The golden-cheeked warbler, an endangered songbird native to Central Texas, always seems to be flitting around controversy. It proved to be a roadblock derailing the Texas Department of Transportation’s plans to build a toll road in 2016. Prominent politicians in Texas say protections for the bird infringe on property rights. And in the last few years, the diminutive bird has survived multiple attempts to remove it from the federal endangered species list.

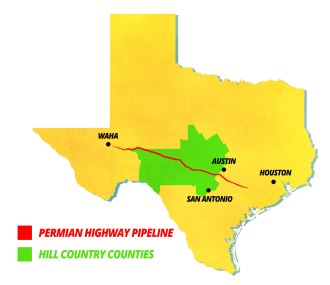

Now the warbler is at the center of a fight between Kinder Morgan and landowners in the Hill Country who want to block the company’s proposed pipeline through the 25-county region. Last fall, Kinder Morgan unveiled plans to build the Permian Highway Pipeline, a 430-mile conduit capable of transporting 2.1 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day from the Permian Basin in West Texas to the Gulf Coast. The pipeline route would cut right through some of the most pristine parts of the state, including vast swaths of oak-juniper woodlands, the warbler’s preferred habitat. It would also run over the Edwards Aquifer, a source of drinking water for more than two million people in Texas.

A group of Hill Country landowners, the Travis Audubon Society, and Hays County, part of the Austin metro area, recently notified Kinder Morgan that it plans to sue the company if it applies for federal permits to build the pipeline without an adequate plan to protect the warbler and other endangered species in the area.

“They want to do the bare minimum, so long as it’s cheap and fast,” said David Smith, an attorney representing the group. “This is all about trying to get their project built faster than their competitors’ projects. But none of their competitors are insisting on going through a very environmentally sensitive part of the state.”

The battle over the Permian Highway Pipeline comes amid a fracking boom in the Permian Basin, which is expected to provide a third of the country’s crude oil this year. It recently eclipsed production from Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar field, the world’s biggest oil field.

But without enough pipeline capacity to move the oil and gas to refineries and export facilities on the Gulf Coast, companies have resorted to burning off — “flaring” — an unprecedented amount of natural gas, which is primarily made up of methane, and worsening air quality in the region. Kinder Morgan claims its pipeline can relieve this bottleneck and provide “a much-needed outlet” for natural gas in the Permian, which it sees as an environmental benefit of constructing the pipeline.

For Lon Shell, a Hays County commissioner, reducing flaring in West Texas shouldn’t come at the cost to property owners and the environment. The pipeline could tamp down one problem, flaring, only to endanger drinking water and habitat somewhere else. “I understand that there’s production in parts of Texas that’s being wasted,” said Shell. “We can have a better process that still accommodates the needs of that industry, but also takes into account the concerns of our property owners.”

For Lon Shell, a Hays County commissioner, reducing flaring in West Texas shouldn’t come at the cost to property owners and the environment. The pipeline could tamp down one problem, flaring, only to endanger drinking water and habitat somewhere else. “I understand that there’s production in parts of Texas that’s being wasted,” said Shell. “We can have a better process that still accommodates the needs of that industry, but also takes into account the concerns of our property owners.”

The dispute over the warbler is just the most recent skirmish between Kinder Morgan and opponents of the pipeline. In April, a different coalition of landowners, Hays County, and the local city of Kyle, first sued Kinder Morgan and the Texas Railroad Commission, the state agency that regulates pipelines. The lawsuit claimed the state agency had “abdicated” its responsibility to the public and that Texas’s eminent domain process is unconstitutional, because it gives corporations the authority to condemn land and build through private property without giving the public a chance to voice concerns.

Although the Travis County district judge said she was “concerned” that a private entity could use eminent domain “without public notice … [and] driven primarily by their financial interests,” she ultimately ruled in favor of the Kinder Morgan, stating that the court could “not dictate the policy of the state.” The landowners are appealing.

The pipeline’s opponents are now planning to challenge the company and federal agencies — including the Army Corps of Engineers and the Department of Interior — over the federal permitting process. At issue is the type of permit that Kinder Morgan would secure from the Army Corps and whether the process would adequately consider the effects of the pipeline on the warbler and other endangered species.

Kinder Morgan appears to be applying for a series of permits for sections of the pipeline that cross streams and rivers under federal jurisdiction, according to a notice of intent to sue sent by the landowner coalition last month and the company’s public statements. Smith, the attorney for the landowner coalition, claims those permits will cover at most five percent of the pipeline. If the Army Corps approves them, Smith said, Kinder Morgan would be required to assess the environmental risks of just those sections of the pipeline that cut across streams. The threats posed by the remainder of the pipeline — at least 95 percent — to the warbler and other endangered species would go unaddressed, he said.

“This is a thinly-veiled attempt to avoid obtaining the necessary federal permits,” the notice reads.

Katherine Hill, a spokesperson for Kinder Morgan, said that the company is “complying with all applicable laws related to endangered species along the pipeline route.” Hill declined to respond to specific questions about the company’s plans to obtain permits from the Army Corps and its efforts to protect the warbler’s habitat.

According to the letter sent by the landowner coalition, Kinder Morgan has proposed mitigating the effects of constructing through warbler habitat by paying for conservation efforts in neighboring Burnet County. But Shell, the Hays County commissioner, bristled at the idea that the company would damage habitat in one county and pay for mitigation in another.

“Kinder Morgan has never approached the county about mitigating any of the impacts that they’re having on habitat, which is a concern to us because we’ve invested a great deal of resources into the preservation of that habitat for many years now,” Shell said.

Jim Bradbury, a prominent attorney who has represented ranchers and farmers, has been advocating for bills that would increase public participation in eminent domain proceedings and protect landowners from low-ball offers for their property. But those bills stalled in the state House in May, after one powerful lawmaker watered down the bills. If the Texas legislature had passed those bills, Bradbury believes the battle playing out over the Permian Highway Pipeline wouldn’t be as pitched.

Some cities have stepped in to try to protect their residents. The city of Kyle adopted an ordinance last month requiring pipelines to be buried 13 feet deep in some areas. Kinder Morgan is challenging the ordinance in federal court, arguing that federal and state pipeline laws take precedent.

While many opponents would like to see Kinder Morgan drop plans to build the Permian Highway Pipeline altogether, others just want the company to pick another route. Cities in the Hill Country are among the fastest growing in the United States, and with rapid development along the I-35 corridor that runs from Austin to San Antonio, opponents say the pipeline should be routed through a less dense part of the state.

Bradbury said it’s “unusual” for a pipeline company to try to build through a place like the Hill Country, home to lush green pastures, clear springs, a key source of the region’s drinking water, and the much-loved golden-cheeked warbler.

“How Kinder Morgan never thought this wouldn’t be an absolute nightmare, dealing with a lot of older people, retirees, really determined folks and a pristine area of the Hill Country, I don’t know.” said Bradbury. “They really got themselves in a mess.”