Dear Umbra,

I’m planning on kayaking the Inside Passage next summer and am having a hard time deciding what kind of boat to get. Are there any environmental reasons to choose a kayak material? Mostly I’m torn between plastic, which is cheaper and more durable, vs. fiberglass, which is lighter and faster, or Kevlar, which is even more expensive and lighter. I’ve decided against wood because I don’t think it is durable enough. What about a new material called Airalite?

Amanda Babson

Seattle, Wash.

P.S. Thanks to your advice, I’ll be avoiding PVC dry bags.

Dearest Amanda,

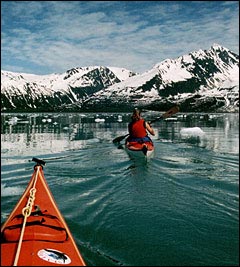

Your trip sounds fabulous. Hooray for human-powered explorations.

Whatever floats your boat.

Photo: Tom Twigg

It’s exceedingly wise, if occasionally taxing, to assess the environmental impacts of our chosen modes of recreation. I’m delighted to hear you’re thinking about it. You’ve made a wise choice on the dry bags, and now it’s time to consider the boat. A good environmental assessment of a given material, as I see it, includes the three phases of its life: manufacture, use, and afterlife.

In the manufacturing phase, all of the materials you mentioned have some negatives. (I will leave wood aside, since you have, but it certainly has its ardent supporters.) Plastic and Kevlar (as well as Airalite [PDF]) are petroleum-derived, and fiberglass manufacture [PDF] relies on the use of toxic resins and gel coats that contain the chemical styrene. In addition, Kevlar manufacture requires concentrated sulfuric acid, which makes working conditions intense — and is also one of the reasons it’s so dang expensive compared to the other materials.

At this stage there are no clear winners in the materials race, but let’s move on to the fun part of a kayak’s life: its use.

Good measures of eco-value in the use category are strength and durability, especially since the Inside Passage is notoriously rocky and surfy, with the added danger of encountering sharp mussels and barnacles. Plastic and Kevlar — as well as Airalite, it seems — are strong materials that can stand up to the abuses of the Alaskan shoreline and are likely to last a good long while. Fiberglass, however, is less strong. In the words of Grist’s resident kayak expert, who worked as a guide in Alaska for 10 years, “When faced with landing on a surfy, rocky beach, concern for your fiberglass hull can lead you to linger in the surf zone too long, which increases the likelihood of damage to you.” Ouch. (Though fiberglass and other composites can usually be patched if you do get a hole in the hull, that may not be a risk you want to take on a wilderness trip.)

When we consider a kayak’s afterlife, we seem to find a clear winner. While fiberglass, fiberglass-like composites, Airalite, and Kevlar are essentially not recyclable, plastic kayaks can be recycled. Word around the campfire is that some manufacturers of plastic kayaks, like Perception (which is actually also the maker of Airalite), will sometimes take the product back and reincarnate it.

Another consideration, of course, is cost. According to my in-house expert, “You can outfit two people in good plastic boats (with some extra gear thrown in) for what one Kevlar boat would cost.” Airalite apparently isn’t a lot more expensive than plastic, but given the recyclability factor, plastic might be the overall winner.

Of course, you’ll want to try out different models before buying, to find a kayak that is comfortable for you and your wallet, and designed to haul enough gear for a multi-day trip. You don’t want to end up wishing you’d bought something lighter and faster — regret has a way of sinking in rather efficiently over several days of unnecessary exertion.

Whatever you choose, know that powering yourself in the water (and out of it) makes for a relatively innocuous pastime, environmentally speaking. So don’t let the materials question keep you up too late.

Paddly,

Umbra