The forests of the West African nation of Liberia cover almost 12 million acres, and are home to nearly half of Africa’s mammal species — including the region’s largest forest-elephant population. But these forests, and the communities that call them home, have been ravaged by 14 years of brutal civil war. Liberian President Charles Taylor used timber to fund much of that violence, entering into illegal logging contracts with a favored company. Private militias hired by the logging industry exacerbated the country’s already enormous suffering, in some cases destroying entire villages.

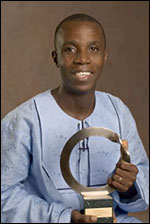

Silas Kpanan’Ayoung Siakor.

Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize.

Silas Kpanan’Ayoung Siakor, the director of the Sustainable Development Institute in Liberia, risked his life to collect evidence of falsified logging records, illegal logging practices, and arms smuggling associated with the timber industry. He gave this evidence to the United Nations Security Council, which imposed an international ban on the export of Liberian timber — part of a series of trade sanctions still in place.

Though Siakor was forced to flee the country in 2003, he returned in 2004, after Taylor’s ouster, and is working with the country’s new leadership on national timber policy reform. Liberia’s current president, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, has cancelled all of the country’s timber concessions, and has said that new contracts will not be issued until reforms are in place.

Siakor, 36, was awarded one of six 2006 Goldman Environmental Prizes at a ceremony in San Francisco on April 24. He spoke to Grist from San Francisco.

How did you first become aware of the illegal logging taking place in Liberia?

Back in 2000, when I started work on these issues, I was primarily working on my organization’s newsletter. Part of my responsibility was to go out into the field and try to get an understanding of what the situation was like, what the logging activities were like. The more I went out and talked with people, and saw logging actually taking place, the more I was drawn to the issue. So in 2001, I began to work full-time on logging.

How did you discover and expose the link between illegal logging and civil war in Liberia?

It was public knowledge within Liberia at the time. All we did was pull the information together, organize it, and present it to [NGOs] and influential policymakers who were working outside of Liberia. That paved the way for more dialogue and more discussion of these issues.

What made you personally decide to take action?

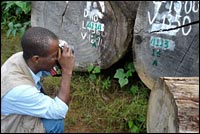

Photographing logs being salvaged by ANA Wood in Rivercess, Liberia.

Photos: Courtesy of Silas Siakor.

As I went out more and more to talk with people, their stories were just very disheartening, traumatic in a way. I talked to villagers whose houses had been destroyed by logging companies in order to build roads through their villages, women who had been harassed and intimidated by militias belonging to those companies, and individuals who had been arrested and detained by the different militias belonging to the companies. So it kind of challenged us to ask ourselves, “What can we do to change this situation?” Even though it was a fairly difficult thing to do, we felt somebody had to do it.

It sounds extraordinarily dangerous. What gave you the courage to take such enormous risks?

When you experience the level of poverty, the level of humiliation, the widespread human-rights abuses that are being perpetrated against these people, it makes it really difficult to turn back, in spite of the risks associated with trying to bring the issue up. So we saw it as a calling, in a way. We felt we had to stand up and say, “This isn’t right, this has to stop.”

Were you or your allies threatened directly?

In our everyday work, we had to live with the fear that when [the information we were gathering] became public knowledge within Liberia, it would have very serious implications. That fear was always there. When we published our report in September 2002, that brought the issue to the forefront. Once, when [Taylor] granted a radio interview, he went off track and made very threatening comments about our work. He said that if he were ever so fortunate to lay hands on the individuals who published that report, their families would have to mourn their loss. The words he used were that their families “would have to wear black,” which in typical Liberian parlance means that that person will be killed. The president himself said this.

A couple of weeks later, the Senate summoned us to explain the motive behind the preparation of the report — not to discuss the content, or the issues we were raising, just our motives. They were very, very harsh in their response, and the debate in the Senate was characterized by a lot of very threatening comments by different senators.

Most of the opinion leaders that we talked with at that time said it wasn’t really safe to go forward and play hero. So I left the country in 2003, and stayed away until 2004.

If you had stayed, do you think you would have been harmed?

There was no question about that whatsoever. Just listening to the comments that were thrown across the floor by the Senate, just getting a feel for the intensity of debate, the level of comments being made, there is no doubt in my mind what would have happened. Some of those who dared to challenge the system in the past actually lost their lives. Some of them went to jail. So I can only imagine what would have happened to me if I had stayed.

Where did you go when you left?

I had to go hang out in Sierra Leone, which ironically was one of the countries deeply affected by Taylor’s war activities in Liberia. After a while, I moved on to Cote d’Ivoire — and then Cote d’Ivoire became embroiled in a conflict, which was again promoted by Charles Taylor. So I was just running around in the West African subregion. My family was still back in Liberia, so day in and day out I had to just think about them, and stay in telephone contact with them. They laid low and things went OK, and we are all very happy that we can be together again.

What do you consider your greatest victories so far?

All that has happened as a result of this work is a very, very powerful indication that when there is something wrong in your community, you can make a difference by standing up.

Siakor trains a team to document illegal timber.

Two of the logging barons that were very involved with Charles Taylor and the timber-for-arms trade are in jail now. One is standing trial in The Hague for crimes against humanity, and for violating international law and the United Nations arms embargo on Liberia. Charles Taylor himself is personally behind bars, and will be standing trial in the next couple of months. All the timber companies have lost their concessions — as we speak, no timber company has any claim whatsoever to an inch of Liberian territory.

When I look back, I think that all of these things, in many different ways, carry their own significance for me.

What has the election of President Johnson-Sirleaf meant for your work?

She has made some very positive moves. She has acted very boldly to cancel all [timber] concessions, at our insistence. She has put together a committee to look at the industry in a holistic manner, and come up with a blueprint for how things can be turned around for the benefit of the country. For the first time, we have been asked by the government to play a very active role in that entire process.

We are kind of cautious at this point, staying aware of the fact that she is a politician, and most of the time political agenda or interests can override the environment and human rights. We are giving her the benefit of the doubt, but we are very conscious that we have to stand firm and maintain our position on some of the critical issues.

What does this prize mean to you?

To be quite honest, I haven’t really come to terms with the fact that I’ve been awarded this prize [laughs]. But it is going to raise the profile of our work in a lot of ways. It is going to add credibility for what we did, for what we stood up for. It tells people that even if what you do doesn’t appear to be that big, a lot of people can value it very much. I think it will be a source of inspiration for a lot of people back in Liberia.

What do you plan to do with the money?

I’ve been talking about this a lot with my colleagues, and one thing we’ve agreed on in principle is to use the money to strengthen the communities we are working with — those communities most impacted by the illegal logging activities. We want to work with them to help them find their own feet, their own voices, so that we don’t always have to be there to talk on their behalf.

What do you hope Liberia will be like 10 years from now?

We hope that local communities in the forest region will have a very strong say in how natural resources are managed, particularly the forests on which they depend. We hope for a Liberia in which multinationals, especially those in the timber industry, will do all they can to respect environmental standards, and that their extraction practices will not unnecessarily degrade our forests. We hope for a Liberia in which our culture and traditional practices will be respected by our central government, and by the multinationals that come to extract resources from there.