In 2019, New York State passed a historic law to cut greenhouse gas emissions from every part of its economy. But for some, the most significant part of the legislation was its focus on environmental justice and equity. The law, titled the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, required that 35 to 40 percent of future benefits of state investments in clean energy, energy efficiency, housing, workforce development, transportation, and pollution reductions would have to serve “disadvantaged communities.”

That provision was modeled on a similar program in California and later became the template for a national goal called “Justice40,” which President Joe Biden announced when he took office a year ago. But New York — and the federal government, for that matter — can’t be held accountable for that promise until it clears up how the benefits of investments will be measured, and pins down what, exactly, a disadvantaged community is.

While New York state officials worked to clarify the benefits question, a new Climate Justice Working Group, made up of leaders of environmental justice and community organizations from around the state, was tasked with deciding on the criteria to identify disadvantaged communities. After 18 months of deliberation, they have finally arrived at some answers.

In December, Chris Coll, director of the energy affordability and equity program at the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, informed the Climate Justice Working Group how state agencies have decided to measure benefits. The announcement, which was made during the final working group meeting of the year, confirmed what many in the climate justice community had been hoping for: While agencies will keep track of any nonmonetary benefits from climate-related investments, they will only count direct investments — the actual dollar amounts of climate-related spending — toward compliance with the 35 to 40 percent goal.

“This is really great news,” said Elizabeth Yeampierre, the executive director of the New York City-based organization UPROSE and one of the members of the working group, during the meeting. The phrase “benefits of investments” had been a major source of frustration and skepticism for environmental justice advocates because it opened the door for the state to employ all kinds of creative accounting to meet the 35 to 40 percent mandate. “This is rockstar stuff,” Yeampierre said.

At the same meeting, the working group voted unanimously to move forward with its proposal for how to identify disadvantaged communities, or DACs, which will be released for public comment this month and finalized later this year. But just before the vote, members continued to question their own proposal, illustrating the many trade-offs required in whittling down an abstract concept to a practicable policy. The stakes for labeling communities as “disadvantaged” are not only monetary — the definition will also determine where the state prioritizes pollution abatement and greenhouse gas reductions.

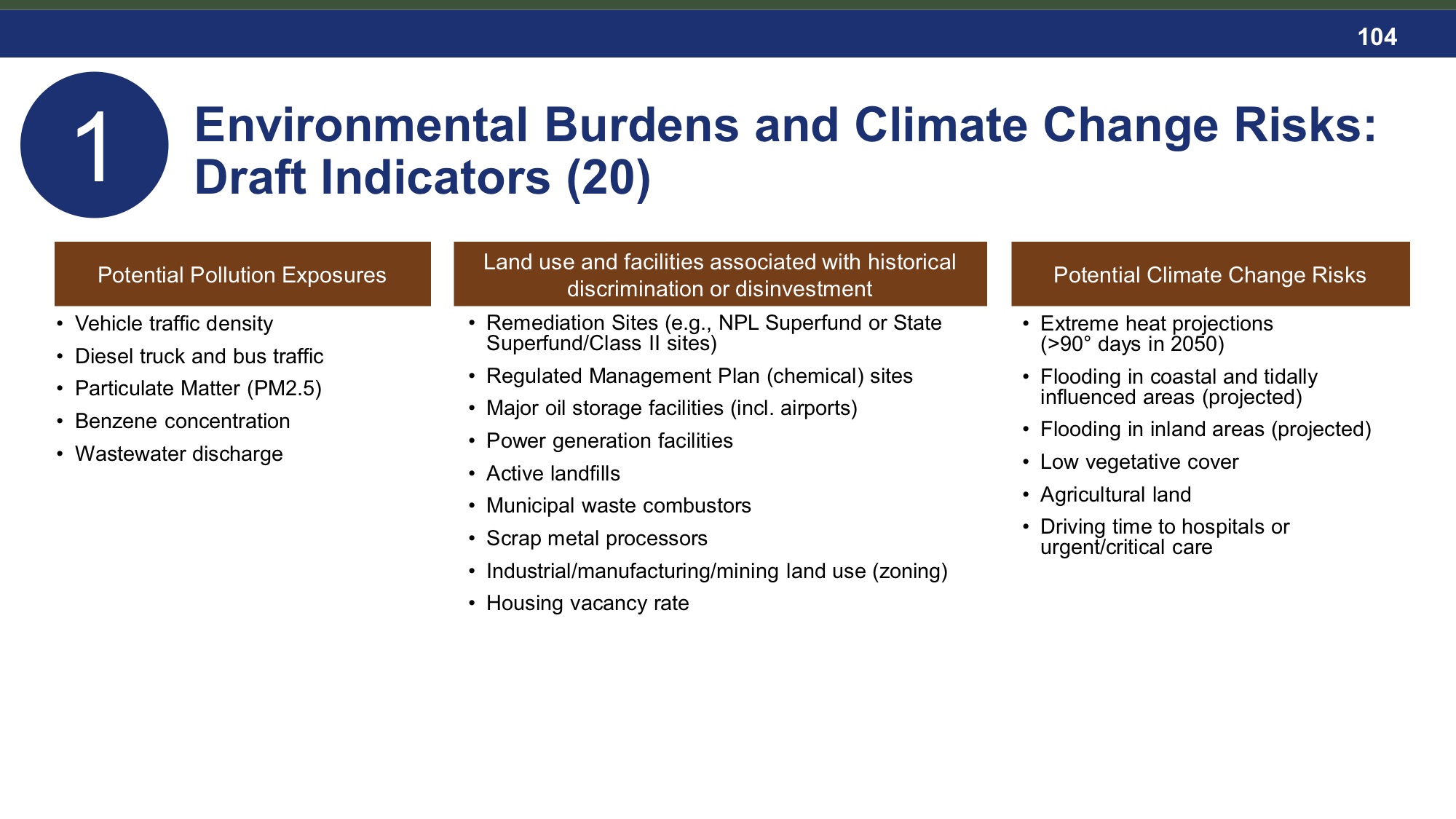

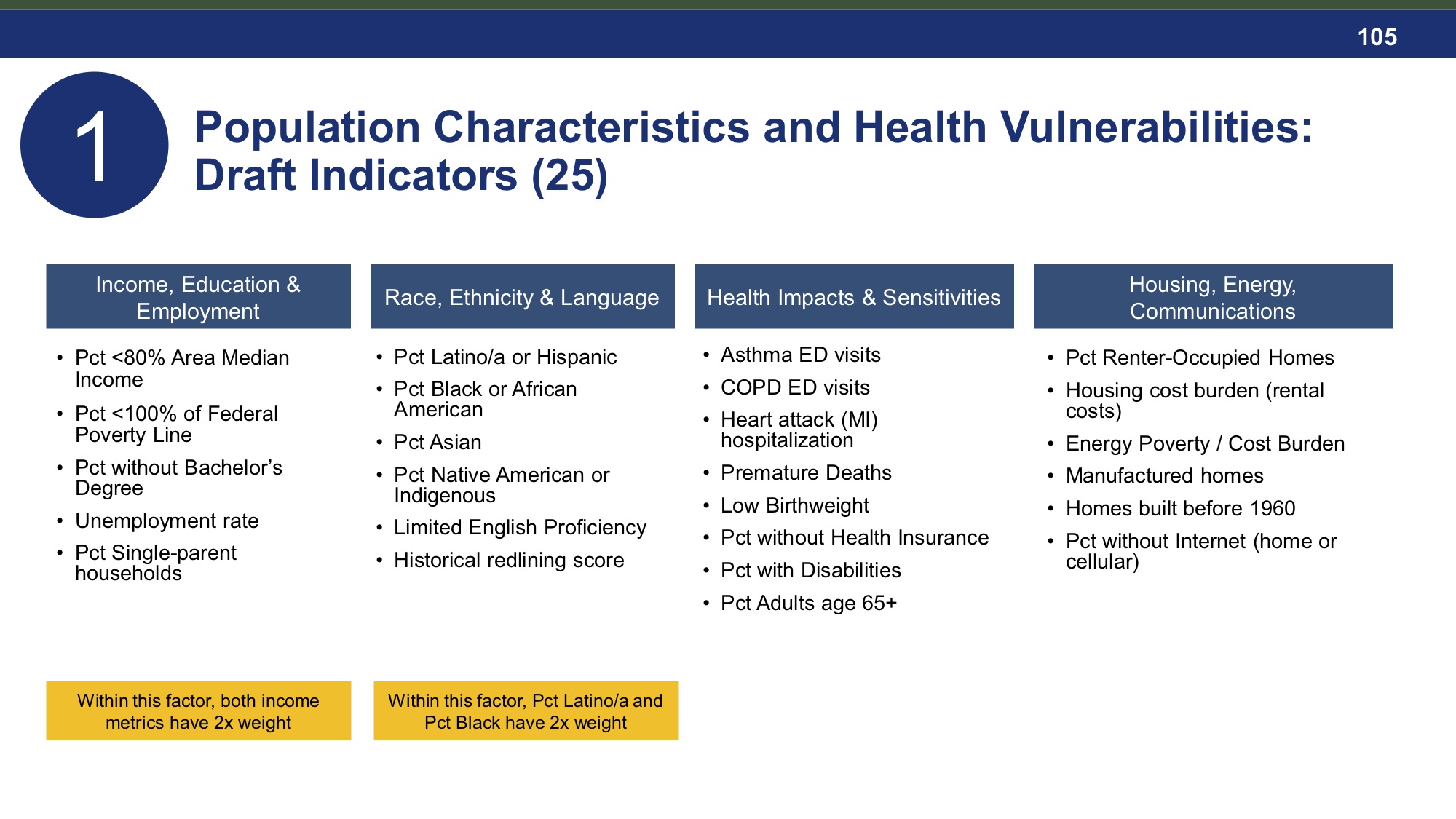

The working group’s project involved creating a new mapping tool that aggregates data about every census tract in the state. While the legislation pointed to broad categories of communities that the definition should include — areas burdened by pollution, areas with high concentrations of low-income residents or people from historically marginalized groups, areas most vulnerable to the effects of climate change — the group still needed to decide what data to draw on to identify those communities. They settled on 45 different “indicators” or datasets that measure things like income, race, unemployment, home ownership, prevalence of asthma, the presence of air pollutants like benzene, proximity to polluting facilities, and potential climate risks like flooding and extreme heat. Based on this data, each census tract is given a score.

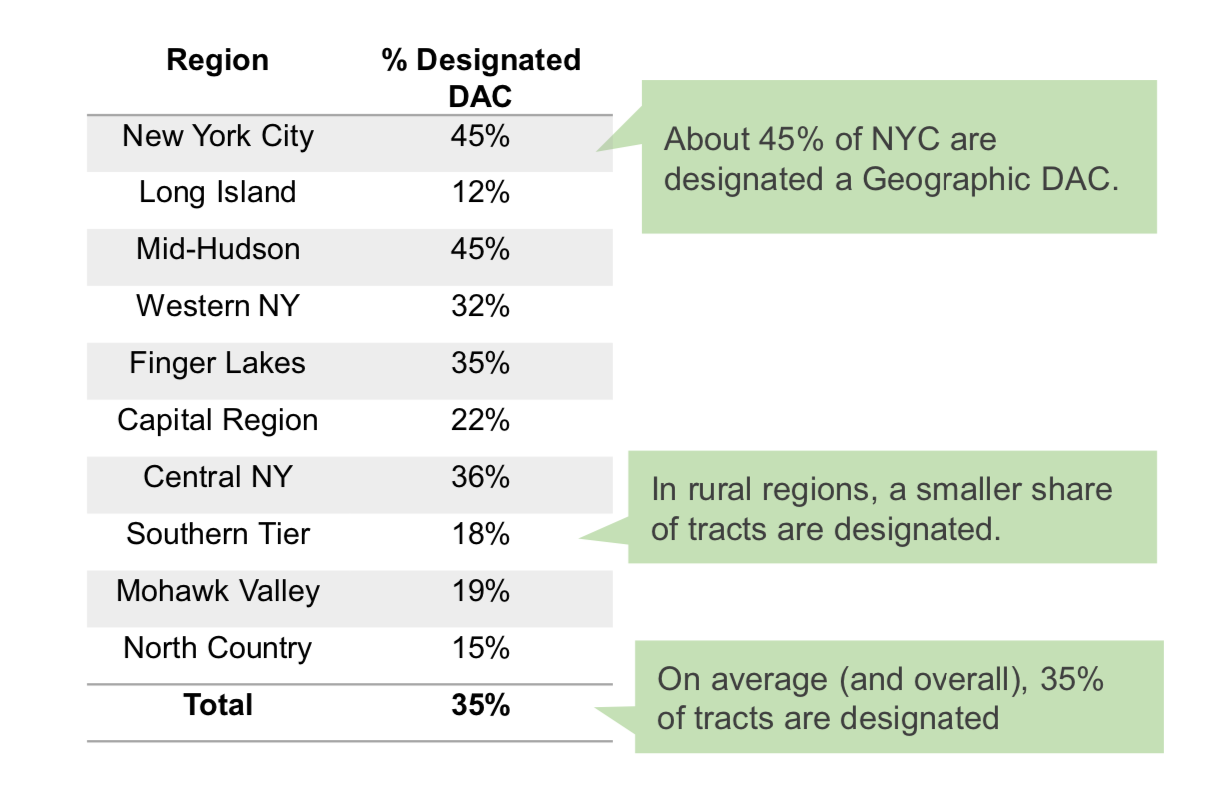

Under the proposed method, the census tracts that score in the top 27 percent statewide, as well as the top 27 percent of non-New York City census tracts, would be designated DACs. This two-part system is meant to ensure an even distribution of benefits throughout the state — otherwise the DACs would be heavily concentrated in New York City. Additionally, officials from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and the Department of Environmental Conservation have proposed including Indigenous populations by automatically designating 19 census tracts that are either reservations or tribally owned land recognized by the state. Overall, this approach would lead to about 35 percent of all households in New York being labeled DACs.

But as the Climate Justice Working Group prepared to vote to approve this method in December, some members were still worried that the system was failing to capture all of the right populations.

For example, Yeampierre was surprised to see that the final list of indicators did not include rates of people with diabetes, who are known to be disproportionately people of color and uniquely at risk during storms. “We saw what happened both in the Gulf South and in Puerto Rico when there were these massive hurricanes, and what happened to people who didn’t have access to the food that they needed and to insulin,” she said at the December meeting.

Neil Muscatiello, an epidemiological director from the Department of Health, explained that diabetes was hard to capture in the Department of Health’s existing datasets, which mainly tracked emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Muscatiello’s team felt that the data was incomplete because some diabetes patients are treated in primary care offices.

Throughout the process, the Climate Justice Working Group has had to wrestle with these kinds of data limitations. Several other indicators they hoped to include, like childhood lead exposure, COVID-19 rates, and heat-related hospitalizations or deaths, had to be dropped because there was simply no reliable statewide or census tract-level data — or no data at all — with which to measure them.

“This is still in draft form, right? We’ve got to put something out there,” Alex Dunn, a consultant hired by the state to guide the process and do much of the behind-the-scenes data wizardry, told the group. “Perfectly imperfect is still very much a reality here.”

Another issue that made several Climate Justice Working Group members feel uneasy was that there were still some communities that felt like they met all the criteria to be designated as DACs but somehow were not. Looking at a map of DAC census tracts in Rochester, Abigail McHugh-Grifa, executive director of the Climate Solutions Accelerator of the Genesee-Finger Lakes Region, was perplexed. Some of the communities that were in the 90th percentile for socioeconomic vulnerability and health risks were not lighting up. “Just looking at the maps and knowing these communities, it just doesn’t feel right,” she said at the December meeting.

This problem was somewhat inevitable, because the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act directs the group to consider socioeconomic and health characteristics as well as environmental burdens. A community could have a high population of low-income residents, people of color, or unemployment, but if it is not in close enough proximity to sources of pollution or climate-related hazards, then it may not earn a high enough score to be designated.

Eddie Bautista, the executive director for the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, encouraged his colleagues to take a step back and remember what their task was. “If what we were hoping was that this law would cover every person of color in New York State, it never was gonna do that,” he said at the meeting. “It was never intended to do that right? This was intended specifically to get at the environmental and climate vulnerabilities of these communities.”

However, the group did decide to work in a partial fix to ensure that investments would be made to address the clean energy needs of lower-income residents, particularly in rural communities. The draft methodology specifies that in addition to the top-scoring census tracts, individual households whose income is less than 60 percent of the state median income will also fall under the DAC umbrella. Taking that amendment into account, about 50 percent of all households in the state will be designated as DACs.

Defining DACs so broadly could open up a tricky can of worms for the state, as devoting 35 to 40 percent of all clean energy investments to half of the state’s households could severely dilute the program’s benefits. But if programs that serve communities and programs that serve individuals are each required to meet the spending goal separately, then the benefits of the investments could be distributed progressively, as intended, rather than regressively.

In response to Grist’s questions about the risks of defining DACs too broadly, a spokesperson for the New York Department of Environmental Conservation said, “As the reporting structure is still being developed, we anticipate being able to disaggregate spending on individual households. Once the DACs definition and criteria is posted publicly soon, we will be providing additional information to help clarify some of these things as well.”

Settling on a process to identify disadvantaged communities is just the first step. State agencies still need to create systems for identifying, measuring, and tracking benefits and investments. A preliminary estimate conducted for illustrative purposes by the New York State Energy Research and Development Agency found that the state issued a total of about $3.2 billion in place-based clean energy and energy efficiency investments in 2021. At that level of statewide funding, the total going to DACs could be a minimum of $1.12 billion per year.

Any day now, New York state will open a 120-day public comment period on the criteria and method for designating communities DACs. New York officials will also release an interactive map that will enable people to see which communities would be designated DACs under the draft criteria and where they rank according to various indicators. The state will also host public information sessions and six public hearings before the working group reconvenes to finalize the process later this year. The working group will review the DAC criteria and consider modifications on an annual basis.

At the federal level, the questions of what “benefits of investments” means and how DACs will be designated are still pending. The Office of Management and Budget is sorting through proposals from 20 different agencies for how they would implement Justice40, and the development of a mapping tool to identify disadvantaged communities has been delayed.

Last week, Brenda Mallory, chair of the Council on Environmental Quality, assured the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, a federal analogue to New York’s working group, that updates would be coming soon.

“We will publish the first annual environmental justice scorecard to provide accountability on Justice40 and other key commitments,” she said.