Copyright 2006 by Bill McKibben. First published in OnEarth, a publication of the Natural Resources Defense Council. Reprinted by permission.

First came the mighty winds, blowing across the Gulf with unprecedented fury, leveling cities and towns, washing away the houses built on sand. Toss in record flooding across the Northeast, and one of the warmest winters humans have known on this continent, and a prolonged and deepening drought in the desert West. For Americans, this has been the year the earth turned biblical. Pharaoh may have faced plagues and frogs and darkness; we got Katrina and Rita and Wilma.

An ecological survival guide?

Photo: iStockphoto

But this was also the year the environmental movement turned biblical — the year when people of faith began in large numbers to join the first rank of those trying to protect creation. The key symbolic moment came in February, when 86 of the country’s leading evangelical scholars and pastors signed on to the Evangelical Climate Initiative, a document that may turn out to be as important in the fight against global warming as any stack of studies and computer models. It made clear, among other things, that even in the evangelical community, “right wing” and “Christian” are not synonyms, and in so doing it may have opened the door to a deeper and more interesting politics than we’ve experienced in the last decade of fierce ideological divide.

That document seemed, to many newspaper readers, to come out of nowhere. But, of course, it was the result of long and patient groundwork from a small corps of people. Understanding that history helps illuminate what the future might hold for this effort. And given that 85 percent of Americans identify themselves as Christian, and that we manage to emit 25 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide — well, the future of Christian environmentalism may have something significant to do with the future of the planet.

In the beginning (say, The Reagan Era), all was darkness. To liberal American Christians, the environment was largely a luxury item, well down on the list below war and poverty. “I remember one Catholic bishop asking me, ‘How come there aren’t any people on those Sierra Club calendars?'” says one of the few religious conservationists of that era. To conservative Christians, environmentalism was a dirty word — it stank of paganism, of interference with the free market, of the sixties. Meanwhile, many environmentalists were more secular than the American norm, and often infected with the notion spread by the historian Lynn White in his famous 1967 essay, “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis,” that Christianity lay at the root of ecological devastation. Everyone, in short, was scared of everyone else.

But there were a few lights starting to shine in that gloom. Calvin DeWitt carried one lantern. A mild-mannered Midwesterner with a Ph.D. in zoology, he helped in 1979 to found the Au Sable Institute in northern Michigan. The institute devotes itself to organizing field courses and conferences that teach ecology, always stressing the Christian notion of stewardship, the idea that, as it says in Genesis, we are to “dress and keep” the fertile earth. To understand what a religious environmental worldview might look like, consider this from one of DeWitt’s early statements: “Creation itself is a complex functioning whole of people, plants, animals, natural systems, physical processes, social structures, and more, all of which are sustained by God’s love and ordered by God’s wisdom. Thus, Au Sable brings together the full range of disciplines — from chemistry to economics to marine biology to theology — that we need if we are to be good stewards of God’s household.” That doesn’t sound too frightening, right?

In DeWitt’s Reformed Church tradition, God has left us two books to read. First, the book of creation, “in which each creature is as a letter of text leading us to know God’s divinity and everlasting power.” And second, the Bible. It’s easy to see how environmentalism connects with the first of these, but it’s taken longer to understand its relevance to the second.

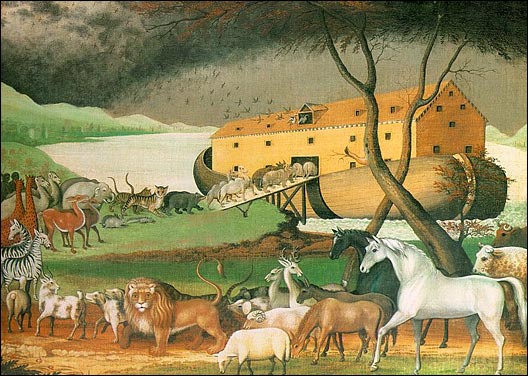

“When we started, for the first two or three or four years almost everything we were dealing with was an Old Testament text, from the Hebrew Bible,” says DeWitt. That makes sense. Since the Old Testament starts at the beginning, it almost has to deal with questions about the relationship between people and land. There’s Noah, the first radical green, saving a breeding pair of everything; there are the Jewish laws mandating a Sabbath for the land every seventh year; there’s the soliloquy at the end of the book of Job, which is both God’s longest speech in the whole Bible and the first and best piece of nature writing in the Western tradition.

Who will save us this time?“Noah’s Ark” by Edward Hicks, 1846But the sparer, more compressed text of the Gospels and Epistles had never been read with an eye to its ecological meaning — in large part because it wasn’t necessary. Medieval Christians, say, weren’t living in a time of planetary peril. But now that we were, people started finding passages like this from Colossians: Jesus “is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation; for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth … all things were created before him and through him.” It may not sound exactly like an Audubon Society mailer, but the insistence on this world as well as the next was important in helping many pastors open up to environmental thinking. Or this, from Revelation, describing the final judgment, when the time would come for rewarding the servants and prophets and “for destroying the destroyers of the earth.” (That’s a little scarier to secular ears, but if you’ve ever sung Handel’s Messiah, the “trumpet shall sound” stuff echoes the same passage.) The point is, once people started looking, the Scriptures started speaking.

Who will save us this time?“Noah’s Ark” by Edward Hicks, 1846But the sparer, more compressed text of the Gospels and Epistles had never been read with an eye to its ecological meaning — in large part because it wasn’t necessary. Medieval Christians, say, weren’t living in a time of planetary peril. But now that we were, people started finding passages like this from Colossians: Jesus “is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation; for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth … all things were created before him and through him.” It may not sound exactly like an Audubon Society mailer, but the insistence on this world as well as the next was important in helping many pastors open up to environmental thinking. Or this, from Revelation, describing the final judgment, when the time would come for rewarding the servants and prophets and “for destroying the destroyers of the earth.” (That’s a little scarier to secular ears, but if you’ve ever sung Handel’s Messiah, the “trumpet shall sound” stuff echoes the same passage.) The point is, once people started looking, the Scriptures started speaking.

Something else happened too: the emergence of climate change as the key question for the environmental movement. On the one hand, confronting global warming made everything harder — environmental groups suddenly found themselves contending with the main engine of our economy. But for many religious environmentalists, heightening the stakes may have made progress easier — this was a cosmological question, one about the ultimate fate of our species, our planet, God’s creation. Unlike, say, clean drinking water, where simple, practical wisdom was enough to offer you an answer, global warming almost demanded a theological response. In that sense, it was like the dawn of the nuclear age. “The magnitude, the comprehensiveness, the totality of the challenge it represents to God’s creation on earth, the profoundly intergenerational nature of the damage that was being done — it became the central axis,” says Paul Gorman.

Gorman is a story in himself. A former speechwriter for Eugene McCarthy, in 1993 he cofounded the National Religious Partnership for the Environment, which, with generous amounts of foundation money, set out to build environmental support among American Jews, Catholics, mainline Protestants (like Methodists and Lutherans), and evangelical Christians. Crucially, it was willing to go slowly enough to build a solid foundation. “It’s not going to be the environmental movement at prayer,” says Gorman, “not about providing more shock troops for the embattled American greens. We have to see the inescapable, thrilling, renewing religious dimension of this challenge.” A thousand Sunday-school curriculums and special liturgies and summer camps later, Gorman’s effort is bearing real fruit. In 2001, for instance, America’s Catholic bishops issued a pastoral statement on the environment, one that fits the question into their long-standing theology of “prudence” and relates it to their centuries of work against hunger and poverty around the world. “If you measure [the change] against the speed with which religious life integrates fundamental new perspectives, then historically it’s been kind of brisk,” says Gorman.

On occasion, the religious environmental movement flared into public view. At the turn of the century, for instance, while spending a year as a fellow at Harvard Divinity School, I helped organize a series of demonstrations outside SUV dealerships in Boston. Before one demonstration with a bunch of mainline clerics, I joined Dan Smith — then the associate pastor of the Hancock United Church of Christ in Lexington, Mass., where I’d grown up — in painting a banner that said “WWJD: What Would Jesus Drive?” The initials were borrowed from evangelical circles, where they stood for What Would Jesus Do? and usually referred to questions of sex or drugs. But we liked the emphasis on personal responsibility — and we guessed that the newspapers might like it too. Guessed correctly, as it turned out, for the sign was splashed across front pages and websites the next day. Within a matter of months, it wound up back in more conservative circles, where the Evangelical Environmental Network, of which DeWitt was a founder, used the slogan as part of a multistate advertising campaign.

Pilgrim’s Progress

Most of the time, though, the progress has been slower, steadier, and less visible. The Evangelical Climate Initiative document, for instance, grew out of a very private retreat for select leaders at a Christian conference center on the Maryland shore, a gathering that included many of the evangelical movement’s luminaries, most of whom had not been deeply involved in environmental issues. The opening remarks came from Sir John Houghton, an English physicist and climate expert who had served as chair of the scientific assessment team for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the group that definitively broke the news that humans were indeed heating the planet. Sir John was also a lifelong British evangelical (on a continent where Christians are less politically polarized) and a friend of John Stott, another Brit and a beloved elder statesman in evangelical circles. Sir John also could point to his collaborations with business leaders in Europe, like John Browne, chair of BP, who were far more open to acknowledging global warming than were their American counterparts at companies like Exxon.

“When John Houghton speaks, he speaks with both biblical authority and scientific authority,” says DeWitt. “The critic, the detractor, the naysayer has to deal with a person who is both the scientist and the evangelical scholar in one and the same person. As an evangelical, Bible-believing, God-fearing Christian as well as a scientist, he’d made sure that the IPCC reports were absolutely the best and most truthfully stated documents ever produced in science.” And, he adds, “It helps that he’s got a British accent.”

By the conference’s close, the participants had made a covenant to address the issue, and then spent months gathering signatures. When it was eventually released, some leaders of the Christian right, like Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and James Dobson, demanded that it be retracted. Climate science was unsettled, they said. Speaking anonymously, one conservative Christian lobbyist scoffed to a reporter, “Is God really going to let the earth burn up?” The National Association of Evangelicals, the umbrella group for the entire movement, feared a split and stayed officially neutral. But the bulk of the 86 signers (who included seminary presidents, charity directors, and prominent pastors like Rick Warren, author of The Purpose-Driven Life) held strong, some of them quietly relishing the chance to say that their movement was larger than high-profile televangelists and not necessarily a steady date of the GOP. “The grace of it!” says Gorman. “I think you could say this is one of the first significant events of the post-Bush era.”

It’s had legs, too. This spring The New Republic reported that in Pennsylvania the incumbent Republican senator Rick Santorum has come under religious fire for his stand on climate change. At a panel on the subject, a biology professor at Messiah College in Grantham, Penn., “tore into the senator, accusing him of selling out the environment to business interests.” In the words of Richard Cizik, the chief lobbyist for evangelical causes in Washington, “there’s going to be a lot of political reconsideration on this in the coming year. The old fault lines are no more.”

Other evangelicals are less political, but at least as subversive. A former emergency room doctor named Matthew Sleeth, for instance, quit his job to preach the green gospel and says the reaction has been far greater than he could have guessed. His book Serve God, Save the Planet was published this past spring, and he has been traveling to churches ever since. Everywhere his message is the same: God asks us to surrender some of our earth-wrecking wealth. “Bible-believing Christians have confused the kingdom of heaven with capitalism and consumerism,” Sleeth says. He’s not attracted to electoral politics. Instead he’s been downsizing his life — putting up the clothesline, selling his stuff, buying a Prius. (He writes his books on a lifetime supply of old computer paper he rescued from a Dumpster.) The ecological battles ahead of us compare to the greatest battles in American history, he says, and his models include people like the abolitionist John Brown, who practiced exactly what he preached, sharing his farm with freed slaves. “There’s a longing for a spiritual life in this country,” he says, over and over. “A great hunger for something more than capitalism.”

As Faith Would Have It

It’s far from clear, however, that faith communities will take this fight as far as it needs to go. Simply breaking ranks with the Bush administration on this issue took enormous courage for evangelical leaders. So if some legislator offers any kind of deal to “fix” the problem of global warming, it may win all-too-easy endorsement. Some kind of Kyoto-lite measure, like the one proposed by Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Joe Lieberman (D-Conn.), might pass the Congress in the next few years. If it does, the bar has been set so low that environmentalists of all stripes, but especially those out on a limb like the evangelicals, might well sign on, even though the steadily worsening scientific findings make it very clear that bold and rapid action is required.

Here’s Houghton, speaking hard words to Americans: “You’ve got to cut your own greenhouse-gas emissions, on the fastest time scale you can possibly do. You’ve got to help China and India develop in ways that are environmentally friendly and don’t emit too much, but allow them to develop at the same time.” Those are precisely the fights — over scale, speed, and international equity — that will bedevil whatever steps we take to fight global warming, and it’s not clear that the faithful are really girded for the fight. “Will this groundswell have the real moral edge to keep the pressure on over the long haul?” asks Gorman, and he doesn’t answer his own question.

If the answer is going to be yes, a couple of things may need to happen. One, the mainline Protestant denominations will have to step up to the plate. They long ago passed all the proper resolutions decrying the destruction of creation, and certain congregations have launched interesting initiatives. (An upstart group called Episcopal Power and Light, for instance, pioneered the practice of supplying congregations with green power.) But not many mainline Protestants have stepped far outside their comfort zones — in part because the denominations themselves are dwindling in number and beset by internal divisions over questions like the ordination of gay clergy. Still, there are increasing hints of future activism: Planning for possible widespread nonviolent civil disobedience to draw attention to global warming, for instance, was widely discussed at a recent National Council of Churches meeting in storm-wrecked New Orleans. Protests at Ford headquarters? Blocking the entrance to the EPA? Sitting on the tracks of coal trains? Whatever the strategy, it will play better on TV if there are some clerical collars near the front.

The critique from all quarters will need to get sharper too. DeWitt pulls no punches: “We’ve spiritualized the devil,” he says. “But when Exxon is funding think tanks to basically confuse the lessons that we’re getting from this great book of creation, that’s devilish work. We find ourselves praying to God to protect us from the wiles of the devil, but we can’t see him when he’s staring us in the face.”

Much of the uncertainty about the future of such efforts stems from this: Christianity in America has grown very comfortable with the hyperindividualism of our consumer lives. In one recent poll, three-quarters of Christians said they thought the phrase “God helps those who help themselves” came from the Bible, when in fact it derives from Aesop via Ben Franklin and expresses almost the exact opposite of the Gospel injunction to “love your neighbor as yourself.” Says DeWitt, “By accommodating to a new philosophy about how society works, we’ve flipped Matthew 6:33 on its head. Instead of ‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God and all the rest shall be added unto you,’ we’re looking out for No. 1.” Which makes it a lot harder for politicians to start talking about carbon taxes or other measures that might actually start to bring our emissions under control.

Still, there are continuing signs of progress — what Christians might call evidence of the Holy Spirit at work. In August, after the hottest early summer on record in the United States, even Pat Robertson announced his conversion — people were heating the planet, he said, and something needed to be done. In the end, it’s clear that this battle is not only for the preservation of creation. In certain ways, it offers the chance for American Christianity to rescue itself from the smothering embrace of a culture fixated on economic growth, on individual abundance. A new chance to emerge as the countercultural force that the Gospels clearly envisioned. And also a chance to heal at least a few of the splits in American Christianity. Fighting over creation versus evolution, for instance, seems a little less crucial in an era when de-creation has become the real challenge.