will be fought, not in Seattle. As I look out now, I can see the glaziers coming to repair the McDonald’s. Within a week, there’ll be no sign that any of this ever happened.

Some of my friends go misty-eyed when they recall the day, a couple of years ago, that the Labour party returned to power in Britain, after nearly two decades of conservative rule. Back then I was a little less enthusiastic than they, but this morning, I think I know what they must have been feeling. It has been so long since the resistance won a battle as substantial as this. Clearly, the next step is not to let the fervor die. But, for the moment, perhaps a couple of hours to enjoy the victory.

Tomorrow, more detailed, and less editorial, stuff on “Gender and the Global Economy,” which is today’s theme at the WTO.

Thursday, 2 Dec 1999

SEATTLE, Wash.

As the protests in Seattle continue, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to navigate the torrent of misinformation in the media. It is true that downtown Seattle has been transformed into a nominal war zone. But I say “nominal” because, other than a couple of hours of exceptionally violent street-clearing by the city’s finest, downtown Seattle was pretty quiet yesterday. (The main disturbances seem to have happened in a neighborhood a

little removed from the downtown area.) The mayor has, however, in effect created a war zone downtown. By signing a declaration of a state of emergency, he has overridden the peaceful reality of nonviolent protests and militarized 60 city blocks.

This means that all rights are suspended for the duration of the WTO conference. All of them. A group of protesters came in to the city center at 7 a.m. the day after N30 to help clean up the mess. The police wouldn’t let them in because they were wearing anti-WTO paraphernalia. And any civilian found in possession of a gas mask within the no-protest zone will have it confiscated and face an additional six months in jail. Notice how, as soon as you enter the zone, you stop being a citizen with rights, and become a civilian, a threat, a subject for military control. All because someone drew up a map and signed some paper.

The transformation of space is never so complete, though. I was out after curfew last night, wandering the streets looking for friends. I wasn’t alone. The shops in the downtown area were still open. Expensive restaurants still catered to delegates. Liquor stores still sold grain alcohol to anyone who could afford it. The police drove up to me and very politely reminded me that I was in violation of the state of emergency, and if I’d please move along, they’d be very grateful. Different from the random beatings earlier in the day, no?

So don’t be believing the sweeping generalizations about downtown being in the iron grip of Terror. This is a very selective persecution. Only people who want democratically to express their dissatisfaction with the present regime are being targeted. (The targeting skills of the police aren’t terribly good, though — there was a great deal of “collateral damage” earlier on today, when office workers and passersby were also caught in the clouds of tear gas and beaten by the police.) For us, the protesters, Seattle is a police state. But for the rest of Seattle, it’s business as usual. This is very, very frightening. Think about it for a second. The delegates can go about their business, the downtown homeless can eke out a living, the stockbrokers can make their fortunes, even some NGO members can shuttle back and forth and not notice the difference between a state of emergency where rights are suspended, and regular everyday times, when the rights exist but no one wants to use them. This is the land of the free, but everywhere, it would seem, people are in chains.

I heard some important perspective on this from a friend from the Philippines. She told us that two weeks ago, in Manila, a few days before an Asian ministerial meeting, a shantytown near the convention center was gassed and bulldozed. Two people were killed — an elderly woman died of a heart attack, and an infant suffocated on the CS gas (made in America, traded around the world). This violence happens everyday in the Third World, but the voices raised in protest there don’t seem to carry very far. Now the violence is on the streets of a developed country, it is visible, in our faces, and inescapable. Ultimately, the Battle of Seattle could just be chickens coming home to roost — the economic deprivation and social division brought about by inequitable institutions isn’t limited, after all, to the South.

So what about the voices raised here? Reading the popular press, you could be forgiven for thinking that the only thing the protestors are doing is having the crap whacked out of them. This isn’t true. Sure, there’s blood on the streets (drawn by King County’s finest, never by protesters). I have yet to find information in the national press, though, on what the protesters have done since being arrested.

They’re still resisting, and resisting with humor. There was a fantastic image of them on local TV yesterday at the police holding facility specially set up to “process” them. The busses had arrived, and the fingerprint takers had their ink pads all set up. But the activists wouldn’t get off the bus. They were staying there until they were given access to a lawyer and given a phone call. And the police really didn’t know what to do with them. They were let off the bus to go to the bathroom, and then let back on the bus. And last I heard, they were still there, after 18 hours. Fighting back, nonviolently, and with compassion.

Resistance isn’t just limited to the streets, though. Governments can resist other governments too. Not all governments are the same. It is possible, just as the protesters on the streets have been doing, for delegations from the South to speak truth to power. In the WTO sessions themselves, you can see small, and uncoordinated, but nonetheless real acts of resistance. A quick bit of WTO background first.

At the Singapore ministerial meeting in 1996, the U.S. and EU decided that they wanted to have some new issues brought to the negotiating table. It was decided that committees would be formed on these new issues, and would report back to the member states. The committees still haven’t completed their work, but the U.S. and EU are getting impatient. They’re pushing through a declaration on new issues at the moment. And developing countries are furious. There was an official session yesterday to debate this. Developing countries took the floor and vented their anger. In the afternoon, the New Zealand chairperson brought out a draft text for discussion. It was the same text on new issues that had been circulated in Geneva a few weeks ago, and which had been rejected by developing countries even then. The morning session had, in effect, been entirely useless — an opportunity for developed countries to appear to listen to developing ones, without actually doing so.

It gets worse. The U.S., EU, and Canada have been selectively buying off key developing countries with bilateral concessions. This means that solidarity between developing countries is weakening. The game plan seems to be that these client countries will sit, together with the big players, and draft a document which will be rushed through a brief committee meeting early tomorrow. This is how things get done by consensus at the WTO.

Developing countries aren’t as well organized as the protesters on the streets, but they are acting. I’ve seen delegates pushing the bigger developing countries (e.g., India and Brazil) to take a stand. I’ve seen documents being leaked to developed country NGOs, which will then take them to their governments to embarrass them. And I’ve seen delegations from the South talking for the first time, if only sotto voce, about some sort of coordinated non-cooperation. It’s not much, but it’s a start. And it’s just as much a fight against power as the street politics outside.

The last thing I want to touch on is the disturbing division in the popular press representations of the violent and nonviolent protesters. On the local TV station last night, a report showed an encounter between a young masked, white man and four or five young Latinos. The masked man was trying to argue against violence and property damage, and the Latinos were saying, “Well, why not, it’s just some fun.”

The argument made explicitly by the reporter was that not all protesters are violent, but it’s just a hard core of unrepresentative people who spoil it all for everyone. This is called “balanced reporting.” But there’s always a subtext. In this case, the subtext was that these undesirables are Latinos, and that they are not open to reasonable dialogue. Maude Barlow, of the Council of Canadians, was movingly eloquent on this issue yesterday. Her words (and I’m paraphrasing here, unable to do justice to the force of what she said) went something like this:

“The press tells us that there were undesirable elements, that there were some people who didn’t know why they were protesting, that they didn’t know what the WTO was, who were smashing win

dows just because they could. So what? They are our children, products of our social system. You can’t tell me that they don’t know what politics is. They are hungry, and they are angry. They are the street politics that the WTO regime has spawned, and the people inside the WTO building can’t hide themselves from that.”

We oughtn’t to let ourselves buy the divisions peddled to us by the thoughtless and the privileged. What’s important about the protests, both inside and out, is a confrontation between the powerless and the powerful. If we’re serious about redistributing that power, we must resist the demonization of friends who are as angry as we are, but whose protest we don’t find as “articulate” or informed.

Sorry not to write about the gender and trade things, which happened yesterday but were disrupted by the street fights. I want to write about these, and will next time.

Sunday, 5 Dec 1999

ITHACA, N.Y.

“Seattle — It’s a Gas”

— A protestor’s sign at the Jail Solidarity Demonstration

“[The protests in Seattle] indicate the remaining damage that Marxism has done to the thinking of people.”

— Rudolph Giuliani, mayor of New York

“If free traders cannot understand how one nation can grow rich at the expense of another, we need not wonder, since these same gentlemen also refuse to understand how in the same country one class can enrich itself at the expense of another.”

— Karl Marx Weeks like this don’t happen often. I began writing this final diary entry on the plane out of Seattle on Friday, the last day of the conference. And at the time, it looked as if we’d had a good week, but that the WTO was lumbering toward an agreement, and that the 600 jailed protestors weren’t going to be released any time soon. But, 48 hours later, we’ve won on all counts. The WTO has been eviscerated, and the political prisoners are free. This feels good. Very good.

Protestors flood Seattle streets last Thursday.

Photo: Sherry Bosse.

There are a number of reasons why the talks failed, and the history of what happened won’t stabilize for a while yet. Among the reasons I’ve heard are, first, that the EU and U.S. couldn’t come to an agreement over agriculture. The EU came to the negotiating table with talk of how agricultural support for farmers does more than just “distort” prices — these supports are actually a way of sustaining a rural livelihood which otherwise would be obliterated by the market. The code word for this within the WTO is “multifunctionality.” The U.S. didn’t agree with this, and after much haggling, the EU seemed prepared to drop any mention of this from the final negotiating text. The rumor is that when this was announced, French farmers kicked up an almighty fuss, so that by close of business in Paris on Friday, a split had occurred in the EU position. And when the day started in Seattle (which is nine hours behind Central European Time), the EU and the U.S. found themselves having to start all over again.

The agricultural differences are important, but I can’t help feeling that, in the absence of any other difficulties, these differences might have been overcome. The further disagreement between Southern nations and the U.S. over labor and environmental standards might have been overcome too, with a little goodwill. But walking around the corridors of the WTO convention center, it was goodwill, more than anything else, that was in short supply.

The developing country delegates in particular had plenty of reason to be angry. Throughout their stay in Seattle, they’ve been patronized and treated with disrespect by their hosts. After a particularly condescending speech by Charlene Barshefsky, the U.S. trade representative, on Thursday, some Southern trade ministers booed. This may not sound like much compared to the action on the streets outside, but it is unprecedented in the history of trade negotiating. Trade diplomats are meant to be diplomatic. Booing, in the protocol of international relations, is the equivalent of a solid kick in the groin.

Among developing countries, it appears that the African nations were particularly marginalized. On Thursday, African trade ministers had a meeting to try to thrash out a common position. After about 45 minutes, the microphones in their conference room mysteriously went dead. And no one could be found to make them work for an hour and a half. (When the Teamsters’ microphones died on Friday, they were fixed in five minutes flat. Odd that. A lot of microphones dying in Seattle. I’m sure it must have happened to the U.S. delegation too, but we just didn’t hear about it. Something in the air, no doubt.)

One of the African trade ministers decided that, rather than wait around, he’d go to the committee on agriculture. The security guards at the door wouldn’t let him in. The guards didn’t doubt the minister’s identity — his identity badge stated very clearly that he was the minister of trade from Ghana. But they insisted that, to enter the room where deliberations were taking place, he needed an invitation. There is, of course, nothing in the WTO rules about this. All meetings are meant to be open to all member states’ appointed representatives. The minister made an unholy racket in the corridor. The guards still refused him entry. Eventually, after a good 20 minutes, the minister gave up. When he returned to his hotel later that evening, he found a plain envelope under his door, with an invitation to participate in the agriculture panel. The invitation was unsigned.

So on Friday morning, the African trade ministers wrote a statement, in which they declared their anger with the WTO’s negotiating procedures. They observed that an institution with unfair procedures must find it hard to claim that the rules it produces are equitable. The Latin American countries put out a similar statement, and both regions were supported by a range of Northern and Southern nongovernmental organizations.

The bitter atmosphere of the preceding days intensified as the U.S. and EU tried to revert to old habits and called a “Green Room” meeting late on Friday. The “Green Room” was a venue at the old General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) secretariat (which mutated into the WTO), in which powerful countries haggled over trade policy, and from which the South was routinely excluded. A couple of Southern countries were invited into the room, to preserve appearances on Friday, but it was impossible to pull together an agreement which everyone would sign. And so, with chants of “AF-RI-CA! AF-RI-CA!” faintly audible from the streets outside the county jail (where protesters had gathered in solidarity, and where information from inside the WTO was being relayed), developing countries made it politely clear that if they’d not been given a chance to participate in negotiating a text, they weren’t in the mood to sign.

In the popular press, though, there seems to be an odd schizophrenia about why the talks failed. The three stories — division within the EU over agriculture, U.S. insistence on standards, and new developing country intransigence — are told as if the trade diplomats had fabricated these issues out of thin air to annoy their colleagues. And meanwhile, a world away, the protesters are beaten and tortured in the jails of Seattle. As if these two worlds weren’t the same, weren’t intimately related. But clearly, the division between the EU wouldn’t have happened without French farmers. The U.S. wouldn’t have been so reluctant to compromise over labor and environmental standards without the AFL-CIO and Sierra Club breathing down Clinton’s neck. And developing countries wouldn’t have been so confident without the tireless and unacknowledged work of dozens of NGO activists whom I saw brokering meetings between ambassadors, prov

iding information, and, in general, agitating. The distinction between “high” and “street” politics is particularly unhelpful.

Spectacular victories aside, though, perhaps the most important victories have been more subtle than the release of prisoners and the disruption of trade talks. The possibility of solidarity between different groups, the realization that, together, groups can change the world, and can start the change by starting with themselves, is something that certainly I have never felt before. Not like this.

The feminist scholar Nancie Caraway in her book Segregated Sisterhood talks about the necessity of crossover politics. Crossing over recognizes that we’re each coming from a different history and background, but that we need to respect each other’s positions if we are to overcome the divisions that history attempts to drive between us. This week has been a first step in what I hope will be a more permanent politics of mutual respect and solidarity. Because it is, if nothing else, necessary. At the farmer’s rally on Thursday, a black farmer from Georgia put this very powerfully. He said, “I don’t suppose you folk know what it’s like to be denied a loan for improving your farm because you’re black. And I don’t suppose you know what it’s like not to be able to increase the size of your farm because of how the other [white] farmers will react. I don’t suppose many of you folk know what it’s like to be called a nigger. I get called a nigger a lot. But organizations like the WTO are going to make niggers out of all of us. And it’s not like the shoe is on the other foot. It’s that we’re now all in the same shoe.”

This attempt at connection was something that cropped up in the gender workshops held on Wednesday, about which I’ve been threatening to write for a little while. To be honest, I was hoping for more. It is obviously important to note the ways in which globalization affects women differently from men. There’s an interesting paradox in the way neoliberalism works with respect to women’s bodies. Trade barriers are being reduced at the same time as immigration and refugee policies in Northern countries become increasingly draconian. It is much harder now for people from the South to come north than it has ever been in recent history. It is, by contrast, much easier for the commodities produced by these people to come north. Trafficking women as laborers in maquiladoras (to read more, visit Global Exchange’s website) or as sex-workers is a way of circumventing this — the trade in women treats them not as people, but as commodities. Perhaps I’m missing something, but I only heard one or two people making the connection between the gendered character of globalization and the way in which women are treated in the home. And, as I wrote on Tuesday, this is one of the most pernicious power asymmetries exacerbated by globalization, because it is silent. We need to be making more noise about this.

These protestors know what they want, what they really really want.

Photo: Sherry Bosse.

But this grumble aside, there is much to be joyful about. I spoke to a labor activist who was in Chicago in 1968. He said that Seattle ’99 was in many ways far more exciting — “the range of groups represented, the camaraderie between the groups, and the sense of urgency seem more acute now. And people seem to know what they want a lot better. I am hopeful. You’re lucky to be alive right now.” I agreed.

The only thing that perhaps compares to the Seattle experience in my lifetime was the Rodney King riots. I ran into a young, homeless woman who had been in L.A. at the time. By her own admission, she’d only gone down to L.A. to “fuck shit up,” but she did say that the atmosphere in Seattle was entirely different. She was well-informed on why the WTO was a pernicious institution. I even detected a note of pride in her voice when she was able to list three reasons why the WTO ought to be shut down. Right there, right there is what we’ve achieved this week.

“This is what democracy looks like” is a chant we used a great deal on the streets this week. Knowing enough to participate in a functioning democracy, and knowing that the democracy will listen, makes you feel proud of yourself, value yourself, in a way that I, for one, have never felt before. It’s a shame that it’s only now that many of us are starting to feel it. Better late than never, though.

We’ve a chance now, an opening, to start re-imagining our world. Not that we didn’t have the power to do this before. But I think it’s taken something like this for all us to realize just how much power we actually have. It’ll take a lot of unsexy, undramatic, unspectacular organizing to make our dreams real. Seattle was, after all, only a first step. Other campaigns next year include the International May Day celebration and the NATO ministerial in Italy, as well as, of course, Earth Day 2000. The real transformations, the hardest battles, won’t be fought on the streets of Seattle, or Milan, or at any spectacular gathering. They’ll happen every day. In our homes, at work, in our practices and relationships. I don’t for a moment imagine it’s easy. I’m not even sure where to start. But it’s great to be alive right now.

For more on the WTO and Seattle protest, visit The Voice of the Turtle in the next few days!