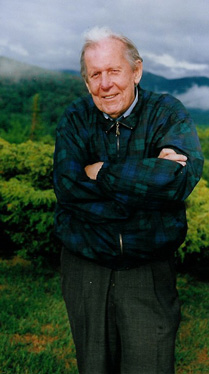

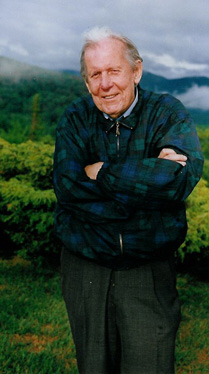

Thomas Berry, a Catholic priest and self-described “Earth scholar,” passed away June 1 in Greensboro, N.C., where he was born in 1914. He was 94 years old.

Thomas Berry, a Catholic priest and self-described “Earth scholar,” passed away June 1 in Greensboro, N.C., where he was born in 1914. He was 94 years old.

A member of the Passionist order that was founded to teach people how to pray, Berry went on to become an influential eco-theologian — though he preferred to call himself a “geologian.” By the age of 8 he had concluded that commercial values were threatening life on Earth, and three years later had an epiphany in a meadow in which he came to understand that the evolution of the universe was for humans the “primary revelation of that ultimate mystery whence all things emerge into being.

Berry entered a monastery at the age of 20 and later went on to earn a doctorate in history from the Catholic University of America. He was deeply influenced by the work of Teilhard de Chardin, a French philosopher and Jesuit priest who developed the concept of the “noosphere” — the realm of human thought comparable to the atmosphere and biosphere. Berry also studied Native American culture and shamanism.

Berry went on to become one of the most profound thinkers in the environmental movement, with his books including “The Dream of the Earth,” “The Universe Story” and “The Great Work” exploring the place where ecology and theology connect.

In 2006, Southern nature writers John Lane and Thomas Rain traveled to Greensboro to talk with Berry about how nature writers can help resolve the current imbalance between humans and the rest of the natural world. Berry was critical of the idea prevalent in among some evangelical Christians that the Bible says that “man shall have dominion over all the land,” noting that a more accurate translation is that “man shall be steward to the land.” He was also critical of some environmentalists, suggesting they lack a deep understanding of how the human mind functions. According to the interview posted on Appalachian Voices’ website:

Humans can be described as “that being in whom the universe reflects on itself in a conscious mode of self-reflection.” We humans actually enable the planet Earth because we are members of the planet Earth. We enable the Earth to reflect on itself. We’re doing a terrible job with what knowledge we have. It’s not that the knowledge is wrong. It’s that we don’t know how to use it. This is one of the basic failures of science. Science does not instruct us on how to use science.

Berry also had a radical notion of rights, believing that it was a mistake to ascribe them only to humans. As he told his interviewers:

This kind of thinking is a disaster! To think that we have certain rights to intrude upon the living things and that the other beings don’t have rights, this is a sacrilege. Every being has rights! Every being has free rights. … The right to be. The right to habitat. And the right to fulfill one’s role in the great community of the cosmos. I don’t see how anybody could argue with these rights. I mean, for humans to think they are the only beings that have rights is just silly. All things get their rights from existence. From merely existing.

Among those whose thinking Berry influenced are David Korten, an outspoken critic of corporate globalization and co-founder of the nonprofit group that publishes YES! magazine, and Wangari Maathai, the founder of Kenya’s Green Belt Movement and the first African woman and environmentalist to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

For information on Berry’s funeral and memorial services, see the Greensboro News & Record’s news obituary. For more on his life and his books, visit Berry’s website.