What do you see when you imagine a zero-carbon future? Electric buses zipping by? Rolling hills covered with solar panels? Offshore wind farms towering over the sea? If batteries are part of your vision, good thinking. But there’s a promising, if whimsical, piece of the renewable energy puzzle that might be missing from your mental picture: the world of gravity energy storage.

When the grid depends on clean but sporadic natural resources like wind and the sun, we’re going to need ways to capture any extra energy they produce so we can use it later. Lithium-ion batteries help solve that problem, but they have limitations. They degrade over time, and they aren’t suited to store energy for months-long periods, like a seasonal stretch of gray skies or motionless air.

Enter gravity energy storage. Generating electricity using gravity is hardly a new concept — think of your classic hydropower plant, which captures the energy of falling water via a turbine. But some hydropower systems don’t just produce energy. A “pumped-storage” hydroelectric plant draws excess energy from the grid and uses it to pump water back up into an elevated reservoir where it can fall again. When full, the upper reservoir is like a charged battery, ready to be deployed for weeks or months at a time, depending on how much water it holds.

The United States already uses pumped-storage hydropower. In fact, it currently accounts for 95 percent of our utility-scale energy storage. But it’s tough to add a new pumped-storage project to the grid — it requires building a dam and creating new reservoirs, which are expensive and politically unpopular. Two-thirds of existing pumped-storage hydropower plants were built in the 1970s and 1980s. Only one new plant has come online in the past fourteen years.

But who needs water when there are all kinds of things we can slide down a mountain or drop off a cliff? Really, you can use almost any material for gravity energy storage, as long as it’s heavy, cheap, and you can figure out how to transport it up and down a steep slope.

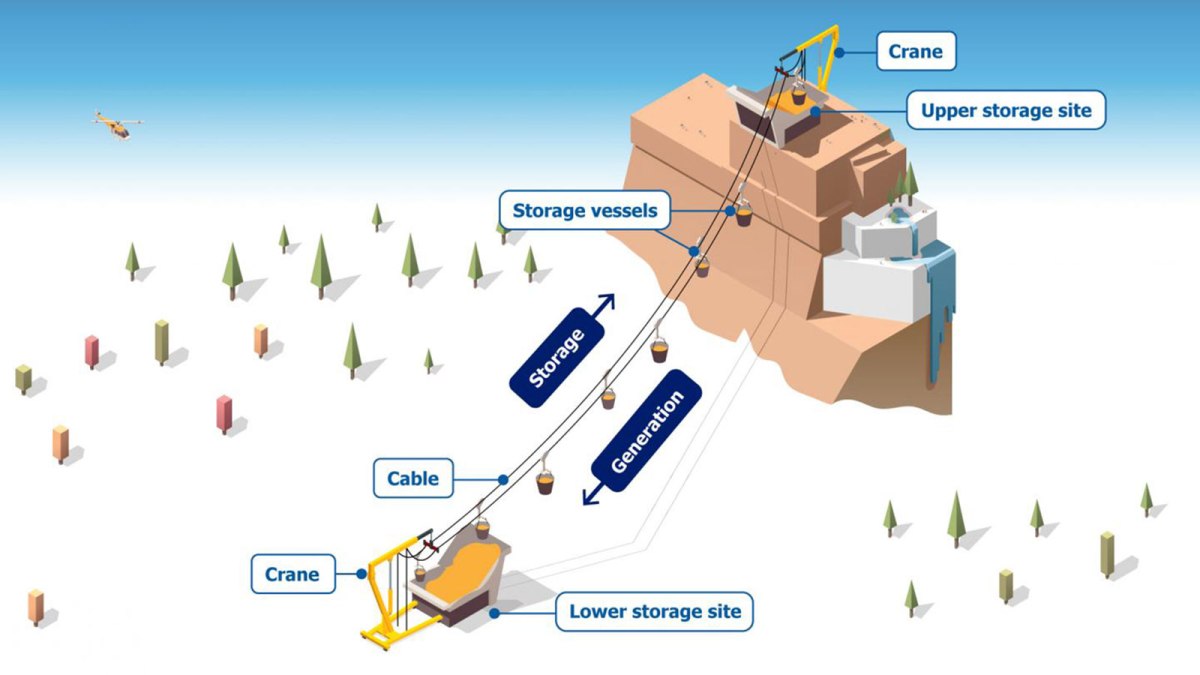

IIASA

This incredible illustration depicts a system called “Mountain Gravity Energy Storage” that was proposed in the journal Energy last week. It involves a ski-lift-style cable that carries huge bins of sand up and down a mountain. The sand gets stored in an enormous vessel at the top, and when the grid needs extra energy, it’s sent down the mountain, pulled by the force of gravity, thereby powering an electric generator. Depending on the amount of sand, the height of the mountain, and the speed of the fall, the authors estimate that it can generate electricity for anywhere from five to 555 days.

As idiosyncratic as it may seem, this isn’t a new idea. Julian Hunt, the lead author of the study and a postdoc at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, said he was inspired by a similar project that Bill Gates invested in back in 2012. “I don’t think it actually worked out,” Hunt said. “So I was trying to find ways to make it viable and trying to estimate the cost of the project.”

The Bill Gates-funded venture was a company called Energy Cache, and the model was nearly identical. The company actually built a 50-kilowatt prototype back in 2012. It got as far as entering discussions with grid operators, but never had a chance to prove it could work at utility scale. Aaron Fyke, one of the founders of Energy Cache, told Grist they couldn’t find the money they needed to keep going.

But today, Fyke said, policies like 100 percent clean energy bills and energy storage mandates in several states have made the market for storage more attractive to investors. And while there’s no ski-lift charging facility in the world yet, there are several other unconventional ideas that are much closer to becoming a reality.

Engineers have patented systems that would utilize the slopes of defunct coal mines — of which there are hundreds of thousands around the world — to haul soil, coal dust, or other earth materials to higher and lower elevations. Several companies are developing alternatives that involve dropping a heavy cylindrical weight into a big hole in the ground. Near the southern tip of Nevada, a company called Advanced Rail Energy Storage is currently building a train to nowhere across 106 acres of public land that will transport heavy weights up and down a hill. It’s expected to be operational next year.

Then there’s Energy Vault, a Jenga-like tower made of concrete bricks, perpetually being assembled and destroyed by 400-foot tall puppeteering cranes. When energy is needed, the cranes select bricks to drop down to the ground. Fyke, who’s now an advisor for Energy Vault, said the system’s advantage is that it’s modular and can be placed anywhere — it doesn’t require a mountain slope or a pit in the ground. The company is planning to construct two full-scale models in Italy and India.

The potential of gravity energy storage is almost limitless. So next time you’re lost in thought, envisioning our green energy future, don’t forget to put some ski-lifts, ghost trains, and Jenga towers on the landscape, okay?