It’s time we moved on to something else, or this is going to kill us. Not only are world oil supplies running out, but what oil is still left is proving very dirty to obtain. We need to kick our oil addiction now if we expect to preserve any hopes of economic prosperity, or unspoiled habitats.

“This is what the end of the oil age looks like.”

We have the Deepwater Horizon oil spill now precisely because the easy to obtain oil is already tapped. You don’t drill in mile deep waters if you have somewhere else you could go. The worst is yet to come. If we don’t kick oil now, we will see more disasters as oil companies move to the Arctic offshore, clear more forests for tar sands, and rape the American West to develop oil shale. Worldwide droughts, floods, and dead seas will also ensue from global warming caused from burning oil.

Richard Heinberg of Post Carbon Institute said it best: “This is what the end of the oil age looks like. The cheap, easy petroleum is gone; from now on, we will pay steadily more and more for what we put in our gas tanks—more not just in dollars, but in lives and health, in a failed foreign policy that spawns foreign wars and military occupations, and in the lost integrity of the biological systems that sustain life on this planet. The only solution is to do proactively, and sooner, what we will end up doing anyway as a result of resource depletion and economic, environmental, and military ruin: end our dependence on the stuff.”

I said in my recent peak oil article “The End of the World as We Know It” that we need to adapt to peak oil, but we can do that. This article explains how.

How do we use oil?

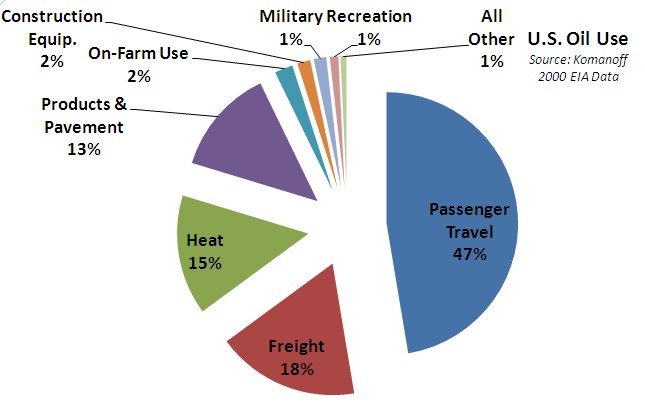

To know why we are addicted to oil and where we might most readily save it, we must know how we use it. The U.S. Energy Information Administration publishes data on oil use, yet typically in broad categories such as commercial, residential, industrial, and transportation. In a seminal 2002 work Ending the Oil Age consultant Charles Komanoff poured over thousands of lines of raw Energy Information Administration (EIA) data to get more detail on our actual end uses of oil, shown below:

Author’s graph from Komanoff data

Author’s graph from Komanoff data

What is no surprise in the above graph is that transportation — for air and land Passenger Travel (47 percent) and moving Freight (18 percent) — used 65 percent of all U.S. oil use in the year 2000, about the same as today. Our biggest challenge is clearly transportation, which I will discuss below. However, Komanoff’s detailed work showed there are big opportunities to cut oil use, where it simply does not have to be used at all.

Non-essential uses of oil

There are many ways to produce heat. In an oil-constrained world, we must move to other energy sources — natural gas, solar, and electricity — to heat buildings and water, provide industrial process heat, to generate electricity, and to run oil refineries. Komanoff found that in the year 2000, fully 15 percent of all U.S. oil use was oil burned to produce heat for these end uses.

Buildings. According to EIA, today there are still about 8 million homes, mostly in the Northeast, that use heating oil, as well as many older commercial buildings. This use of oil should be completely eliminated through conversion of all oil-heated buildings either to natural gas, or to efficient ground source electric heat pumps.

Over 30 years since the Arab oil embargo, these buildings have yet to be converted. Clearly, more direct action is needed — a requirement that buildings cannot be resold without conversion off oil. This conversion-off-oil requirement should be part of a broader requirement that all buildings must have an energy upgrade to implement life-cycle-cost-effective energy measures at time of sale. To finance these upgrades, lenders should be required to fund cost-effective energy upgrades without affecting buyer qualification. Saving on energy bills actually helps borrowers afford their loan payments.

Of course, if older buildings have to do energy upgrades, Congress must insure we stop building new buildings wrong. The House Energy and Climate Bill’s new energy building codes would do just that.

Energy savings throughout the economy, such as through better building codes, will be needed to free up natural gas and electricity resources. This can then allow oil users to switch to these other fuels without overly straining supplies and prices.

Process Heat. While industry has slowly reduced its use of oil for process heat, oil is still used extensively and hence there are still opportunities to eliminate this use of oil. Even oil companies have been open to using solar energy to provide high-temperature steam.

Electricity Generation. Today about 1 percent of total U.S. oil use is still burned to generate electricity. This is primarily in the Northeast, the Southeast, and Hawaii. Solar resources, which are well timed to shave peak demand, may cut oil used to generate electricity at peak times even in areas with no natural gas infrastructure.

We have met the enemy: oil used in transportation

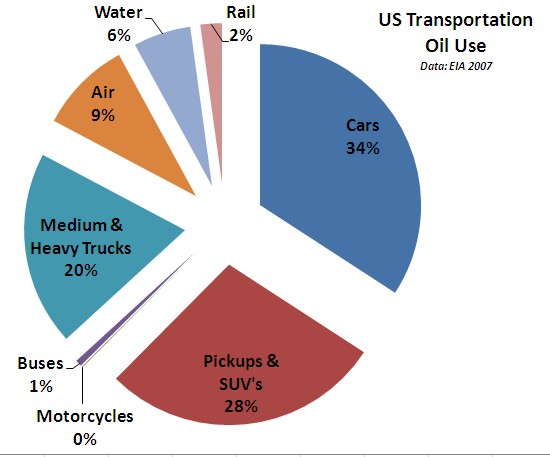

EIA data show in 2007 the U.S. devoted over 2/3 of our oil usage to transportation, in the ways shown below:

Chart by author using data from EIA, 2007

Chart by author using data from EIA, 2007

It is us!

The lion’s share of oil use in the U.S. is for transportation, and the lion’s share of that is just to move ourselves around. The oil used for cars, pickups, and SUV’s is for moving people. Komanoff found that 85 percent of the oil used for air travel was also for people, as opposed to air freight. All told, therefore, about 70 percent of transportation oil use (not counting the heavy pickups over 8,500 GVW included in the “medium to heavy trucks” category) is our use of vehicles to move our bodies from one place to another. That’s almost half of total U.S. oil use. It really is us.

Good news and bad news

That’s good news and bad news. The bad news is that it’s personal — we have to change what we drive.

The good news is that it’s possible. It really doesn’t take a Hummer or F250 to move people around. We all know someone with a Prius who gets 50 mpg and loves their car. That’s about twice the average fuel economy of the U.S. passenger car and light truck fleet today, just using existing technology.

Super-efficient cars coming

Later this year, and not a moment too soon, GM will introduce its new Plug-In Hybrid Chevy Volt, and Nissan will begin delivering its all-electric car the Leaf. European automakers have also begun marketing efficient diesels to the American market. The sampling below shows a little of what is happening:

Town Car. The Nissan Leaf is a “town car”. It runs strictly on electricity, with a designed 100 mile range per battery charge, to calm trip anxiety about running out of battery power. It costs $32,780 before a $7,500 tax credit is subtracted. Some states also have electric vehicle tax credits to further reduce the cost of the car. Will it sell? Nissan just announced its first year U.S. model run of 13,000 Leafs is already 100 percent pre-sold.

Town & Country Car. The Chevy Volt is designed to go 40 miles on electric charge only, so most days drivers won’t use any gasoline at all. When the battery runs down, the gas engine kicks in to recharge it, so you can just keep going if you want to take the Volt on a trip. You pay more for this flexibility — the Volt’s price is expected to be over $40,000 before tax credits. Yet, a “town & country” car that averages over 100 mpg of gasoline is revolutionary.

Clean Diesels. As anyone who watched the last Super Bowl knows, German auto manufacturers have their own solution to increased fuel economy — super efficient diesels. For instance, the Audi A3 TDI featured in the Super Bowl “Green Police” spoof advertises 42 mpg highway mileage.

Errand Vehicles. The Zapcar is simply interesting. It is a 4-seater classified as a 3-wheel motorcycle. At only about $12,000 (minus half that in tax credits), this is a cheap car to own. I talked to the car’s owner, and she said her Zapcar will go 40 mph top speed, for about a 20 mile range. The rooftop solar panel actually contributes significantly to its charging. It has a small heater but no A/C. If you liked the original VW Bug, you might like this.

Standards to increase efficiency of U.S. vehicles

On April 1, the EPA announced increased Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards through model year 2016. On May 21, President Obama further directed the EPA to update standards for light duty trucks and passenger cars for later model years, and for the first time set fuel economy standards for new medium-to-heavy duty trucks.

If you’ve wondered how automakers have been able to meet CAFE standards but still sell giant pickups, consider the “Medium-to-Heavy” trucks which will now be regulated for the first time. This category includes not only 18-wheelers (which may achieve a 25 percent increase in fuel efficiency with current technology) but also “medium-duty” trucks such as F250’s and Hummers, which had been exempt from economy standards as they exceed 8,500 GVW.

Using normal turnover rates, these new standards have been projected to increase new vehicle efficiency by up to 30 percent by 2020 and up to 50 percent by 2030.

Will change happen fast enough?

The fuel economy standards are a minimum for new vehicles only. However, they may not bring change fast enough to stave off serious effects on the economy if world oil prices spike soon, and consumers do not replace their old vehicles fast enough.

The U.S. has a vehicle fleet of over 240 million cars and trucks, with sales of roughly 10 to 14 million per year. At normal replacement rates, older vehicles remain in use around 20 years.

Cash for Clunkers

One popular Idea to accelerate efficiency is a renewed “Cash for Clunkers” program. It can be powerful because it requires gas guzzlers to be scrapped. To be worth doing, a renewed program should require at least a 40 percent reduction in fuel use for the new vehicle compared to the scrapped clunker. Note that percentage reduction in fuel use (rather than mpg increase) saves more fuel, and would also leave higher-mpg older vehicles still in the fleet for used car buyers.

To pay for a renewed Cash for Clunkers campaign, a “Feebate” program might apply where new vehicles with lower mpg would be assessed a Fee based on poor fuel economy. All the funds collected from these gas guzzler Fees would be immediately Rebated — hence Fee-Rebate or “Feebate” — to buyers of more fuel efficient vehicles.

The “truck testosterone” factor

The wild card in reducing our personal oil use is the love affair Americans have developed with giant pickup trucks and SUV’s. Led by decades of advertising from Detroit, these vehicles have gained steadily in market share, vastly increasing our nation’s oil use.

There simply is no Prius Hummer or F350 Volt, nor is there likely to be. The laws of physics dictate against super-efficient mileage for such heavy vehicles.

The laws of the U.S. Tax Code, however, still dictate that business owners must buy a truck over 6,000 Gross Vehicle Weight to qualify for tax write-offs. This insanity in U.S. tax law must be fixed, as there are 25 million small business owners in America who often set the social norms for others. The “boss’ car” is now a heavy truck.

Those who don’t really need a big truck should do the patriotic thing and haul their bodies around more efficiently. Leave the big truck at the work site where it’s really needed.

What about the macho factor? A leather jacket and a hot electric motorcycle bring just as much respect from the guys, and you don’t have to ask an American soldier to die to fill your tank.

What next? These more efficient vehicles can help us get through the next couple of decades, but beyond that, we will need to move almost completely off oil for our transportation needs. Measures to combat global warming call for an 80 percent reduction by 2050 in our carbon emissions — and the peak oil supply curve looks to fall almost as sharply.

Start workin’ on the railroad all the live-long day

My generation (Baby Boomer) sits on a cusp of history. Within our own family histories, we can look back at a time before the Age of Oil, and look forward to see its end. It’s really not all that long.

My grandfather grew up in a world before air travel, and the affordable personal vehicle was unknown. Yet, steel rails connected the country, and the leaders of America’s largest cities already understood that a city needs a subway system to prosper. Almost all long-distance travel and freight hauling was by rail.

I look at my one year old grandson, and I realize he will see the end of the Age of Oil. He won’t need to ride a horse to get around, as we now have electric cars for local use. Yet, there won’t be any electric airplanes, and we need to save what little oil we will have left to use as feedstock for essential products, construction and farm use, national defense, and intercontinental air travel.

We will need the steel rails once again to perform virtually all long-distance freight hauling and travel.

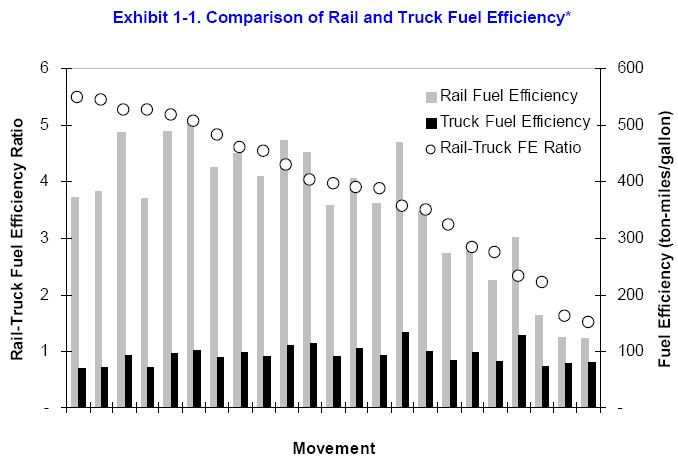

Freight Hauling. It already makes sense to move long-haul freight off the roads and onto the rails. Federal Railroad Administration studies have shown rail freight is 2 to 5 times more fuel-efficient for the same routes as long-haul trucking.

Comparison of rail and truck fuel efficiency

Source: Federal Railroad Administration

Source: Federal Railroad Administration

We need to move the big trucks off the highways anyway, or we will all pay much higher vehicle registration fees and gas taxes.

Essentially all road damage other than weathering is caused by heavy trucks, yet the bulk of road costs are paid by drivers of personal vehicles. One 40 ton truck can easily cause as much damage to roadways as 60,000 cars. This has always been a massive subsidy from drivers of personal vehicles to heavy trucks — and it’s about to get worse.

It’s going to get ugly as we choose to use less fuel, because we now pay for road maintenance primarily with gas taxes. Highway officials nationwide are already calling for higher fees and gas taxes as they see we will now use much less fuel, or no fuel at all, for our cars.

Drivers need to stand up to this and insist that trucks pay the higher costs for the damage they do, If tolls are set, they should be levied on the vehicles that inflict the damage. This will change the economics to move more freight onto the rails.

There is no downside to ending the subsidy of truck freight — our roads will be safer and less congested, road maintenance costs will go down, and our nation will create jobs by saving on imported oil.

Rebuilding the Rail Network. Though we spent our nation’s resources to build the rail network, railroads have been ripping up track for decades as they were unable to compete with subsidized truckers.

When I was the finance manager of the Iowa Railway Finance Authority, Iowa worked hard to maintain its essential rail branchline network, as did many other states. However, many lines were ripped up across the nation, and we may now need to rebuild them. The highest priority will be improving and double-tracking railroad main lines, while branch lines to key areas may also need to be rebuilt or refurbished.

Electrifying the Rails. The rest of the world is in the process of electrifying their rail lines, yet the U.S. has barely begun this task. Railroads can be even more energy efficient with electrified lines, as locomotives can be lighter and more powerful. Regenerative braking downhill feeds electricity into the grid to help power locomotives climbing up the other side.

Most importantly, an electric railroad network would not be reliant upon oil. America’s own resources of solar, geothermal, hydro, and wind power can move it. Railroad rights of way could even work in concert with renewables, e.g. to provide transmission corridors and millions of acres which could be covered with solar PV.

High Speed Passenger Rail. There will be no electric airplanes, and the hydrogen fuel economy seems always to be 50 years away. In a few decades, it may even be hard to take a Prius or Volt on a long distance trip as oil supplies shrink.

Americans may be surprised to see how far behind the U.S. is compared to other countries. Nations who are spending hundreds of billions to implement electrified high speed passenger rail networks. include not only Japan and the European Union but also China, Argentina, South Korea, and Taiwan. Passengers travel in quiet and comfort aboard high tech trains zipping along at breathtaking speeds over 150 mph.

Truly high speed passenger rail is a challenge, because it typically requires its own dedicated tracks separate from freight rail lines and grade-separated from road traffic. High up-front costs mean government must be involved, as with all other transportation modes.

American high speed rail may finally be ready to roll out of the station, however, as the Obama administration stimulus package included $8 billion for several high speed rail projects. The Florida project linking Tampa-Orlando-Miami is the most “shovel-ready.” We need to fully fund — and complete — several U.S. projects now to prove HSR is real.

We have a long way to go, but the rail lines offer a secure path into the future if we keeping a-workin’ on them.

Adapting is what we do

Actions we take now to kick our oil addiction can help us adapt to a world of shrinking oil supplies. It will be very tough, as we have waited far too long, complacent with the way we now live.

The way we now live, however, is destroying our world, as the BP oil disaster has shown. The next shoe to fall will be peak oil, which will slam our economy to the ground if we remain oil-dependent.

Those whose vision of the future assumed that everything would continue the way it has been, will not get what they want. Yet, we can adapt — that is what humans do best.

We just need to remember the famous motto of adaptation: You can’t always get you want, but you can get what you need.

This article originally posted at www.EnergyEconomyOnline.com.