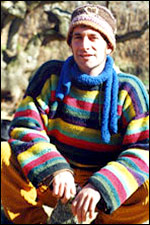

Sandor Katz.

Like a well-made batch of kefir, the ancient cultured milk drink, Sandor Katz has an effervescent quality. Spend time with him or read his classic Wild Fermentation, and you’ll see your food in a new light. Bread, cheese, cured meats, chocolate, beer, wine, vinegar — all are products of fermentation, he points out: “Virtually all of the compelling, strong flavors that people are passionate about — they might passionately hate them, or they might passionately love them — it’s fermentation that creates those flavors.”

Fermentation is the process of preserving food and transforming its flavor by subjecting it to beneficial bacteria, or microflora. For Katz, fermentation is an essential culinary technique, a health regimen, and a political act. “We humans are in a symbiotic relationship with single-cell organisms,” he writes in Wild Fermentation. “Microflora … digest food into nutrients our bodies can absorb, protect us from potentially dangerous organisms, and teach our immune systems to function.” In a country almost clinically obsessed with sterilization — with waging war on the trillions of dread germs that permeate air, land, water, and our bodies — Katz reminds us of the forgotten benefits of living in harmony with our microbial relatives.

He also urges us to challenge our roles as unquestioning consumers of the food industry’s dubious wares. His message: with everyday ingredients, you, too, can be a producer, not just a consumer — of some of the most vibrantly flavorful, health-giving foods you’ve ever had. His critique of the food industry, and celebration of the myriad alternatives bubbling forth to challenge it all over the country, can be found in his new book The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved: Inside America’s Underground Food Movements.

Katz himself is a walking advertisement for the health benefits of foods that are alive with organisms. Since the 1980s, he has lived with HIV. Yet he bristles with energy, touring the nation to deliver fermentation workshops when he’s not herding the goats at Short Mountain Sanctuary, the “queer intentional community deep in the wooded hills of Tennessee” where he lives.

Recently, over sips of delicate, profoundly alive-tasting kefir made from raw milk from those goats, we talked about fermentation, food politics, and how the two relate.

You suggest, through your work, that we shouldn’t mindlessly consume processed food, but instead get involved with production — why?

We’re living in this time where people have largely lost our direct connections to the natural world and it’s all mediated for us by a few people in the middle. And as with any kind of an organism, food connects humans to their environments and the natural world. So if you’re gathering food you have to know about the local plants. If you’re hunting, you’re interacting with animals. When you’re just going to the supermarket, you lose that interaction.

Katz teaches the joys of fermentation.

Identifying solely as consumers is just a limiting, infantilizing role. Sure, we can be consumers, but we also can be producers and everybody can be both of those things. And fermenting your own food … you’re not only producing food, but you’re interacting with invisible natural forces.

I meet so many people who have a memory of a grandparent who had some sort of an annual fermentation ritual, whether it was making sauerkraut, making wine, making pickles. Really until 50 years ago, 75 years ago, it was really, really common at the household level for people to ferment some of their foods.

In a small but profound way, getting involved with fermenting food in your home is a way to embrace the bacterial allies that are all around us. And rather than getting caught up in the foolish, indiscriminate war on bacteria, we can embrace the bacteria around us and turn them into our physiological allies.

Why shouldn’t we fear those invisible creatures?

Bacteria can be your friends.

Well, on every head of cabbage, on every vegetable, for that matter in every breath that you ever take without going to the grocery store, there are untold numbers of different microorganisms, including not only bacteria, but fungi, and who knows what else?

The art of fermentation is about creating the conditions that support the growth and proliferation of certain types of organisms rather than certain other types of organisms. So for instance, if you took a half of a head of cabbage and went away on vacation for three weeks and came home, obviously it would not turn itself into delicious, sour, crunchy sauerkraut. If you go away for a really long time, molds can start to reduce your vegetables to a puddle of slime. The simple key to getting the acid-producing bacteria to grow [instead] is to get the vegetables submerged under liquid, typically a salty liquid. It’s just a matter of learning simple secrets for encouraging healthy types rather than unhealthy types to grow.

Farmers do something very similar: suppress some plants so that desired ones can flourish. What you’re describing is a kind of micro-agriculture.

Fermentation techniques appear to have coevolved along with agricultural techniques — let’s picture the domestication of animals for milk. The various places that happened, they didn’t have refrigerators to put their milk into and keep it fresh. So it only made sense to ferment the milk into cultured products, like yogurt and kefir, to enable people to enjoy the milk, be nourished by the milk, for longer than the day or so that milk will stay fresh.

When you look at plant agriculture, archaeologists continue to debate whether people in the Fertile Crescent settled down into patterns of agriculture for bread or for beer. And both of those are products of fermentation, so the history of agriculture has everything to do with the history of fermentation.

Just as a footnote I think that that debate is kind of moot, because the earliest written recipes from the Sumerians for beer call for an undercooked loaf of bread with the yeast of the center still raw as the starter for the beer, and they call for skimming the foam off of the top of the beer as the starter for the bread. So those two wonderful fermented products of grain agriculture have always had an intertwined history.

Interestingly, the word we use for bacteria that we use in the fermentation process is culture — the same word that we use to describe literature, language, music, science, the totality of human knowledge. It’s not an accident that we use the same word for both of those things. And most religions have ritual iconography organized around fermentation and fermented products … In the Jewish tradition that I live in, we always have reverential toasts to the creator of the fruit of the vine, and drink wine. Really, anthropology is full of examples of rituals structured around fermentation.

How did you go from writing about fermentation to writing about food politics? How do you relate the two?

Well, The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved was inspired by people I met as I was traveling around talking about fermentation, farmers who were trying to re-create markets for local food and figure out value-added products to help make their farms viable. Then dumpster divers, who often will find a great abundance of some random vegetable or fruit, have found that fermentation is a really great way of turning abundance like that into a resource that people can enjoy over time.

So at one level the book is the story of people who I met … traveling around teaching and talking about fermentation. And then at another level, at the end of the book Wild Fermentation, I talk about this other connotation of the word “fermentation,” which comes from the Latin word fervere, which means “to boil.” That’s because the visible action of fermenting liquids is the same bubbliness you see in boiling liquids. But there’s this other connotation of the word “fermentation” that’s about the social ferment, the intellectual ferment, the spiritual ferment, and it has to do with people who are passionate and excited about something and so they get like a bubbly quality to them where they want to talk about it, they want to do something about it, and I think that that’s the point of departure for The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved. People who want to create better food alternatives for themselves and the people in the communities around them. The book is about food activism and people trying to create better choices.

I like the way you address the fallacy that in order to “feed the world,” we have to hand agriculture over to Monsanto and a few other giant companies.

We’re all constantly subjected to this propaganda that without intensification, without genetic modification, without pesticides, without chemical fertilizers, without tractors, there would be no way of feeding the growing numbers of people in the country, in the world, and that the only thing standing between us and mass starvation is the intensifying technology of agriculture.

But that’s all about really maximizing production per unit of labor. I mean right now less than 2 percent of the American population is engaged in direct agricultural production and this is held up as a miracle, freeing us up to do all the other important things we do like be real-estate brokers or stock brokers or produce widgets or other things like that … anything but getting our fingers dirty in the soil.

But it turns out that using more labor-intensive methods, an acre of land can definitely produce more if it’s not monocultured. You know, if you have different crops growing at different levels: things growing underground, things growing on the ground, things growing above the ground, things growing at different periods of the season. If you’re cultivating by hand you don’t need lots of space between the rows for tractors to go.

If the imperative were maximizing the production per unit of land, which really is the fixed variable, then I think more labor-intensive methods actually could be much more successful at feeding a growing population. Land is limited, but there’s no shortage of people.

That would mean more farmers and fewer stockbrokers and telemarketers. As someone who’s crisscrossed the country talking to people about food, what do you think the prospects are for such a switch?

There are so many exciting, inspiring, hopeful, small projects happening. The thing is that they’re small, especially in comparison to the dominant food system where the trend continues to be toward market concentration at every level.

I’m not blindly optimistic — looking at the big picture can lead to despair and pessimism. For me, though, it just feels like a better choice to put my energy, and for anyone to put their energy, into projects that create hope. And I think that there’s nothing more hopeful that somebody can do than get involved in local food production.

I’m very inspired by Wendell Berry, who talks about how thinking [small] solves half the problem. All the problems of globalized commodity agriculture and foods traveling thousands of miles from farm to the plate, those are the result of people sort of thinking bigger and bigger, and I think the solutions come from people thinking smaller. And that’s why community gardens and community-supported agriculture and community kitchens and things like that are all part of the solution, because they enable people to focus on their needs and their community’s needs and satisfying those needs. I really think we need to just focus on small things within our realm that we can actually do.