Some half a million acres of the most productive agricultural region on the planet — California’s San Joaquin Valley — will have to fall fallow, a new report says. There just isn’t enough water.

Farmers have been using so much water that wells have run dry and the ground has sunk as much as 28 feet in places. So California passed a law back in 2014 to stop its overdraft of groundwater and gave itself 20 years to figure out how to make it work. According to a report just out from the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California, it will require giving up a chunk of farmland more than twice the size of San Diego.

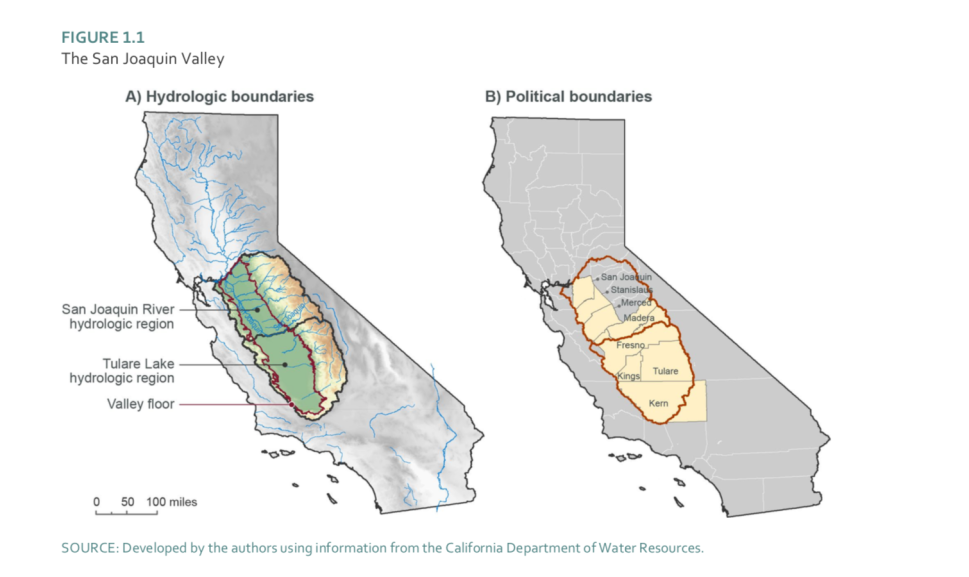

The San Joaquin Valley is a massive, flat-bottomed bowl that curves from east of San Francisco to Bakersfield. It’s dry, a saltbush desert in some places. But by tapping snowmelt from the Sierra Nevadas and groundwater, farmers are able to control soil moisture with precision, turning it into the state’s largest agricultural region and an important source of the country’s food. Anytime you have grapes, oranges, lemons, or anything involving tomato sauce, you’re probably swallowing groundwater pumped out of the San Joaquin’s collapsing aquifers.

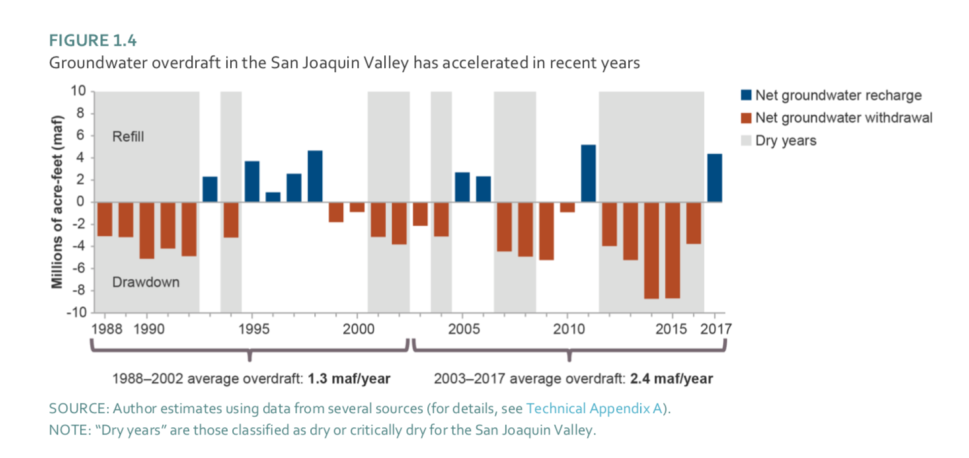

California’s climate has always swung between wet and dry years, and climate change is projected to make that oscillation more extreme. The state’s historic drought, followed by floods, looks a lot like those predictions coming to life. In recent years, farmers have been dealing with drier weather by sucking more and more water from the ground.

The Public Policy Institute’s report considers all options: water recycling, growing different crops, piping in more water, and building new reservoirs. But many of these options make water more expensive than farmers can realistically pay; hence, the recommendation for letting some farmland go. If California does everything right, the report suggests, the San Joaquin Valley would need to idle one out of every ten irrigated acres to achieve sustainable water use.

The report doesn’t examine what this would mean for food prices — except for a passing mention that it could raise prices for almonds and pistachios.

Those unirrigated acres could soon be put to other purposes. Some of could be filled with solar panels, and some could be returned to native ecosystems — deserts and seasonal floodplains. Farming has transformed the valley’s ecology over the last 150 years, and the state might benefit from restoring some of that landscape.

Finally, some idled farmland will likely turn into cities to house some of the state’s nearly 40 million people (and growing). But that would only work, the authors caution, if these new residential areas sip water from existing urban supplies.