Two Democratic primary debates down, at least six more to go (sigh). But compared to last month’s pair of candidate face-offs, during which there were only about seven minutes of climate discussion each night, the second debates were a virtual climate policy gabfest.

It’s not just that candidates spent more time discussing climate — about 12 minutes on each night. The second debates featured a much stronger dialogue about what Democratic candidates might do if they took up residence in the Oval Office — and talk stretched far beyond just name-dropping either the Paris Accord or the Green New Deal, the bold proposal that seems to have helped supercharge political dialogue on warming.

It’s no surprise that Washington Governor Jay Inslee spoke confidently about what he’d do to slow climate change. But did anyone expect Ohio Congressman Tim Ryan to talk about the promise of carbon farming? Or for Senator Kirsten Gillibrand to say we should challenge China for clean energy supremacy??

Though talk of climate solutions certainly didn’t receive the time nor the detail of, say, health care, the TV audience nonetheless saw potential political leaders debate and evaluate actual policy ideas in a way they had never been discussed on-air before. Here are some highlights:

Things got wonky

Naturally, when talk turned to climate on both nights, moderators and candidates were quick to mention the Green New Deal, a resolution that has driven a wedge between moderate and progressive candidates. But candidates also debuted climate-related terms typically reserved for use in deep-state environmental circles.

John Delaney championed direct air capture — a complex, expensive technique for carbon reduction that’s considered difficult to scale. “I’m going to create a market for something called direct air capture, which are machines that actually take carbon out of the atmosphere, because I don’t think we’ll get to net-zero [carbon emissions] by 2050 unless we have those things,” the former congressman said.

Ohio Representative Tim Ryan focused on soil sequestration, basically burying emissions in dirt via farming methods. It’s a component of regenerative agriculture, another term Ryan employed. “You cannot get there on climate unless we talk about agriculture,” he said. “We need to convert our industrial agriculture system over to a sustainable and regenerative agriculture system.”

Beto O’Rourke, the former Texas representative, seemed to agree with Ryan, offering up another component of regenerative agriculture. He suggested paying farmers for planting cover crops (like clover, for example) which turn unused fields into carbon sinks during off-seasons.

Not to be outdone, Bernie Sanders invoked the term just transition, a central component of the Green New Deal that ensures fossil fuel workers aren’t left behind in a shift to a green economy.

Green New Deal or no deal

Moderates were full-throated in their criticism of the Green New Deal on Tuesday night. Former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper said it would be a “disaster at the ballot box.” John Delaney called the plan unrealistic because it’s tied to “things that are completely unrelated to climate, like universal health care, guaranteed government jobs, and universal basic income.”

Those attacks left Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — cosponsors of the Green New Deal resolution introduced in Congress by Senator Ed Markey and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — to defend the proposal “We can create what the Green New Deal is about,” Sanders said. “It’s a bold idea.”

Warren took the opportunity to sketch out her version of what such a policy might look like: “I’ve proposed putting $2 trillion in so we do the research,” she said. “We then say anyone in the world can use it, so long as you build it right here in America. And the second thing we will do is we will then sell those products all around the world.”

When Gillibrand, another Green New Deal co-sponsor, was asked to explain how the proposal was realistic, she opted for a familiar patriotic analogy.

“When John F. Kennedy said, ‘I want to put a man on the moon in the next 10 years, not because it’s easy, but because it’s hard,’ he knew it was going to be a measure of our innovation, our success, our ability to galvanize worldwide competition,” she said, referencing a government effort often invoked when discussing climate action. “He wanted to have a space race with Russia. Why not have a green energy race with China?”

She went on to paint the Green New Deal as achievable, by comparison. “Why not rebuild our infrastructure?” she asked. “Why not actually invest in the green jobs? That’s what the Green New Deal is about.”

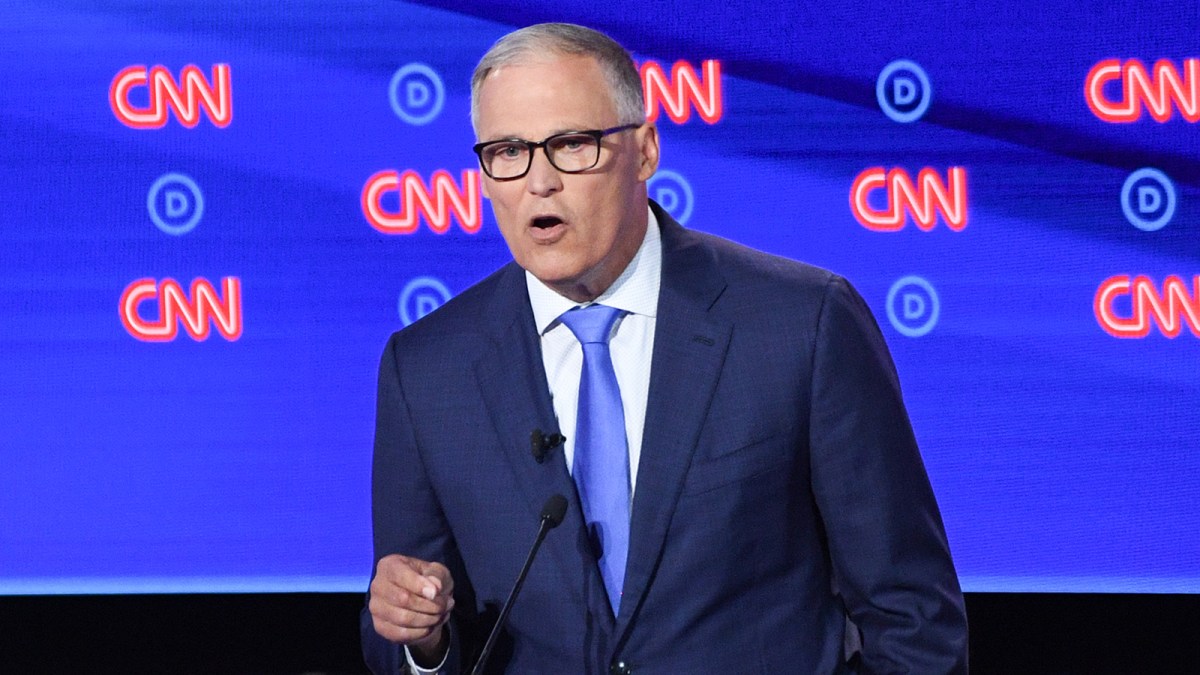

Inslee is, in fact, the ‘climate candidate’

On night two, when Inslee took the stage, it was clear that he intended to ensure climate was featured front and center. He was the only candidate to mention it in his opening statement. “It has to be our top priority,” the governor said. “My plan is one of national mobilization, quickly bringing 100 percent clean energy to Americans, creating 8 million good union jobs.” And he dedicated his entire closing statement to the topic as well. (Only two others, Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard and Senator Michael Bennet, concluded by mentioning environmental issues.)

Jay Inslee Jim Watson / AFP / Getty Images

Many on stage seemed to defer to Inslee as the climate expert — and it’s hard to fathom anyone being anointed in such a way on other major issues like, say, health care or the economy.

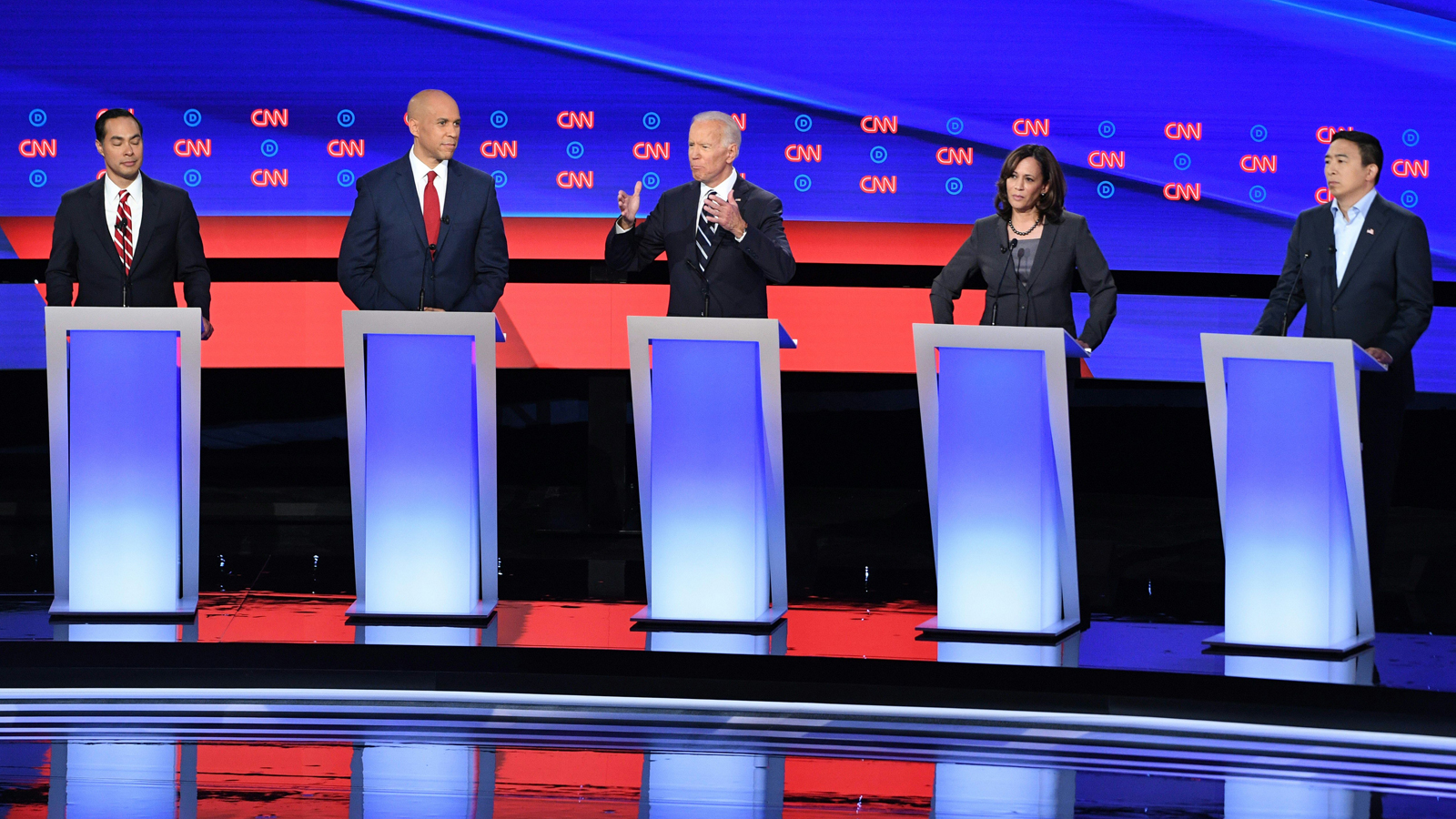

When CNN debate moderator Dana Bash began the set of questions on the “climate crisis” — note that CNN used the term as opposed to “climate change” — she immediately turned to Inslee, asking him what he knew about global warming that his rivals didn’t. When Bash later asked Senator Kamala Harris to comment on Inslee’s call for urgency on the issue, Harris immediately echoed the governor — even going so far as to reference part of his stump speech.

“I’m going to just paraphrase one of your great sayings, Governor, which is we currently have a president in the White House who obviously does not understand the science,” Harris said. “He’s been pushing science fiction instead of science fact.”

New Jersey Senator Cory Booker’s first comment on the topic also involved giving Inslee props, adding that Greenpeace ranked them as the top two candidates on climate. Inslee responded by flexing his own number-one Greenpeace ranking.“Second, Cory, second, but close,” he said. “You’re just close.”

“Thank you, man,” Booker said to Inslee. “I’ll try harder.”

Environmental justice has a moment

Even though she shared the stage with Sanders and Warren, two progressives who have made equity a central part of their platforms, Marianne Williamson was the only candidate on Tuesday night to discuss climate justice. And that’s despite the second round of Democratic debates taking place about an hour away from Flint, Michigan. “We have communities, particularly communities of color and disadvantaged communities all over this country, who are suffering from environmental injustice,” Williamson said in response to a question about Flint’s water crisis.

On night two of the debates, Inslee discussed his visit to a neighborhood in Southwest Detroit that a 2010 University of Michigan analysis called the state’s “most polluted.” The Washington governor blamed air pollution from a nearby oil refinery with boosting the area’s asthma rates and seeding cancer clusters. “It doesn’t matter what your zip code is, it doesn’t matter what your color is, you ought to have clean air and clean water in America,” he said, as Bash tried to interject as moderator.

Both Inslee and Harris rolled out climate justice-related plans earlier this week. But while the governor worked environmental justice issues into his speaking time on the debate stage, Harris was mum on the issue. Meanwhile, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio was prodded to answer for elevated blood lead levels found in children living in the city’s public housing. And Julián Castro talked about his work getting water filters to Flint residents during his time as President Obama’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

Yang talks adaptation

While candidates on both nights of the second Democratic debates unfurled plans to bring down carbon emissions, ex-nonprofit CEO Andrew Yang opted for some real talk. “The United States was only 15 percent of global emissions,” he said, repeating a line former Vice President Biden had just uttered. “We like to act as if we’re 100 percent. But the truth is even if we were to curb our emissions dramatically, the Earth is still going to get warmer.”

Yang went on to say that efforts to combat global warming are a decade late, arguing that while trying to curb emissions, we should also move communities to “higher ground” — the only mention of climate resiliency either night. “The best way to do that is to put economic resources into your hands so you can protect yourself and your families,” Yang said, seeming to allude to his proposal for a $1,000-per-month universal basic income.

Forget Paris

Several candidates on night two were quick to mention the Paris agreement, with Harris, Biden, and Gillibrand all proclaiming that they’d rejoin the accord within the first 100 days of taking office. This was a popular (and successful) talking point for many candidates in NBC’s first round of debates in June, and at first, it seemed candidates would once again go down the line picking that low-hanging policy fruit.

Enter Cory Booker, who slammed that approach as small potatoes: “Nobody should get applause for rejoining the Paris climate accords,” he said, to hearty applause. “That is kindergarten.” He went on to say that everything America does, from trade deals to foreign aid, needs to be tied to fighting the climate crisis.

And from there, the debate moved on to the next topic, marking roughly 12 minutes of climate talk on each night. It wasn’t the full climate debate that activists have pushed for, but there was certainly more substance than we’ve seen in the past.