The summertime rain that usually pounds Louisiana in fits and starts had been falling for a day and through the night when Shantel Smith’s phone rang. “My oldest sister called screaming, ‘I’m flooding out, I’m flooding out,’” she said. “Then the phone went dead.” Smith and her son, her sisters and their kids, and her mother and grandmother had moved to Baton Rouge from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina flooding upended their lives. Family history was about to repeat.

Smith and a brother-in-law drove a pickup through flooded streets to help. “Every street we went down, as close as we could get to the home, there was water,” Smith said. Her family would survive, but by nightfall, all four households would be driven from their homes. Like tens of thousands of other Louisianans, Smith’s family hasn’t recovered in the year since the Great Flood, as locals have taken to calling it.

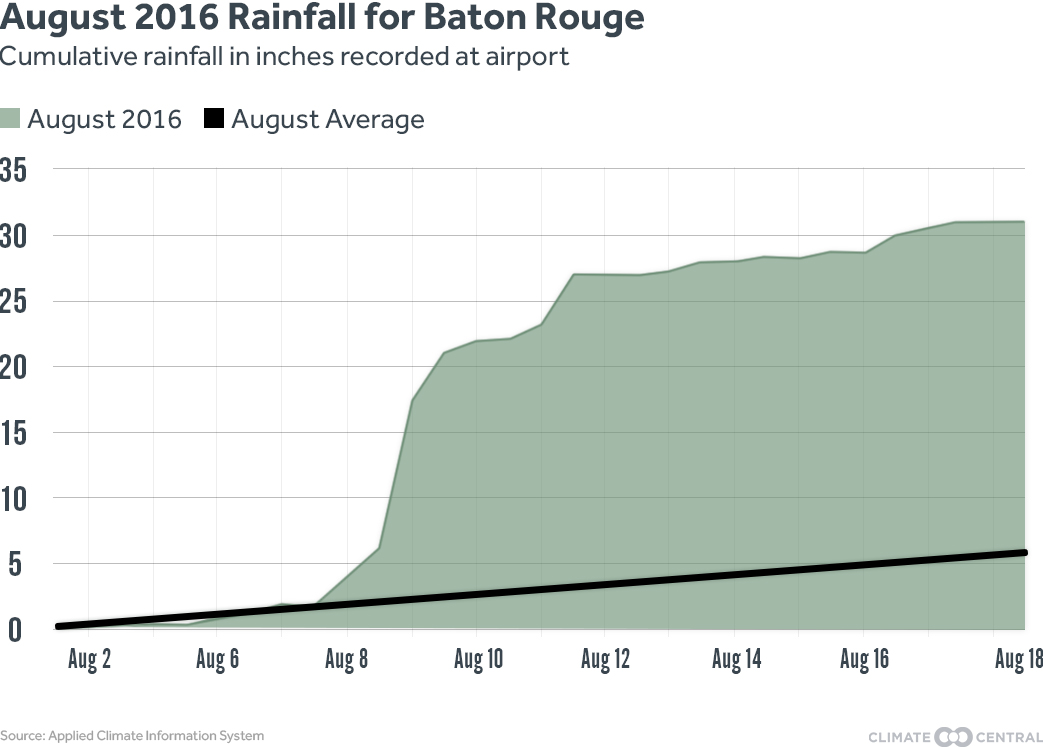

The worst rainstorm in a rainy state’s history began innocuously when a low-pressure system formed early last August near the coast. A week later, the system had barely budged, boxed in place by other weather patterns. From Aug. 11, it erupted for days with unimagined force over a sweeping stretch of the Pelican State, bringing more rain than Hurricane Katrina.

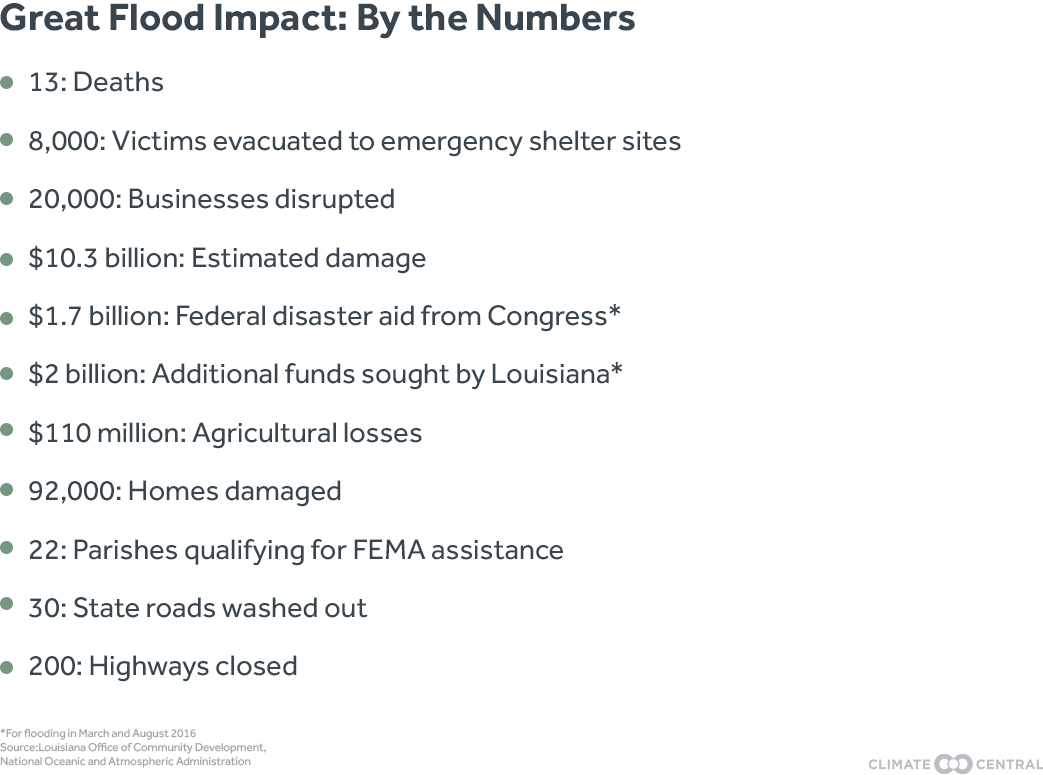

In some places, more than two feet of rain fell over three days, overtopping rivers and canals. The flooding killed 13 and affected hundreds of thousands, causing major damage to tens of thousands of homes. Research has shown it was one of the worst storms yet to have been clearly linked to climate change. The estimated $10.3 billion in damage ranked it as one of the worst floods in American history, but the national reaction has been muted in the year since. (Northern Louisiana was hit by flooding that caused $2.3 billion in damage earlier in 2016.)

The storm in August had no name and it affected a neglected corner of the country. At the same time, the Olympic Games and a divisive national election reduced news coverage, leaving national reports on the flooding scarce. A New Orleans Times-Picayune movie critic wrote a week into the disaster that “locals have every reason to worry that recovery funds will be just as scarce.”

The storm left families struggling with twin traumas of losing everything and feeling abandoned at a time of need. The victims include some of America’s most vulnerable residents, many of them poor, many of them living in households headed by single working women like Smith. Survivors have struggled not just to rebuild their homes, but their lives, with psychological wounds festering long after flood waters receded.

Nickels to the dollar

In the parts of Louisiana hardest hit, including Baton Rouge, more than one in four households live in poverty. There are visible signs of national neglect as Congress has provided nickels to the dollar to help Louisianans recover. Turning off the main roads into the side streets of northern Baton Rouge reveals how the devastation disproportionately affected the most disadvantaged.

America deals with disasters by throwing money at them after they hit, which federal, state, and local agencies use to rebuild homes, businesses, and infrastructure. The federal government spent $278 billion on disasters from 2005 through 2014, the Government Accountability Office reported. The amount of money that follows a disaster depends largely on the whims of Congress. That puts victims of low-profile storms in politically weak states at risk of being cast aside as requests for aid tick upward with global temperatures.

For every dollar of damage caused by the 2016 floods, Congress is providing Louisiana with 13 cents to help it recover. The funding seems “low for the level of damage that occurred,” said Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, deputy director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

Compare that with the 65 to 70 cents to the dollar for recoveries following hurricanes Sandy in the Northeast and Katrina in the Deep South, which were the most damaging storms in U.S. history and received far more attention. “This was not a well-covered disaster,” he said. “Not a lot of people know about it.”

Presidentially declared disasters tend to qualify automatically for some recovery funds, with lawmakers charged with passing bills to boost the amount for catastrophes and disasters not usually covered. To help Louisiana recover from the 2016 floods, Congress raised $1.7 billion through amendments to three separate bills — $2 billion less than state officials say is needed. Governor John Bel Edwards has asked Congress for more.

“Congress is getting a little frustrated with these emergency supplementals,” Schlegelmilch said. Disasters are increasing nationally and globally, and he pointed out that America’s approach to funding recoveries was created in the 1970s and 1980s, when the nation’s political climate and its vulnerability to extreme weather were both more tempered. “They’re very large-ticket items that are put out there, and they’ve gotten more difficult to pass.”

FEMA is considering requiring states to help fund their own recoveries by paying deductibles. That could hurt poor and disaster-prone states like Louisiana and its Southern neighbors, though the agency argues in a rulemaking notice that it would “incentivize greater state resilience to future disasters.”

Schlegelmilch supports reforming the current system, which emphasizes recovery efforts over preparedness. (Research has shown that spending on preparedness substantially reduces spending on recoveries, but that U.S. voters prioritize the latter over the former.) “We need to do more to incentivize state and local investments in mitigation for climate change and for other kinds of disasters, so that we’re not waiting on a bailout every time that disaster strikes,” he said.

The unseen toll

The forlornness of families and the mental health maladies from their trauma are less visible than physical scars etched in urban streetscapes.

“You see people who still don’t have homes, and it’s so sad, it’s heartbreaking,” said Katherine Washington, a 59-year-old teacher living with a daughter and foster daughters in a FEMA trailer in their north Baton Rouge yard while their house is repaired. Their furniture, clothes, photos, and toys were destroyed by the flood. Later, thieves took Washington’s washer and dryer from her wrecked laundry room and the tires off her flood-damaged car. Their street is still pocked by empty houses.

The August flooding came with little warning, and flood survivors suffer panic attacks when it rains, fearing a repeat. Baton Rouge is one of America’s rainiest cities, making for frequent dread. The rain fell from an unusual storm that weather forecasters underestimated, compounded by drainage problems through a low-lying region.

“The water came so fast, you didn’t really have time to think. All you wanted to do was get out, get out, get the kids and get out, and that’s what we did,” Washington said. “After the flood, I couldn’t concentrate. I just couldn’t do anything. My mind was trying to comprehend what was all going on.”

The storm was expected to deliver heavy rain, though the record amounts took experts by surprise. “There was no precedent for this event,” said Joshua Eachus, chief meteorologist at WBRZ, an ABC affiliate in Baton Rouge. “The human mind fails to grasp what could occur when you get to amounts that high.”

Survey data by Louisiana Spirit, a state agency that uses federal emergency money to help victims recover following presidentially declared disasters, shows thousands are suffering from sleeping and eating problems, shakiness, and despair. A quarter of survivors surveyed told agency staff they’re having trouble making decisions. One in five said they feel irritable and angry. Police figures show domestic violence has increased. So, too, has drinking.

“You may be so stuck in depression that you can’t move forward,” said Paula Davis, clinical director at the Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Baton Rouge, which is using federal grants to help hundreds of households recover physically and emotionally from the floods. Recovery can be hard in a hotel or a trailer, or piled into relatives’ houses, waiting for contractors or the government to make damaged homes livable again. “Think about being with your wife in a hotel for a year,” she said.

Compounding the shortage of money for rebuilding infrastructure and private property, mental health support is drying up. The Trump administration denied a request from the state’s office of homeland security to fund a program providing group counseling sessions and other mental health services beyond this month, frustrating state and local officials.

“We need to keep this topic of the long-term mental health impacts to our community on the forefront,” said Baton Rouge Mayor Sharon Weston Broome, who has been living with relatives since the Great Flood damaged her home. Like most of the houses that flooded in Louisiana a year ago, hers was not built in a flood zone, meaning it wasn’t insured against the damage. “When we look at recovery, we have to look at it holistically.”

Possessions destroyed by the flooding pile outside a vacant house in north Baton Rouge nearly a year after the storm. Ted Blanco/Climate Central

Depressive disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder, which are afflicting Louisianians in the wake of the Great Flood, can be common after a disaster. Women are more likely to develop depression and anxiety and men are more likely to turn to drugs and alcohol, said Carol North, a psychiatry professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

“The majority do not develop a psychiatric disorder, but almost everybody who experiences a direct hit of trauma experiences some kind of emotional distress and suffering — it’s virtually universal,” North said. She copublished an analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association of the mental health effects of disasters described in hundreds of scientific studies.

While the floodwaters affected a large segment of south Louisiana’s population, both rich and poor, the poor lack the resources to quickly rebound. North Baton Rouge’s residents work as nurses, teachers, and in hospitality, often in low-paying to middle-class jobs. There are artists, activists, and business owners. Others rely on welfare; some here are destitute. Census data shows many households headed by single women. The area has few large stores. Some residents commute to the city’s south to work in restaurants and other businesses — a difficult trip for those who lost vehicles to the flood.

The poorest victims “were totally dependent on the government,” said Cecile Guin, who directs social service research at Louisiana State University. “The people that could afford it, they were traumatized, but they had the finances to start rebuilding and to clean up pretty much right away after the flood. The other people are still, well, many of these neighborhoods are still a disaster.”

This storm and other disasters could make a poor state poorer still. When researchers examined 90 years of data related to economic and population changes following storms, forest fires, volcanic eruptions, and other disasters, they found that populations tended to shrink while poverty rates tended to rise. That may be because the wealthier residents left affected areas, condensing the more vulnerable Americans in the most vulnerable regions.

“The poor have the least ability to self-protect against Mother Nature,” said professor Matthew Kahn, chair of the University of Southern California’s economics department and one of the authors of the report, published in May by the National Bureau of Economic Research. “Being poor poses many problems. Another problem with being poor is you’re likely, given budget constraints, to live where rents are cheap, and rents are cheap in places that are less desirable — in this case, areas facing more natural disaster risk.”

A survey by Louisiana State University’s Reilly Center for Media & Public Affairs indicated that a quarter of Louisianians lost income because of last year’s floods or lived in a home that flooded. Nearly half of those surveyed from the wider Baton Rouge area reported at least one of those impacts. The recovery has been slow and difficult, with a poor and vulnerable state prioritizing the use of limited recovery funds to help its poorest and most vulnerable.

Schools and churches closed for repairs after the floods, often for months, forcing parents to look after kids while juggling work, dealing with contractors, and waiting for government appointments. Religious communities had nowhere to pray during torturous times. A 120-bed Salvation Army shelter that houses the homeless and provides faith-based drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs was evacuated and badly damaged. Cars and trucks were destroyed. Salaries were replaced with unemployment checks.

Climate shocks will only get worse

United Nations data shows floods and other disasters are becoming more frequent globally, with 346 of them affecting 100 million people in 2015. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration figures show losses from disasters causing at least $1 billion in damage apiece are rising more than 5 percent each year on average.

The rise in large disasters has many causes, including growing populations and building along coastlines, in floodplains, over earthquake faults and in other vulnerable areas. It’s expected to continue to get worse with global warming, caused by heat-trapping pollution from fossil fuels, biofuels, farming, deforestation, and other industrial activities.

Analyses by two teams of scientists have linked Louisiana’s Great Flood with climate change. The rain was caused by an unusual atmospheric swirl that sucked balmy waters from the Gulf of Mexico and dumped them unrelentingly over land. A weather balloon recorded some of the greatest amounts of water in the region’s atmosphere ever detected.

A team of scientists coordinated through Climate Central’s World Weather Attribution program, which conducts rapid autopsies of extreme weather, used models and historical data to conclude greenhouse gas pollution made the extraordinary volume of rain that fell Aug. 12 to Aug. 14 twice as likely, compared with a century earlier.

“What we found is that it increases both the probability of an event like this as well as its intensity,” said Sarah Kapnick, a NOAA climate scientist who worked on the analysis. The findings were publicly released and submitted for peer review three weeks after the flood, then published in a European Geosciences Union journal.

An analysis of weather conditions was published by Utah State University scientists in November showing greenhouse gas pollution increased the likelihood of such a storm socking the region 20 percent since 1985.

“We found that the background climate — the circulation pattern — had changed in such a way that it has increased the odds for such weather,” said Robert Gillies, Utah’s state climatologist. He was a member of the research team, which published in an American Geophysical Union journal.

State meteorologist Barry Keim, a professor at Louisiana State University who wasn’t involved with either study, prefers not to blame individual storms on warming. But he said aspects of the August storm were “consistent with climate change” and that both of the climate studies so far have shown it likely “had its fingerprints” on the disaster.

Coastal areas are seeing flooding increase as rising temperatures push up sea levels, yet houses that flooded in Louisiana last year were miles from coasts and rivers and outside flood zones — a reminder that climate pollution is also raising flood risks inland. Warmer sea temperatures are fueling more frenzied storms. And warmer air the world over means more water can be held in the sky before it bursts down as rain, hail and snow.

A threat to Louisiana’s spirit

After losing almost everything to Hurricane Katrina, Shantel Smith and her family have lost almost everything again. For several days after the storm eased, they stayed with a relative while waters receded. They saw one of their houses in a photo on Facebook, only its roof peeking above the water.

Shantel Smith and her 11-year-old son, Gabriel, stand in front of the house in north Baton Rouge they’re renting while their own flood-damaged house is repaired. Ted Blanco/Climate Central

Smith’s mother is the only family member who has been able to move back home, and her house is still missing cupboards and flooring. Smith and her son are renting a house in suburban north Baton Rouge that’s largely bereft of furniture and appliances while they wait for their own house to be repaired.

“I don’t think the rest of the country is aware of what’s happening in Louisiana,” Smith said. She worries about crime and flooding more than she used to, as well as climate change and the coast, where land is wasting away because of flood control efforts, upstream changes to the Mississippi River, gas and oil industry projects, and rising seas. She fears for Baton Rouge’s future if its communities and neighborhoods don’t heal. “It’s bad here,” she said. “But it could get worse.”

Smith was working as a graphic designer before the flood. Afterward, she had to find new work. A friend gave her résumé to Louisiana Spirit, which offered her a job on an outreach team. The job would involve knocking on doors with a crisis counselor and seeking out survivors at churches and events. She would connect them with groups offering food, mattresses, sheetrock, and other support, and urge them to appeal decisions by federal agencies that had denied them aid.

The work can be cathartic but difficult. Canvassers have been menaced by dogs, swarmed by mosquitoes, and confronted by armed residents. Civic-minded and appreciative of Louisiana Spirit for helping her family recover from Katrina, Smith accepted the position. “I love to help people,” she said. “My family and I went through a lot of counseling with Louisiana Spirit, through their group counseling sessions.”

Louisiana Spirit had been preparing to shift into its second phase of post-disaster operations, when its workers stop canvassing so intensively and begin providing more group counseling to help firefighters, nursing homes residents, schoolchildren, and other survivors and emergency responders cope.

“We try to go in and let them debrief, let them talk about it,” said Nicole Coarsey, the state official coordinating the agency’s response. “We want to make sure that everybody is getting back to some sense of normalcy.”

Instead, Louisiana is preparing to lay off Smith and more than 100 of her colleagues.

FEMA rejected a $16 million request to fund Louisiana Spirit’s counseling services beyond Aug. 25, telling the state in a letter it “failed to adequately justify” the number of survivors that would benefit. A FEMA spokesperson said Louisiana has time to appeal. With mental health at stake, state officials are considering doing so — though their time is stretched as they scramble to contain flood fallout amid a famine of national compassion.