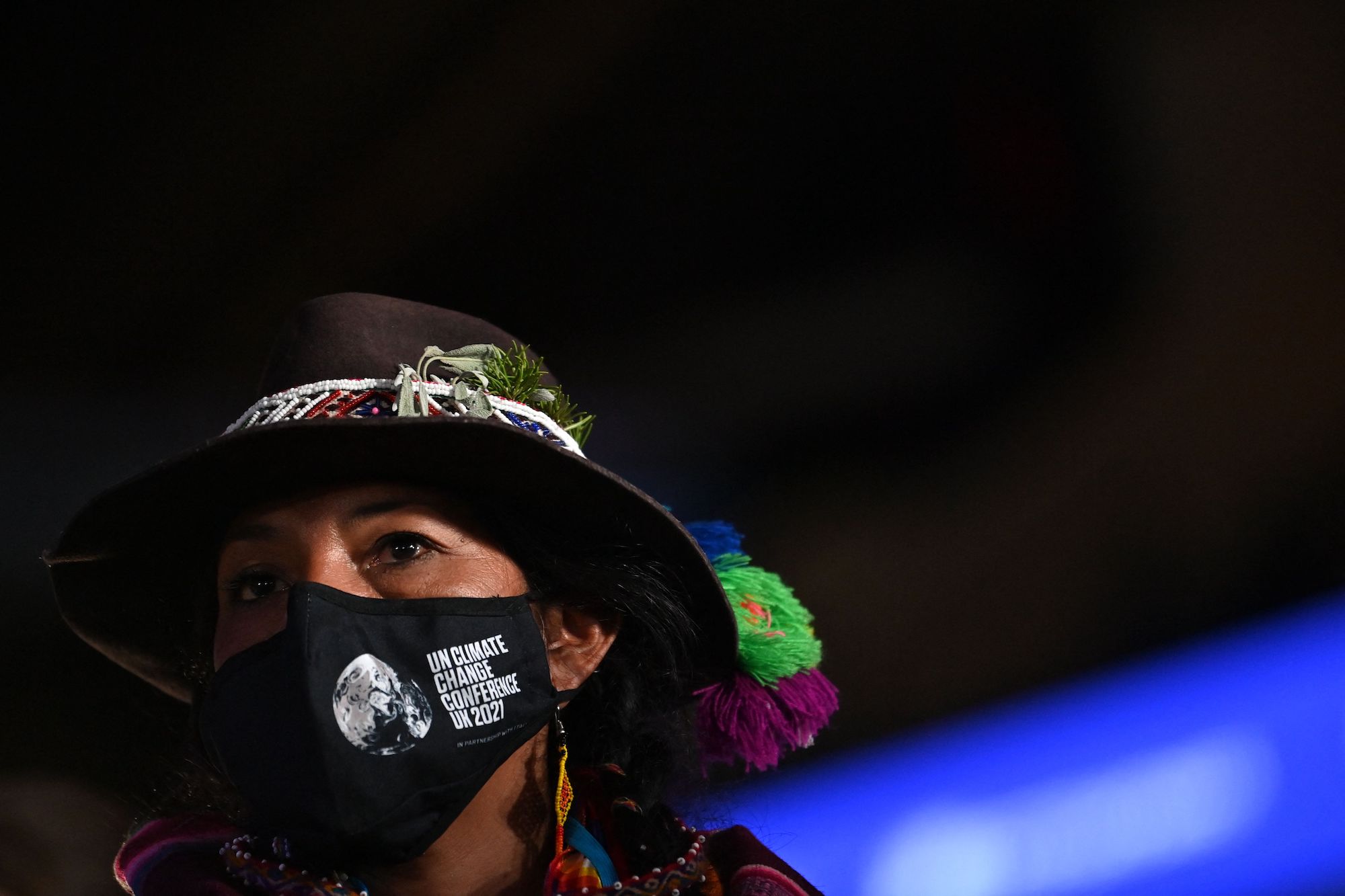

After two intense weeks in Glasgow, Scotland, Indigenous leaders attending the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference are finally returning home. As the dust settles, many of them have begun to process the agreements reached by the nearly 200 nations. Indigenous communities went to COP with a clear set of demands. But they leave with a few symbolically significant, yet vague commitments.

“The final text left me sad, angry, empowered, and scared,” Eriel Deranger, executive director of Indigenous Climate Action, said in a press release.

That mixed bag of emotions seems to be a common denominator for Indigenous leaders attending the conference. “We always arrive with big expectations and ambitions,” Gustavo Sánchez, president of the Red Mexicana de Organizaciones Campesinas Forestales, an organization that represents local and Indigenous communities from Mexico, told Grist. “So [the meeting] always ends up owing us.”

Indigenous people arrived in Glasgow as a united front, demanding the inclusion of Indigenous and sovereignty rights in every single climate action decision being made at the conference. They wanted to ensure any climate agreements affecting them or their lands would only take place after a process of prior and informed consent, as well as a clear path to present grievances in case their rights were violated by a project. They wanted to secure mechanisms so that funding would flow directly to them, and a recognition of both the material and cultural losses that climate change is already driving. For the first time in COP history, they found themselves in direct and constant contact with the inner decision-making circle. But COVID-related travel restrictions and funding gaps kept many key leaders at home. And while they managed to get explicit mentions in the final text and articles of their rights, the value of their traditional knowledge, and the need to include Indigenous groups in climate solutions, there’s uncertainty on how nations will bring those words into reality.

“There’s not a clear guide on how our participation will become more active and effective,” said Eileen Mairena Cunningham, who represented the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change, or IIPFCC, at COP. The agreements reached in the past two weeks acknowledge the need to respect Indigenous rights, she said, but they don’t lay out a clear path on how governments and companies need to act to ensure no rights are violated in the name of fighting climate change.

Months before the meeting at Glasgow, Indigenous peoples felt hopeful. COP26 President Alok Sharma made efforts to include them in high-level discussion panels, such as the World Leaders Summit, said Jing Corpuz, a member of the Kankana-ey Igorot people in the Philippines and the global policy and advocacy lead for the nonprofit Nia Tero. Those who managed to attend COP26, Corpuz noted, had an unprecedented presence in “the blue zone,” or the zone where official conversations and high-level panels are held. This gave them the chance to speak directly to decision makers.

“Twenty years ago, we were relegated to the general public areas,” said Sánchez, who went to Glasgow representing Mexican Indigenous and local communities. “This has been the COP where we have had more high-level meetings and where we have found more opportunities to talk about our perspectives.”

Most of the assisting delegates, however, were from the Arctic, the Americas, and the Caribbean. Indigenous peoples from Africa, Asia, Russia, and the Pacific were less well-represented, Corpuz said. Visa approvals stalled and traveling restrictions due to the pandemic made an already complicated process even more kafkaesque. For example, all visa applications from African delegates were processed through one office in South Africa. When the UK reopened its borders to flights from the Philippines, where Corpuz lives, just a week before the meeting, she had to personally go to her country’s visa application center for two entire days so they could review the application she had sent months in advance. These details made representation unevenly distributed, she said.

That unequal representation likely impacted the agreements reached at the summit.

Some 141 countries committed in Glasgow to end deforestation by 2030 and restore degraded woodlands. But pledges to protect oceans — huge carbon sinks and home to many Indigenous communities, particularly from small Island nations in the Pacific — were once again sidelined in the negotiations and financing conversations.

The disappointing outcomes of the loss and damages section, which deals with resources and funds to support countries that are already feeling the impacts of climate change, like the islands from the Pacific, also showcase that power imbalance, Corpuz said.

Those shortfalls were frustrating, but leaders did point to several significant victories for Indigenous peoples from forested areas. The deforestation pledge included explicit recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights and the need to increase the support they receive. Days later, countries and companies promised $1.7 billion to support Indigenous and local communities’ efforts to protect their territories. It’s the largest sum ever announced for these communities — a victory achieved after five years of coordinated efforts by a coalition of Indigenous communities from Central America, the Amazon, Indonesia, and the Congo Basin, explained Sánchez, who is part of that coalition.

Perhaps one of the biggest wins was the last-minute inclusion of explicit recognition of Indigenous rights in the text of Article 6, the article of the Paris Agreement that regulates carbon offsets markets. For years, Indigenous peoples had been denouncing that these projects could end up displacing communities or altering their ways of living without their consent. The mention was celebrated by Indigenous leaders — although not praised.

“There is no legally binding responsibility to adhere to this language,” said Jade Begay, climate justice campaign director at NDN Collective, which represents Indigenous communities in North America. The text only requires “consultation in accordance with domestic arrangements” for Indigenous peoples when designing activities in their lands — meaning that in countries where the rights of Indigenous peoples are not fully recognized, the projects can go on, even in violation of international human rights standards. “That’s really concerning because these loopholes [can] continue ongoing land grabs and violations to human and indigenous rights through the carbon market,” Bagey said.

Looking forward, Indigenous peoples want to have direct access to the financing promised to support them, explained Sánchez. The Alianza Mesoamericana de Pueblos y Bosques, from Central America, just launched the first Indigenous-driven financing mechanism hoping to channel funds directly to their communities. However, communities that have not created a similar strategy need internationally-agreed tools to ensure direct delivery of funds.

A seat on the negotiation table remains the ultimate goal. “None of the official negotiating nations are tribal nations,” Bagey said. “And I think that’s a failure of the UN recognizing Indigenous peoples’ rights.”

Yet she remains hopeful. “When I see people say things like ‘COP totally failed,’ I feel a little cautious. We can’t negate the small wins. Because we need to keep cheering each other on.”