The greatest threat to life on earth finally got the attention it deserved on Wednesday as CNN devoted seven whole hours to interviewing presidential candidates for its Climate Crisis Town Hall. It started with Julián Castro, the former mayor of San Antonio, at 5 p.m. Eastern time and ended with Senator Cory Booker from New Jersey, who walked onto the set after 11 p.m. In all, 10 candidates fielded queries from CNN hosts, a studio audience, and questioners on video.

It wasn’t the climate debate that activists — and even several of the candidates themselves — had demanded the Democratic National Committee hold. But it was nearly a full work day packed with climate policy conversation, follow-up questions, and almost no crosstalk. If you were looking for substance over soundbites, this was exactly the forum of your dreams, with each candidate getting more than a half hour to sketch out their vision for climate action.

If you were unable to catch it all, Grist has you covered. Our writers and editors assembled this handy recap of the each candidate’s appearance right here.

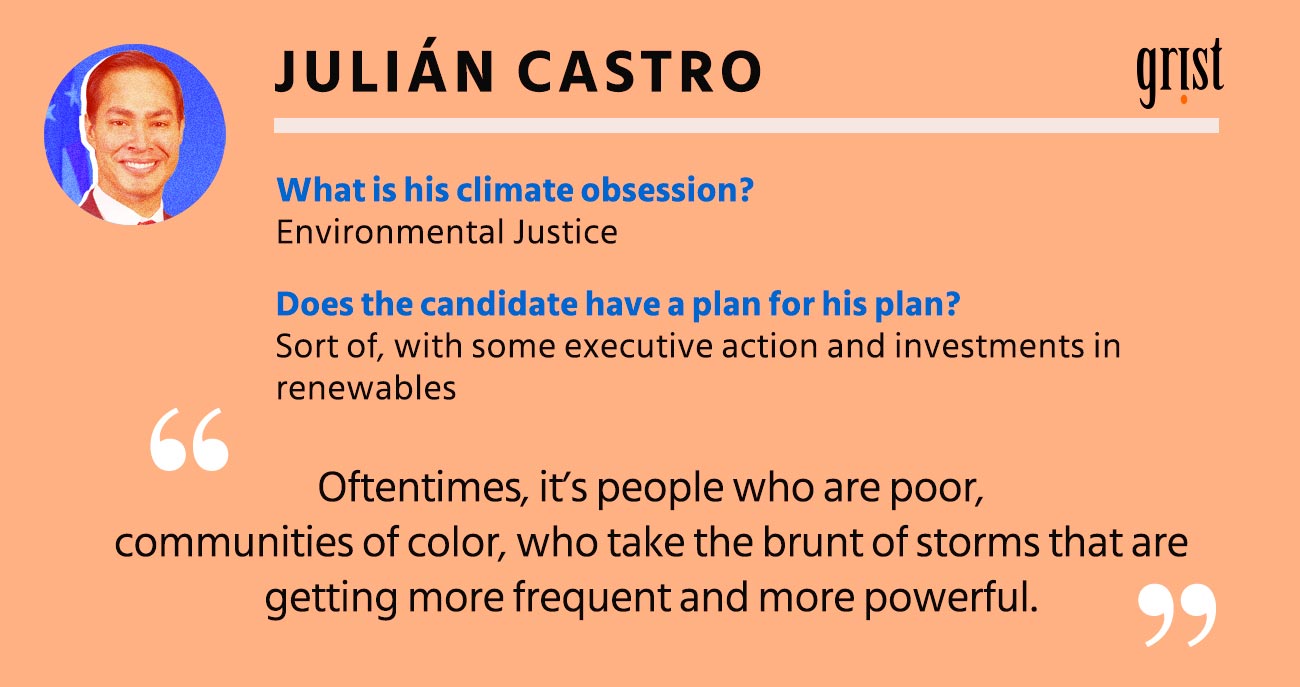

Julián Castro

Throughout the course of his 40-minute time slot, Castro hammered the theme of environmental justice — the fair treatment of communities most vulnerable to pollution and climate change. Questions about disaster relief, keeping polluters accountable, and public lands all led back to Castro’s main focus: justice. “We need to connect the dots,” he said, “both for our benefit and our wildlife’s benefit, to combat climate change.”

But Castro caught flack from a climate activist from the Sunrise Movement in the audience for “welcom[ing] the fracking boom” during his tenure as mayor of San Antonio. “She’s right,” Castro replied. Even so, Castro said he would not ban fracking outright. “What I am doing,” he said, “is moving us away from fracking and natural gas and investing in wind energy, solar energy, other renewables.”

Castro has released two components of his climate platform — an animal welfare and extinction plan and a $10 trillion investment plan — thus far, with more to come.

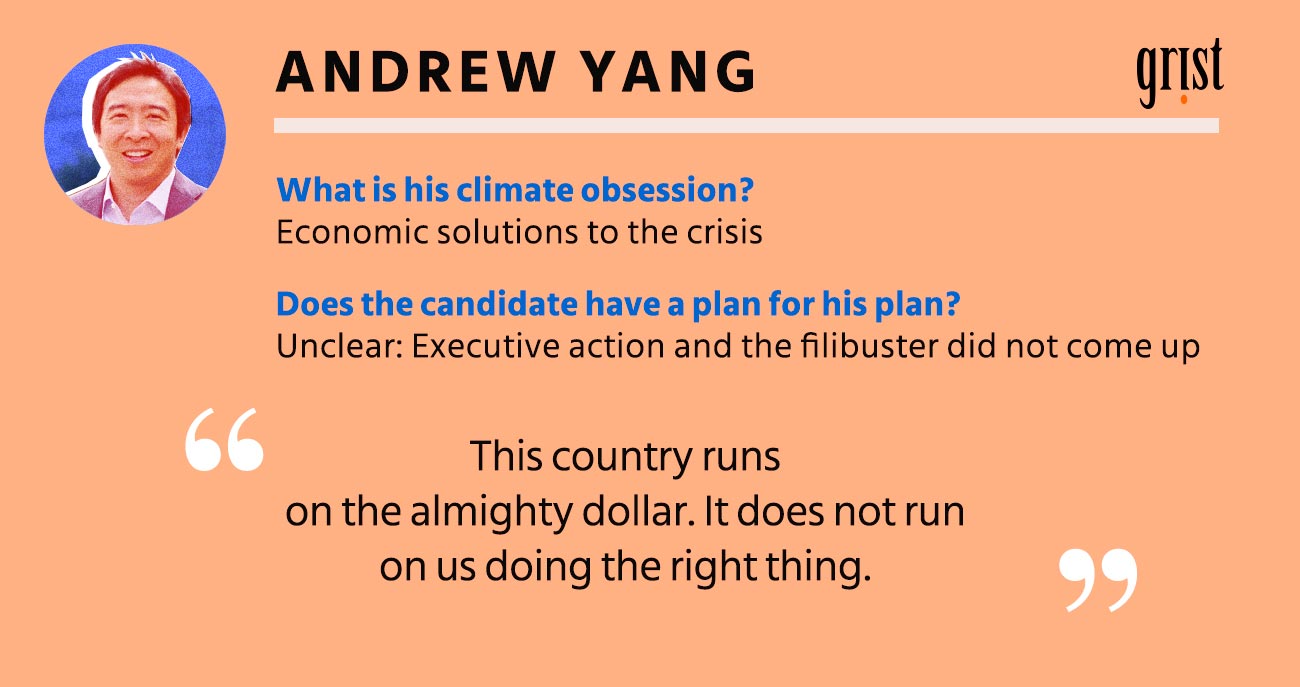

Andrew Yang

Yang’s time onstage featured a buffet of his signature conversational style, wry humor, and economics professor-style climate solutions. “This country runs on the almighty dollar,” he quipped. “It does not run on us doing the right thing.” In addition to promoting his signature “freedom dividends” and “democracy dollars” plans to give Americans cash to get money out of politics, Yang said that he’d redefine the way our government measures economic success, moving away from using gross domestic product as a benchmark and incorporating things like clean air and water into the equation.

“Replacing pipes is expensive … are you kidding me?” he said in reference to cities being hesitant to replace their lead pipes. “You know what’s expensive? Poisoning our kids!”

When asked if he would force people to become vegetarian or drive electric cars, Yang responded that you can’t force anyone to do anything in this country (but added that electric cars are “awesome.”) But he said that solutions of all sorts are needed to tackle warming. He ticked off elements of his climate plan, including pitching thorium nuclear power as a viable alternative to uranium and debating the merits of geoengineering. Yang has been criticized by some for his “pie-in-the-sky” ideas, like using giant space mirrors to reflect warming light from the sun back out into space. When Wolf Blitzer brought up space mirrors though, Yang clarified that geoengineering solutions are “not the main approach at all.” “We’re here because we know this is a crisis,” Yang said. “And in a crisis all solutions need to be on the table.”

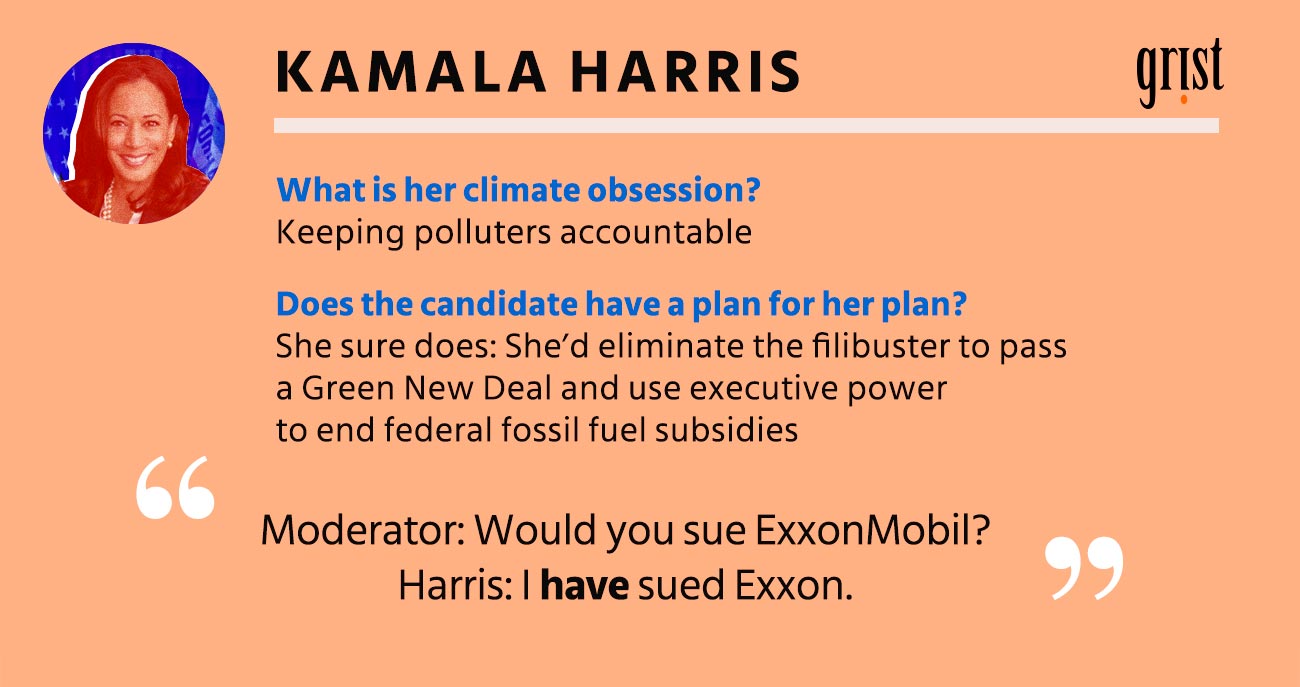

Kamala Harris

The senator from California, who initially declined an invitation to the night’s event, spent a good chunk of her time slot talking about how she would hold powerful polluters accountable. Harris, a former prosecutor and self-described “career law enforcement official,” said she would take companies like Exxon Mobil to court. In fact, she noted, she already has!

Harris is the only candidate to say she will ratify the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol (which focuses on capping super-warming hydrofluorocarbons) on day one in the White House. She also announced she’d support eliminating the filibuster if Congress won’t pass a Green New Deal — something only Elizabeth Warren and (the gone but not forgotten) Jay Inslee backed. And in perhaps the most relatable moment of the night thus far, Harris said she’s not exactly a fan of paper straws (too bendy), but would support making moves to ban plastic ones (as well as supporting incentives to move away from single-use plastic). And even though she loves beef, Harris would encourage implementing new dietary guidelines to reduce consumption of red meat.

Amy Klobuchar

One of only two high-profile Midwesterners in the race, the senator from Minnesota has bona fides over other candidates when it comes to the role rural America can play in mitigating the climate crisis. Klobuchar leaned hard on that credential. “It’s important to bring it home when we talk about this,” she said. “And when I talk about home, for me, I mean the middle of the country.”

When asked how she would get the country running on green energy, Klobuchar took a practical turn. “We have to do things that we can do without Congress, legally.” Her to do list: Day 1, rejoin Paris. Day 2, bring back the Obama-era Clean Power Plan. Day 3, reinstate Obama’s fuel efficiency standards for vehicles. “On day 7, you’re supposed to rest, but I don’t think I’m going to do that,” she quipped.

Klobuchar unveiled a $1 trillion platform on Sunday, a proposal that’s roughly a tenth of the size of some of those introduced by her opponents. Much like Castro, Klobuchar was grilled on her position on phasing out fossil fuel production. She answered with her customary pragmatism. “I don’t think we can phase it out in a few years,” she said. “You have to do it over a period of time and do it in a way that keeps our economy going and our economy strong.”

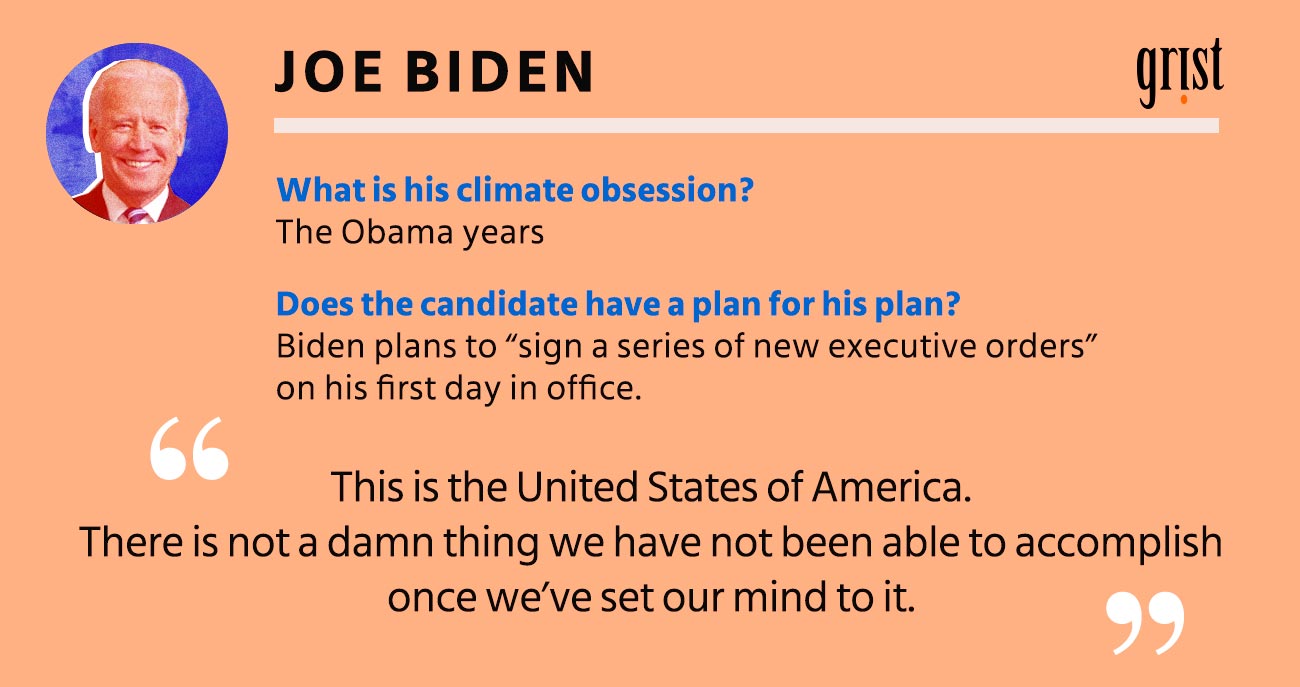

Joe Biden

Biden came out swinging and was never really able to dial back his defensive tone (at one point, he said “I know that” when Anderson Cooper explained what Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale is to the audience). He referenced his work under Barack Obama often, effectively using the former president as a human shield at some points. He cited his record far more often than his climate plan, and seemed to perform best when spouting cliches about the can-do American spirit.

He stumbled into trouble early on when an audience member asked why, though Biden had signed the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge, the former Vice President was holding a campaign fundraiser hosted by Andrew Goldman, a co-founder of the natural gas company Western LNG. “I didn’t realize he does that,” Biden replied. (Cooper later clarified that Goldman doesn’t work at Western LNG.) Biden then touted how open he is to scrutiny. “Every one of my fundraisers has been open to the press from the beginning,” he said

Biden spent much of his time discussing the need for America to lead the world on climate change solutions — even though he pointed out more than once that the U.S. is only responsible for 15 percent of global emissions. Still he noted that America can’t tackle climate change alone. Biden was finally able to find his feet a little when asked about how he’d get China to lower its emissions. “They’re making the environment much, much worse,” he said, “so there has to be a price that they pay.” That’s why he thinks it’s important that the U.S. reenter the Paris Agreement — so it can hold China and other polluters accountable.“You can’t very well preach to the choir if you can’t sing,” he said.

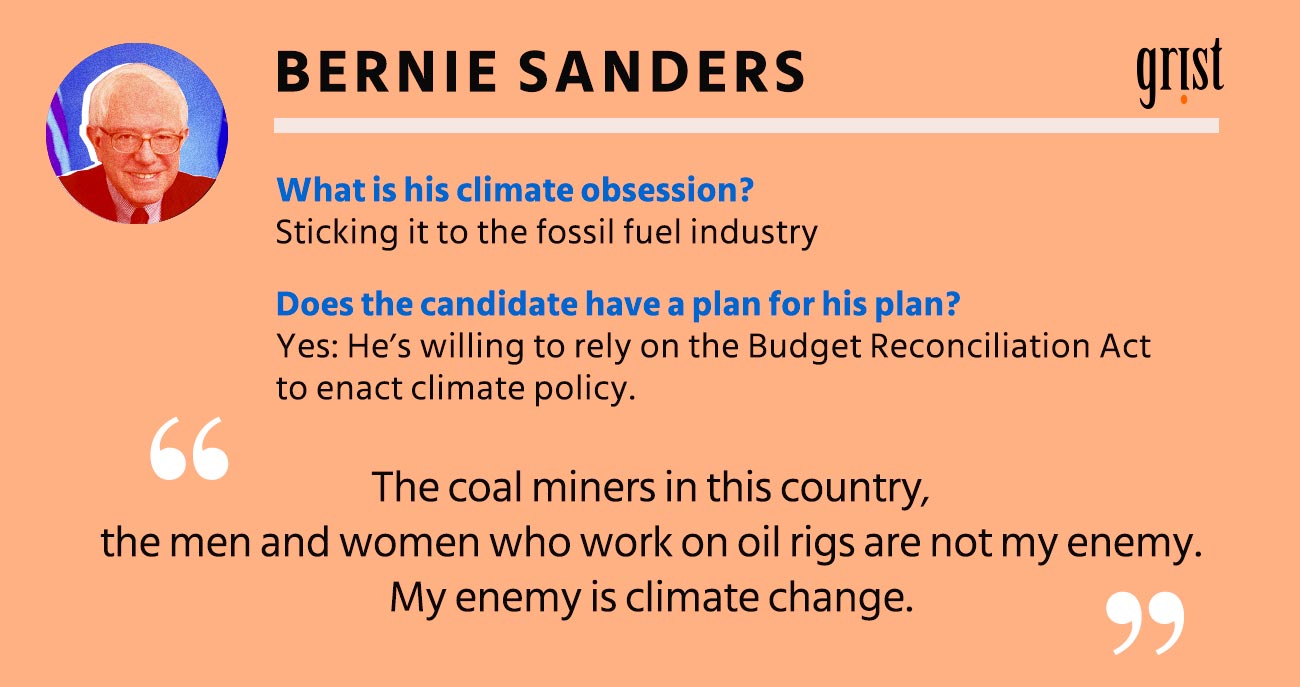

Bernie Sanders

The senator from Vermont may very well be stepping into Jay Inslee’s shoes as the “climate candidate.” Last month, Sanders announced the most ambitious climate plan yet among the candidates, a $16.3 trillion package that factors climate change “into virtually every area of policy.” The first set of questions aimed at Sanders dug into his plan’s hefty price tag, which he said would be funded by diverting subsidies over a 15-year period, making cuts to military spending, and collecting tax revenue from new jobs created by his plan.

When asked how to transition workers away from jobs in the fossil fuel industry, Sanders touted his labor bona fides. “The coal miners in this country, the men and women who work on oil rigs are not my enemy,” he said. “My enemy is climate change.” He pointed out his climate plan would not leave fossil fuel workers behind: It would guarantee people who lose their job in fossil fuels an income for 5 years, plus new job training.

In a moment of levity, when asked whether he would reverse Trump’s energy-efficient lightbulb rollback, Sanders gave the shortest answer of the night: “Duhhh!”

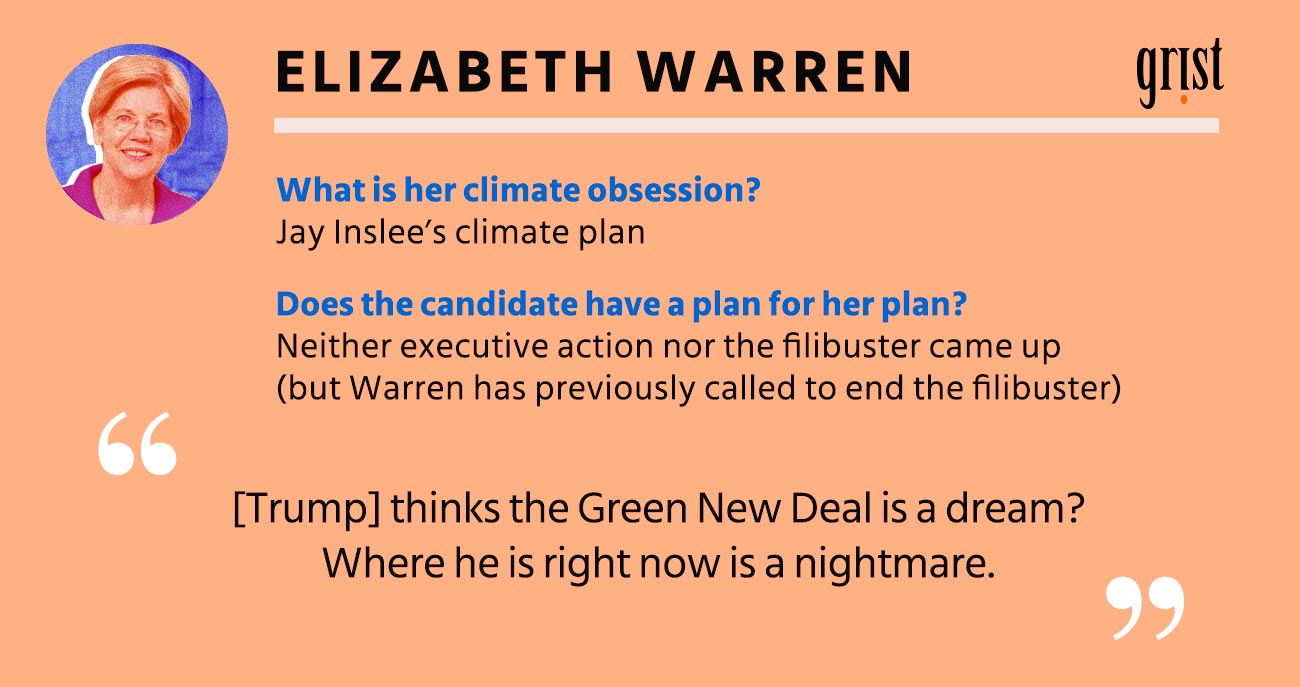

Elizabeth Warren

Warren was the first candidate in the Democratic primary to release a climate plan: a public lands bill in April. Since then, she has released four more climate-themed plans. Her latest plan pulls directly from the climate platform bequeathed to the Democratic field by Inslee. At the town hall, the Massachusetts senator pulled out her signature move — drilling into policy details.

“I want to talk about change and the way we think about change,” she said. “Let’s put in place some real rules.” In addition to putting a price on carbon as a way to hold polluters accountable, Warren wants to eliminate emissions from buildings, cars, and the electricity sector by 2028, 2030, and 2035, respectively. She also suggested leveraging a “climate adjustment” tax on goods imported from countries that are not in compliance with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

When asked about Trump’s recent effort to roll back standards for energy efficiency lightbulbs, Warren made it clear she thought the question was a bit of a distraction: “Oh, give me a break,” she said. The problem isn’t lightbulbs or straws or burgers, according to Warren; it’s big polluters. In other words, lightbulbs shmightbulbs, let’s go after the fossil fuel industry.

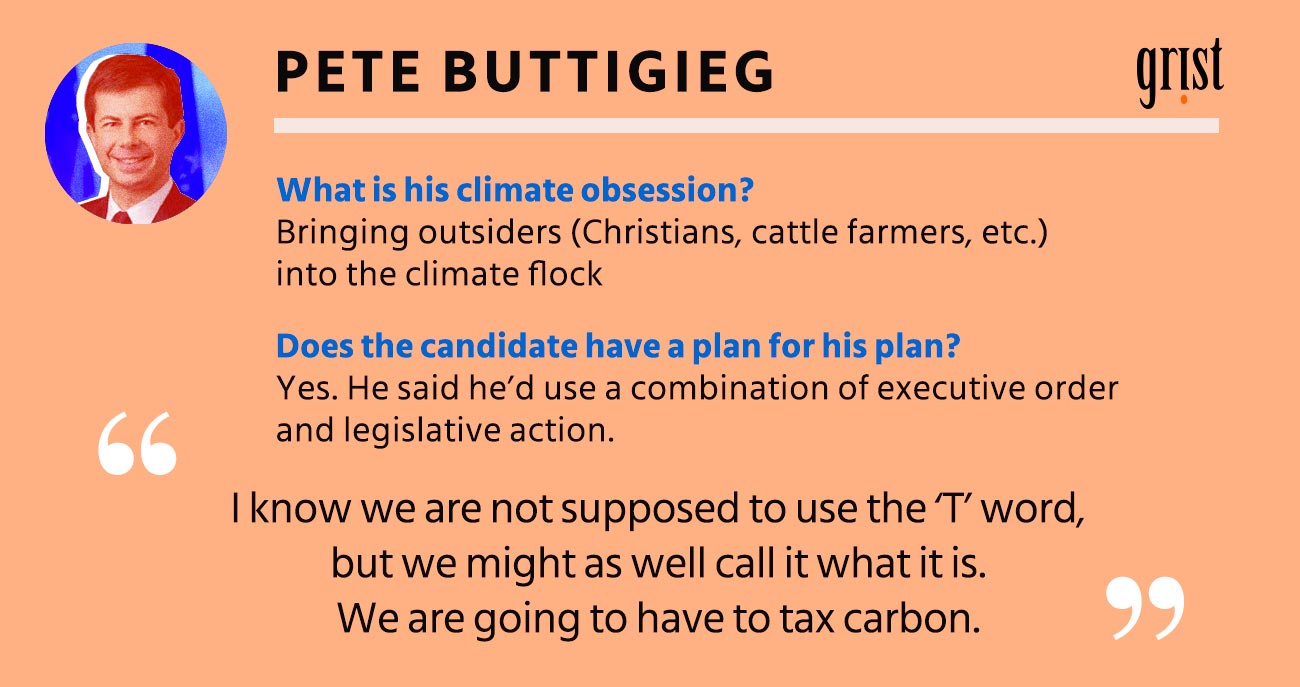

Pete Buttigieg

South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg spent his time on stage emphasizing bipartisan-friendly ideas to tackle global warming and making a moral argument for why climate action is necessary. He focused in on farming, soil, and the American Heartland, as has been his forte in the campaign thus far.

He also differentiated himself from other candidates by adding a religious argument for environmental action: “If you believe that God is watching as poison is being belched into the air we breathe … what do you think God thinks of that?” he asked at one point. “I bet he thinks it’s messed up!” Buttigieg went on to call pollution “a kind of sin,” and suggested one questioner in the audience have “coffee after church” with other rural folks to explain how they can gain jobs and benefit from being part of the solution.

Buttigieg said he’d use a combination of executive and legislative action to implement his plan — which includes a carbon tax — but didn’t offer many specifics as to how he’d garner the bipartisan support he values so much. “We’ve been wrangling over plans for my entire lifetime,” he said at one point, like a reference to him being the youngest presidential candidate.

“This isn’t just saving the planet,” he said. “It’s about saving the future.

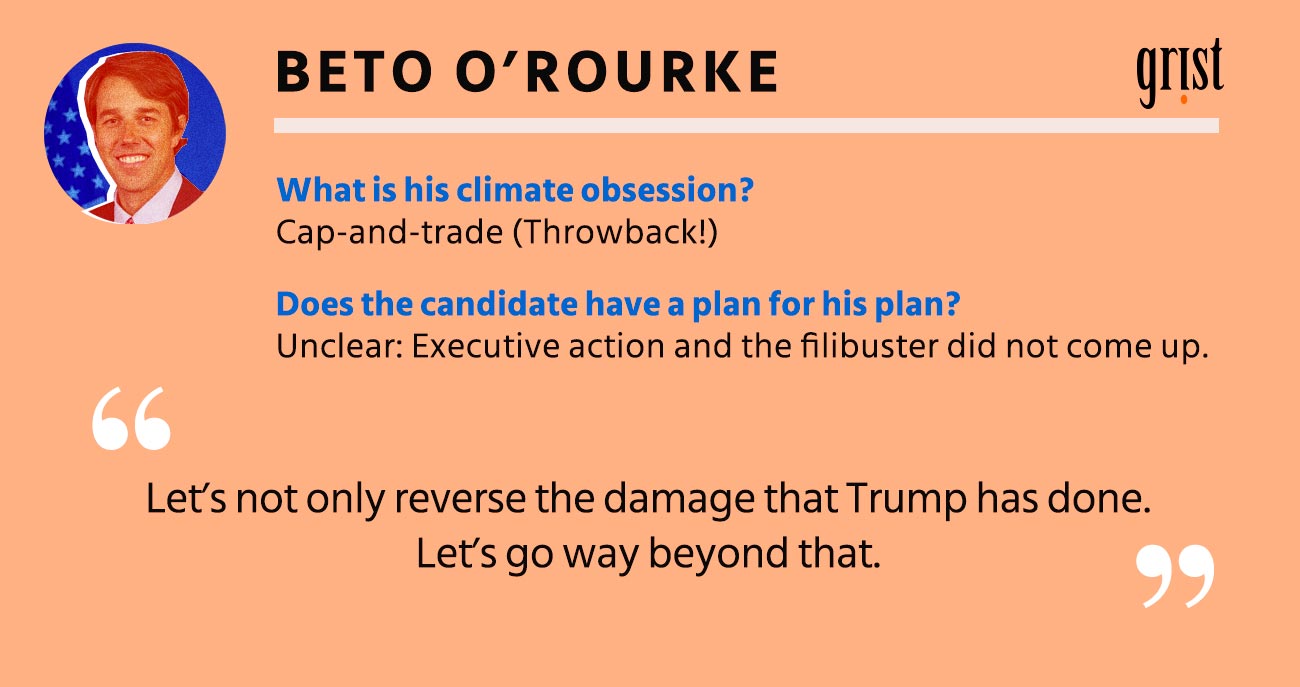

Beto O’Rourke

Beto “I-convinced-my-mom-to-vote-for-me” O’Rourke has repeatedly called climate change “the greatest threat the nation faces.” He released a sweeping $5 trillion climate plan as his first major policy rollout way back in April (as he reminded viewers several times during the town hall). Wednesday night, the former Texas representative emphasized he wouldn’t support a carbon tax, and that he thinks the best possible way to put a price on carbon is through a cap-and-trade system. Like Castro, O’Rourke said he would create a new refugee category for those fleeing the effects of climate change.

O’Rourke hearkened back to his Texas roots as he fielded questions from CNN’s Don Lemon and the town hall audience — such as when he was asked how he would deal with extreme heat’s deadly impact on vulnerable populations. He said he was aware that soaring temperatures could make the city he called home uninhabitable. “The most important thing is to arrest the rate of warming on this planet — and that is my number one priority,” he said.

But his empathy for natural disaster victims went beyond the Lone Star State. When asked how he would help in situations like Hurricane Maria, where Puerto Ricans failed to receive timely and fair assistance, O’Rourke said he would fully fund disaster response agencies — not just after a disaster, but before. (O’Rourke also said Puerto Rico should have autonomy in determining its own future, whether it be through independence, statehood, or votes in Congress.)

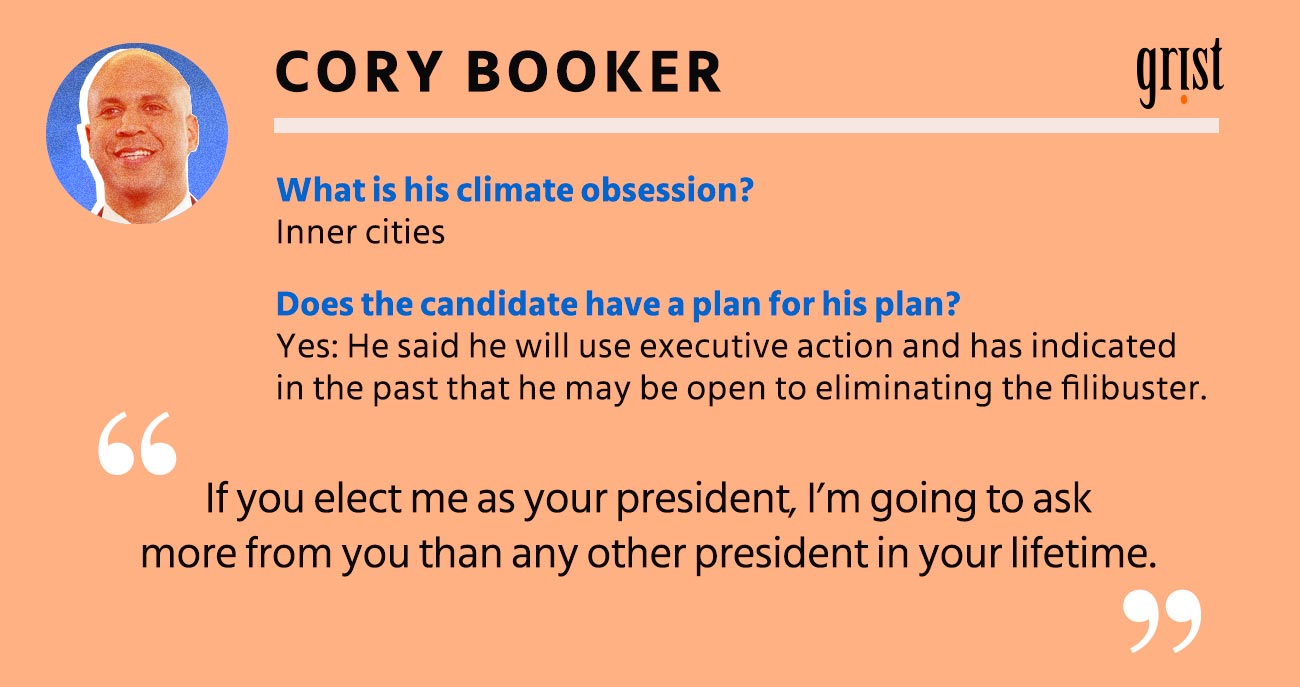

Cory Booker

Cory Booker is the former mayor of Newark, New Jersey — a city that is still grappling with the fallout from Superstorm Sandy and, more recently, a lead crisis with many similarities to the one in Flint, Michigan. He has long put environmental justice at the center of his climate platform, and a day before the town hall, he released a $3 trillion climate plan containing a prominent justice component.

“Every time there’s a natural disaster, you have to work through D.C. politics just to get the resources a family needs,” he said. “Enough of that.” He also challenged the idea that we’re just beginning to see the effects of climate change now — such as recent natural disasters, like Sandy. It’s been happening for a long time, he said.

He was one of a number of candidates to speak with relative ease about the role farmers can play in mitigating the crisis — cover crops, insurance programs, and pesticides were all on his menu. He said he would end subsidies for certain corporate farming practices that contribute to pollution and climate change. And when it comes to food, the only vegan in the primary was quick to point out that he’s not into policing anyone’s diet, but he is into finding solutions to inner-city food deserts.

As Grist has noted in the past, the New Jersey senator is a fan of nuclear energy. And he didn’t shy away from his embrace of nuclear, a position for which some climate activists have given him grief. “Nuclear is now 50 percent of our non-carbon-causing energy,” he said. “People who think we can get there without nuclear being part of the blend are not looking at the facts.”