This story was originally published by Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

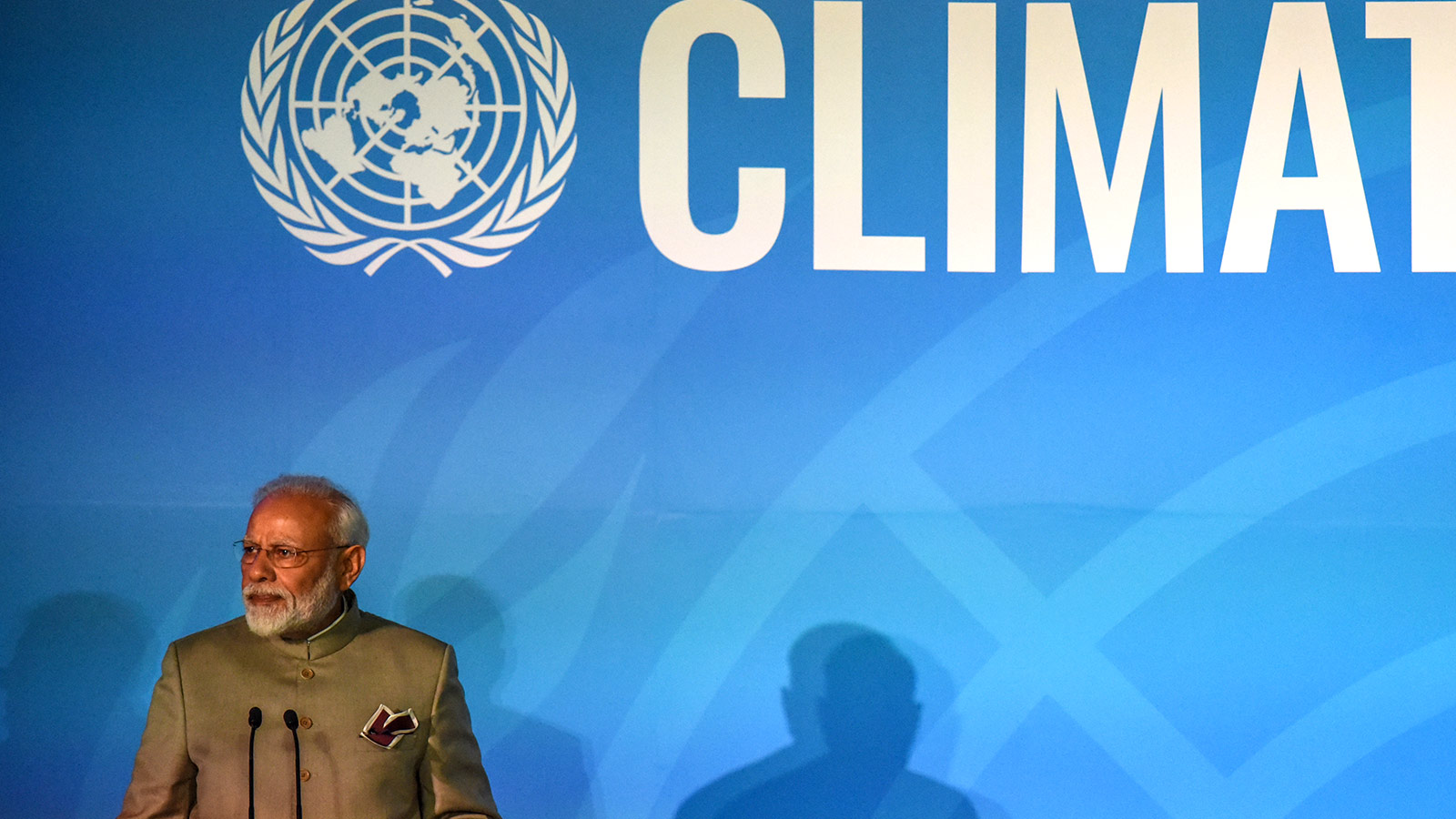

If you watched Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s top-billed speech at the United Nations Climate Action Summit on September 23, you might be inclined to say the South Asian leader is very serious about climate change. In his brief remarks, Modi touted his “Champion of the Earth” designation, emphasized his renewable energy and water conservation goals, promoted India’s global solar panel network, praised the newly announced Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure, and boasted about India’s forthcoming ban on six different types of single-use and disposable plastics, which is set to be instated nationwide this week. Two days after, Modi, joined by the leaders of six other nations, helped inaugurate the Gandhi Solar Park and Gandhi Peace Garden at the U.N. headquarters, installing India-manufactured solar panels on the roof.

Modi knew that all eyes would be on him. As the need for sweeping climate action grows more urgent, the world has been desperately following what India will do next. The country is often perceived as being at the forefront of global climate action. As the world’s largest democracy (a dubious distinction of late), seventh-largest economy, second-largest nation by population, and third-largest carbon emitter, India’s actions are of utmost importance. One only need remember the COP21 talks that gave birth to the Paris Agreement, where India was seen as a key signatory and Modi was viewed as the champion of the participating developing nations, particularly given his role as one of Barack Obama’s toughest challengers when it came to setting global temperature and time frame standards.

But anyone who’s looked closely at the past half-decade of energy policy in India should realize that Modi’s grandiose statements — and India’s place as a global climate leader — warrant some skepticism. After all, this is the man who was elected to his first term, in 2014, as a free enterprise–friendly demagogue ready to prioritize economic growth first and foremost. In his first year as prime minister, he didn’t even bother showing up at the U.N. climate summit. Instead, he suggested that it might not be the climate that’s changing, but humans’ ability to adjust to nature. In a troll-y move his good friend Donald Trump would be proud of, Modi bestowed upon India’s environmental ministry its new title as the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change — and then slashed its budget by a quarter. He likewise cut the budget for the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. Funds were blocked to environmental groups, initiatives, and NGOs, and Modi pursed an aggressive privatization and deregulatory policy that loosened restrictions on mining, coal, oil, and gas companies. Pollution standards were relaxed, and development projects were given free rein to operate in forests and other natural areas, contributing to deforestation.

These measures were all enacted pre-Paris, but even following the landmark agreement, the situation hasn’t gotten much better (and it’s unclear what future climate agreements will be to India’s satisfaction, given that it refused to be a signatory to 2018’s COP24 Silesia Declaration on just transitions). Instead of meeting the promise of supplying every home in India with electricity from renewable sources, the government keeps ramping up coal production. Restrictions on deforestation and atomic mining have continued to be relaxed. It’s true that the government imposed controls on thermal coal production — but then it excused hundreds of plants from following them.

Nuclear power is currently the fifth-largest source of electricity in India, but isn’t likely to grow anytime soon. There are only a few low-capacity plants currently in operation: Some states barred the construction of new plants following the Fukushima disaster. (India has had no problem keeping its nuclear arms arsenal well-stocked, though.)

Even as funding for the climate change ministry has increased, it’s remained unclear which projects are getting new infusions of cash. Indian states vary wildly in their individual agendas, with some states refusing to adopt national climate standards and others failing to allocate sufficient funds for action in their budgets. The government’s true priorities during this year’s election season are perhaps best understood by reading the 45-page-long 2019 manifesto of Modi’s party, which contains only 10 vague bullet points related to the environment.

All these actions might seem to undermine Modi’s lofty rhetoric on climate. But if you ask the prime minister and his deputies, they’ll just say they’ve deemed it a necessary part of kickstarting India’s economy, welcoming foreign investment, and increasing access to essential resources for the citizenry — all reforms they also touted on their rise to power and intend to fulfill. It’s true that fossil fuels are currently the fastest and cheapest way to bring electric power to millions of Indians who lack access (still a problem, despite Modi’s talking point that all Indian villages are now connected to the grid). But prioritizing green energy developments above all else could have helped connect people, while also making these cleaner sources more competitive with fossil fuels. It goes to show how much of an incoherent mess India’s domestic climate policy is.

There are accomplishments, like heavy investment in wind power, mass distribution of energy-efficient LED lights, and public transit development in major cities like Delhi. But these are then offset by continued dependence on dubious energy alternatives like biofuels and “clean coal,” failed busing plans, and steeply falling transit ridership rates (citizens are increasingly buying diesel-chugging SUVs and other gas-guzzling automobiles). Plus, India belches carbon at a significantly lower rate than China and the U.S., but it still outpaces other developing nations by bounds.

India’s justification for its mixed progress thus far is found in the talking point Modi repeated in the lead up to this year’s U.N. summit: that the primary responsibility for climate action shouldn’t rest on countries like India, but on the U.S. and other Western nations that should be doing much, much more to tamp down their own emissions and aid developing nations. India certainly contributed much less to causing this problem and, alongside its history of colonial plunder, shares much less of the culpability. But the current situation underscores the problem with holding out on taking drastic climate action because other countries ought to be doing more — climate disaster is coming to India no matter what.

In fact, environmental disaster is already part and parcel of Indian life. This year alone, the city of Chennai underwent a Day Zero, where taps were shut off because reservoirs were almost out of water. Plenty of other Indian cities are experiencing severe water shortages, which portend environmental-linked violence. (Part of India’s historic conflict with Pakistan is spurred by disputes over the water supplied by the Indus delta. As Modi demonstrated earlier this year, he’s very willing to be aggressive with Pakistan.) Heat waves have been more severe than ever this year, with summer temperatures exceeding 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit).

Dozens have died of heatstroke just this summer, and the heat waves have particularly tragic effects for rural farmers, with some research suggesting extreme heat is positively correlated with higher suicide rates. The state of Kerala was pummeled by monsoon flooding, killing hundreds. Air pollution reached emergency levels of toxicity in cities like Delhi. Climate change is not a distant reckoning for India — countless people are already suffering thanks to insufficient reforms.

There are other, darker signs of what’s to come. India’s harsh treatment of Rohingya asylum-seekers and Bangladeshi climate refugees, its crackdown on Kashmir, and its current disenfranchisement of its own citizenry and push for detention camps all foreshadow how the government will handle inevitable mass displacements that will occur throughout South Asia in the future. Modi himself has started to advocate for population control and “small families” in speeches: Bills introduced in Parliament would forbid families with more than two children from applying for government jobs, among other penalties.

But maybe, just maybe, this year could represent a turning point. Difficult as it is to extrapolate how far-reaching citizen climate activism is within India, grassroots movements are indeed gaining ground, fueled by citizens who understand that their fate, or at least their children’s, is linked to what they do right now. There are farming cooperatives in local villages and activist collectives in the Himalayas taking action in their communities. The climate action group Extinction Rebellion is making headway amongst Indian youth, and there was mass participation in last week’s Global Climate Strike. A young girl filed a lawsuit against the Indian government on behalf of children alive and unborn, taking it to task for insufficient climate action, in a similar move to the U.S.’s Juliana case. It’s a significant shift from just a few years ago, when the government was infamously afraid to take public action because about 39 percent of Indians said they had never even heard of climate change. In this year’s elections, though, environmental issues were high on the list of citizens’ concerns.

In other words, the people understand that action on climate is necessary — for the world and the future, yes, but also for them right now. And the Indian government might finally be treating the issue with even more seriousness and urgency than before: In July, Modi’s cabinet presented what the prime minister hailed as India’s first “green budget,” including increased investments in electric vehicles, as well as a dramatic increase in money to stem pollution and regrow forests. The world can only hope Modi’s promises last this time around.