A little after 7:30 in the morning on Wednesday, December 7, 1887, in the aftermath of remarkably strong northeasterly winds, Captain William A. Martin instructed the crew of the Eunice H. Adams, a whaling ship from Massachusetts, to anchor in cerulean water roughly 24 feet deep, close to Port Royal, South Carolina. Around 9 a.m., Charles Hamilton, a desperate crew member, jumped overboard — deserting his post, with the intention of swimming to land. He was intercepted mid-route by another ship, which returned him to the leaking brig he had tried to escape.

Later that day, an act of near-mutiny occurred. According to the ship’s logbook, a signed letter from the majority of the crew was sent ashore to Port Royal authorities. In it, the men complained that the vessel they sailed on was “unseaworthy,” unhappy with the unplanned stop and delay for repairs merely months into their voyage, in the hope that they’d be released from duty. Authorities did nothing. A sheet of rain beat down on the Eunice H. Adams, and the miserable crew was forced to continue to carry on to Cabo Verde, an archipelago on the westernmost point of Africa.

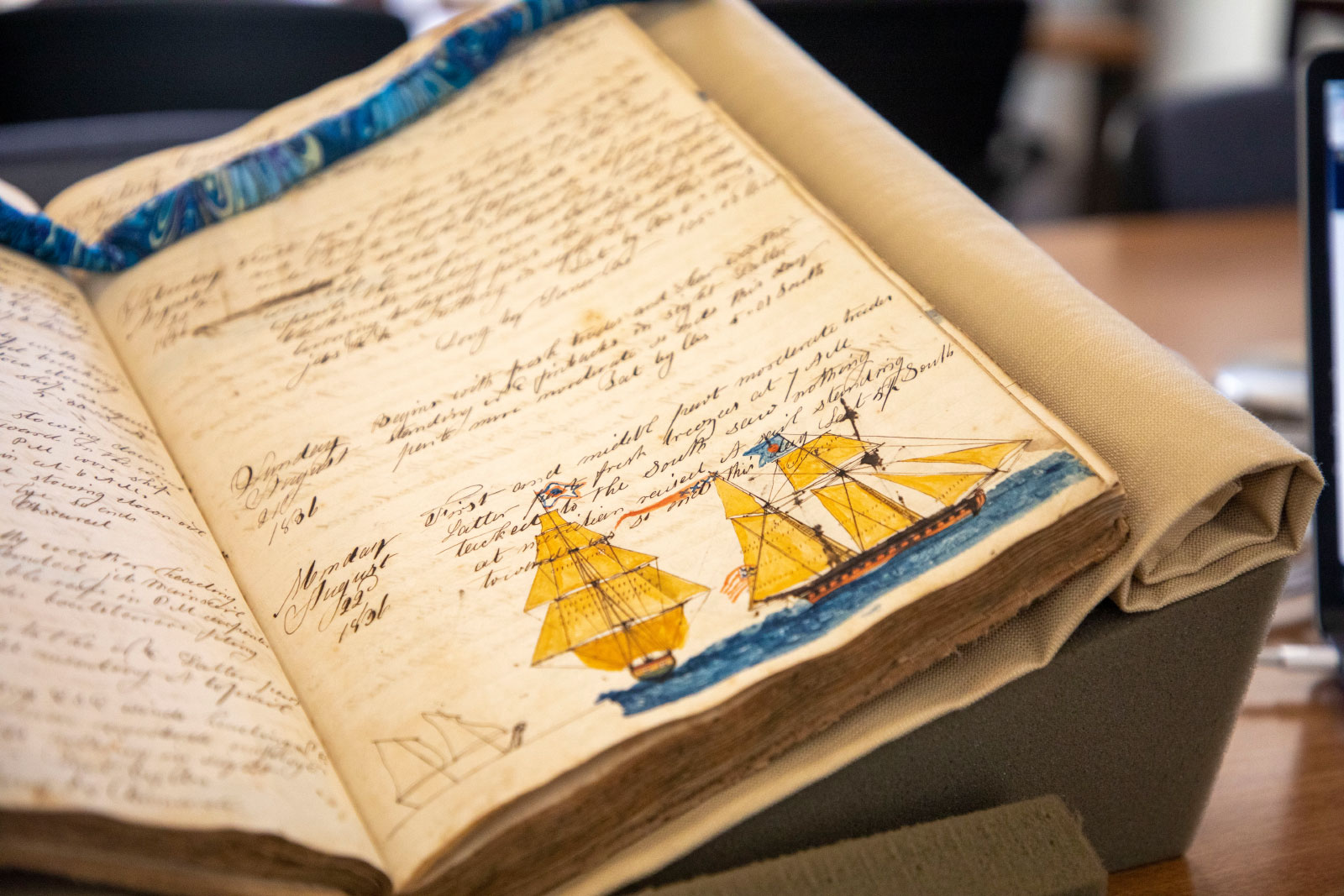

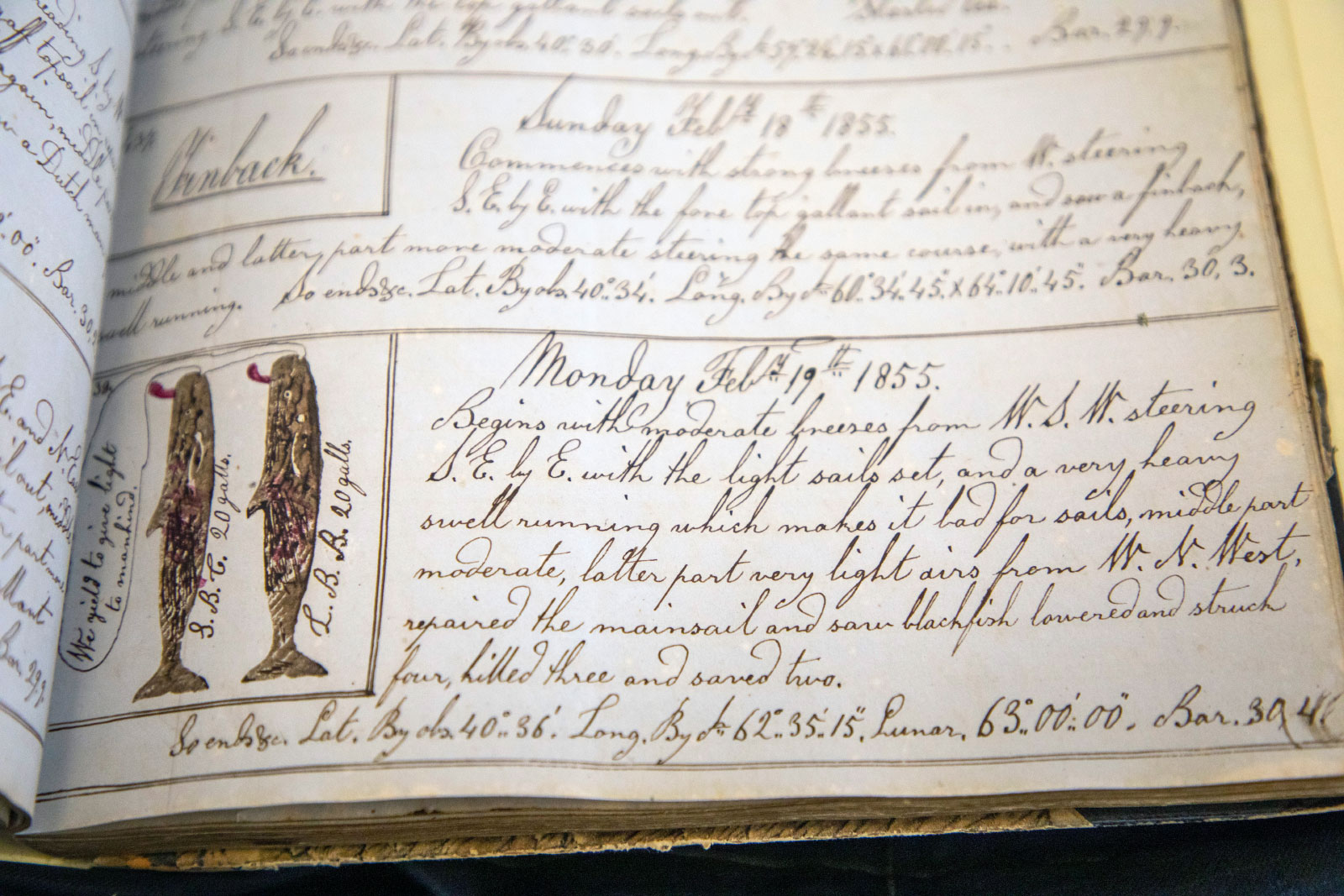

Logbooks, like the nearly 200-page document kept aboard the Eunice H. Adams, served as legal reports, necessary for insurance claims, which meant log keepers kept exhaustive records of the crew’s day-to-day exploits. They tracked the ship’s location, other vessels encountered, and both weather and sea conditions along the routes they sailed. But they also kept clues for the future: Stored within the pages of the 18th and 19th-century whaling logbooks is a cache of ancient weather records, meticulously logged by crews traversing the world’s oceans.

“One of the most important pillars in understanding how events are, or are not, changing is observations,” said Stephanie Herring, a climate attribution scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “These historical data collection efforts help us extend back the historical record so we can better see what changes might be ‘natural,’ and which we might be driving due to human influence.”

Researchers believe that these handwritten whaling logbooks could be novel guides to understanding the course of climate change. By seeing how the climate once was, they can better understand where it’s going. “This is the language of the sea,” said Timothy Walker, a historian at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. “The whaling industry is the best documented industry in the world.” Walker and Caroline Ummenhofer, an oceanographer and climate scientist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, are working with a team of scientists and volunteers mining archival documents to help inform temperature and weather models — weaving records from a nearly-obsolete industry with modern climate predictions.

Analyzing nearly 54,000 daily weather records from whaling ships, the Woods Hole historic whaling project has mined 110 logbooks to date, from a total cache of about 4,300. The data includes everything from latitude and longitude to ship direction, wind direction and speed, sea state, cloud cover, and general weather. The records are housed in private and public collections across New England, once a key hub for whaling ships returning from across the globe. Those results have been codified and added to a database that cross-compares the data points from these records with modern global wind patterns, doing things like compiling wind observations made in a specific area during a clear period of time. Large-scale wind patterns influence rainfall, drought, floods, and extreme storms — and more accurate measures of these patterns increases the accuracy of today’s forecasts.

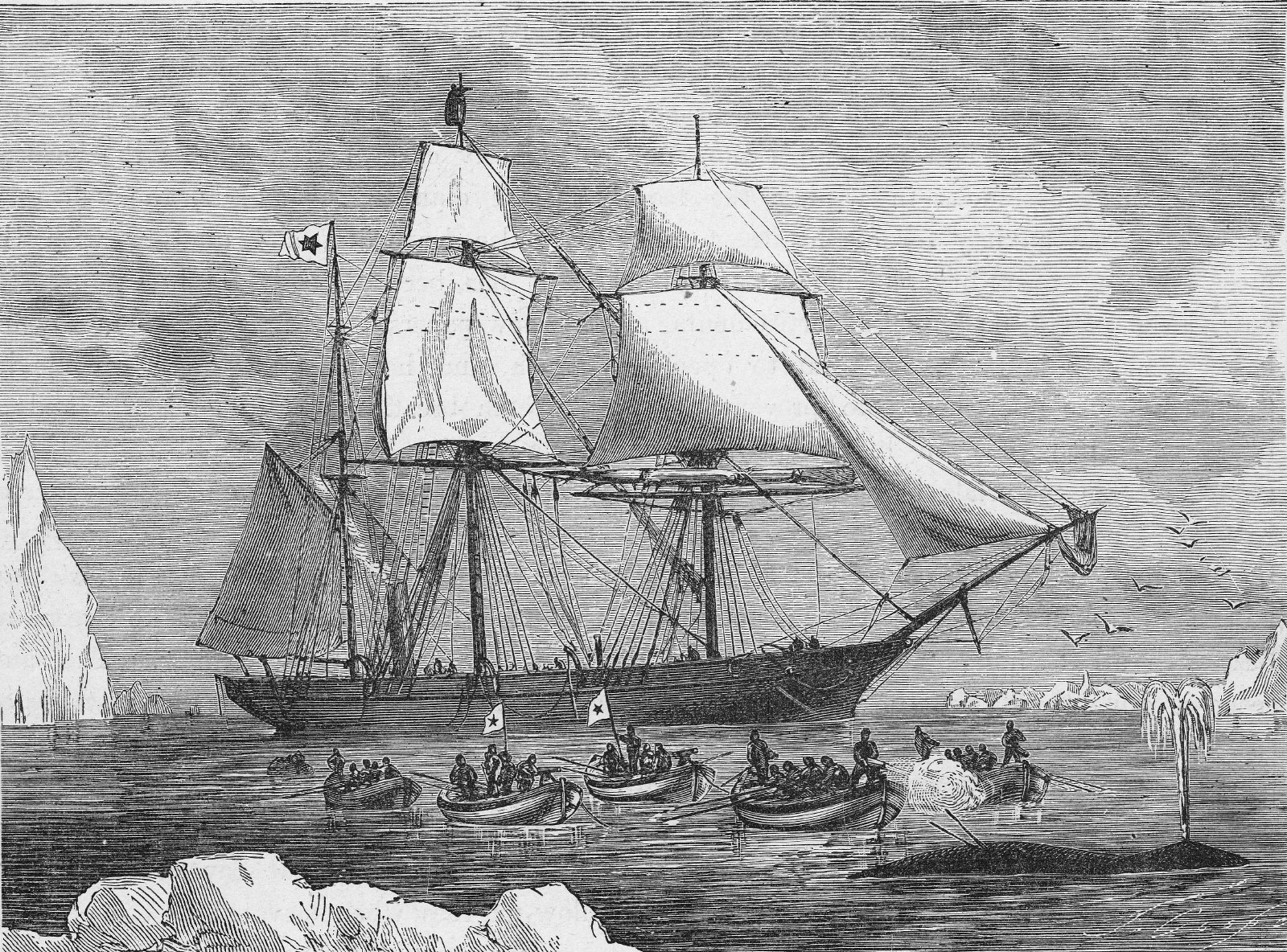

“Whalers go to places where other ships don’t go. The whalers are going out in the middle of nowhere,” said Walker. “That’s great from the perspective of weather data collection, because they’re often the only people reporting weather from 200 or 300 years ago, from the regions where they happen to be hunting whales.”

Walker says they’re currently using these documents to identify geographic ranges where the strongest winds were encountered by whalers and comparing the strength of those wind patterns in the same areas in recent years.

With that data, the team hopes to establish a baseline for long-term wind patterns in remote parts of the world where “very few” instrumental data sets prior to 1957 exist. Currently, the project is only focused on wind data, but they hope to eventually focus on other information in the logs such as rainfall, cloudiness, the condition of the sea, or whether the surface was choppy or calm on a given day. The more data points they collect, the better the accuracy of existing climate models — a 2020 study published in the journal Nature found that a lack of predictability in wind patterns above many of the world’s oceans has led to unreliable rain forecasts.

Historical records have already informed everything from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports to NOAA’s 20th Century Reanalysis Project. Resources like these not only regularly assess and communicate the impacts of climate change to better inform policy, but also produce global datasets that provide the best possible estimates of past weather conditions. (The 20th Century Reanalysis Project’s digitally accessible resources were cited in 217 scientific studies published in 2022 alone.) Through them, scientists can expand our comprehension of climate change and what’s to come.

Take the Data Rescue: Archives and Weather project, known as DRAW, for instance. Launched in 2017, the initiative has brought together hundreds of volunteers who digitally transcribe information from historical weather logs dating as far back as 1863, which are stored at McGill Observatory in Montreal. As of late, at least 456 users have contributed to that platform and transcribed 1,292,397 pieces of weather data, out of an estimated 9 million.

Then there’s NOAA’s Old Weather project, a major inspiration for the Woods Hole historic whaling logbook project. Since 2010, thousands of volunteers with Old Weather have digitally explored, marked, and transcribed logs, compiling data on more than 14 million past weather observations and contributing more than 1.5 million page images to the U.S. National Archives. They’ve analyzed everything from the Navy’s World War II records to Arctic records from whalers as far back as 1849.

In the latest phase of the project, the Old Weather team has transcribed over 1 million lines of data, where each line represents the weather for one hour of the day, and collected more than 4.6 million individual items of weather data and at least 34,000 reports of sea ice conditions.

That data transcription is mainly the work of volunteers like Michael Purves. “To me, it’s like a job,” said 75-year-old Purves, a retired meteorologist who has spent over a decade volunteering his time for the project. “I probably average at least 40 hours a week.” One of the logbooks Purves most recently worked on is from the USS Omaha, a sailing warship commissioned in 1872. He transcribes wind patterns, temperatures, and other events observed from the military ship that sailed the Arctic seas at the turn of the 20th century, and talks about the voyage as if he had been part of it — something he says many of the citizen scientists involved with the project do. “My first ship I was on was the HMS Grafton, which was a British cruiser,” Purves said. “When I joined it was 1915, and so they were taking part in World War I.”

Research collected through initiatives like these has contributed to the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set and the National Centers for Environmental Prediction Global Forecast System. It’s been used in discoveries ranging from the climate effect of historic volcanic eruptions to investigations into bird migratory patterns and the recorded time and height of water levels over a 50-year-period in the 19th century at a tidal island in the United Kingdom. It’s also been used to track weather conditions recorded during a 1939 extreme snowfall event in New Zealand.

The success of these projects is pivotal for models like the 20th Century Reanalysis Project and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast’s ERA-20C; both rely on independent, historic weather observations to form a baseline for climate research and address contemporary climate questions. Most recently, historic data has contributed to global marine heat wave forecasts and helped identify drivers behind long-term droughts in Hawaii.

The Woods Hole historic whaling project hopes to add to the growing library of historic climate data, but in contrast to a global effort like the Old Weather project, these whaling logbooks have had less than two dozen researchers assessing them. Actual results from their work don’t exist beyond illustrative examples as of yet (they expect to have definitive data to share within the next nine months), but by the time the submission deadline for the next IPCC report rolls around, the team hopes their work will help inform it and eventually be incorporated into similar datasets that use results from Old Weather.

“What we want to see is, ‘Where did the whalers experience the strongest winds? At what latitude? And was that where the strongest winds are being experienced today? Or was that further north or further south, and how has it varied over the 100 years or so that the whalers went to this area?’” said Ummenhofer.

With this work, Ummenhofer and her team aim to minimize what’s missing in climate reporting: usable information from data-sparse regions of the world.

On Monday, May 14th, 1888, as a moderate trade wind blew from the northeast between Cabo Verde and the Caribbean, the crew aboard the Eunice H. Adams killed two sperm whales found in the middle of the Atlantic.

“At 10 AM, lowered the two port boats,” wrote Arthur O. Gibbons, the vessel’s log keeper. “Larboard boat went on and struck a small whale. Soon after the waist boat went and struck a larger one,” wrote Gibbons. “Cut in the small whale. So ends this day.” Six days later, the crew caught and killed another two sperm whales.

When whaling in North America hit its peak in the mid-1800s, hundreds of ships armed with gun-loaded harpoons set off on hunts in the South Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. In 1853 alone, more than 8,000 whales were killed by American whalers, making sales of $11 million. The industry was in high demand as Americans had begun to rely on whale oil as fuel for lamps, ingredients for soap, and lubricants for everything from guns to typewriters to machinery.

There’s a curious element to using historic whaling records to inform modern climate models, records that only exist because of the commercial popularity of whaling, which drove what may have been the largest culling of animals in terms of biomass and even increased global emissions. When a single whale carcass sinks into the deep sea after death, it sequesters an average of 33 tons of CO2. This is released back into the atmosphere when whales are captured by ocean fisheries. A 2020 study published in the journal Science Advances found whaling has contributed significantly to climate change, releasing at least 730 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since 1950.

Walker is quick to point out that the global, modern, industrialized whaling industry — which operated with steam and diesel factory vessels from the 1920s until whaling bans went into effect in the 1980s — was responsible for “more than eight times as many whale captures over a much shorter period of time.” An estimated 2.9 million whales were killed worldwide in the 20th century — the majority in the Southern Hemisphere.

On Sunday morning, December 16th, 1888, a few dozen miles off the coast of the Portuguese island of Pico Azores, the most remote oceanic archipelago in the north Atlantic, a light breeze stirred the waters as the Eunice H. Adams sailed to its next destination for repairs: Horta Faial, Portugal.

Onboard, Captain Martin was up against a nearly impossible task — placating an exhausted, downtrodden crew working hard to keep the badly leaking boat afloat, all while attempting to do his job: catching and killing whales. The logbook reflects dozens of times the captain had to write to the ship’s owner requesting funds for emergency repairs needed throughout the vessel’s 29-month, transatlantic voyage.

More than a century later, a lack of funds continues to be a theme for the Eunice H. Adams, and other ships associated with the Woods Hole historic whaling project. Investing in historic projects like this one can be notoriously difficult. The DRAW project, for instance, was started in 2017 by climatologist Victoria Slonosky out of her home in Quebec and relied on volunteers to digitize the open-source project. “It is not easy to find funding to transcribe historical records,” Slonosky said.

Without citizen scientists, she estimates the scope of their project would take a single researcher around 45,000 hours of work, and cost at least $200,000 to transcribe around 4 million weather observations. A recently published study reported that more than 16,000 volunteers contributed to reviewing 66,000 sheets of historic rainfall records from the United Kingdom and Ireland — in just 16 days. Crafting blog posts and placing ads in the Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, Slonosky invited volunteers to help her transcribe. From there, the work caught the attention of researchers at McGill University before ballooning out to incorporate partners at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research on Montréal and Geothink; with the team launching a web platform devised by climatologists, geographers, archivists, data scientists and programmers. “This became an interdisciplinary project to say, ‘Come explore our records. And see how we can use these records to further our understanding of climate change,’” Slonosky said.

Like DRAW, the Woods Hole whaling project is costly in terms of time and money, and while Walker and Ummenhofer have received some funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation and private foundations, they are actively looking for more to underwrite their work. Walker sees the effort as a decade-long endeavor that dovetails whaling records in the U.S. with those stored in museums across the world. He spent the summer in Portugal setting up a collaboration with the University of Lisbon that will incorporate about 3,800 logbooks containing Portuguese naval records, spanning 1760 to 1940, into the whaling project’s purview.

“There are a lot of avenues that historians can explore, to work hand in glove with scientists,” Walker said. Whether it’s ancient medical records or port records, he sees centuries-old documentation as an untapped asset in our long-term understanding of climate change. “There is a gold mine in our backyard for finding out information on past weather patterns globally.”

The expedition of the Eunice H. Adams officially came to an end in the spring of 1890.

“The ship was leaking badly from the beginning of the voyage in October 1887 to its end in March 1890,” said historian Stephen Luce, one of the historians currently logging data for the Woods Hole whaling project. Captain Martin was a Black sea captain, Luce said, suspecting that the captain being given a leaky ship may have been reflective of racism.

Roughly one month before the Eunice H. Adams returned to Massachusetts, Martin was replaced by another member of the crew. The ship’s logbook offers no explanation. What it does offer is a look into the captain’s struggles as one of the only Black sea captains leading such expeditions at the time. “My guess is that all the better ships, the good ships that were out there, went to the white captains,” said Luce.

Luce says he doesn’t know what happened to Martin after he left the Eunice H. Adams. Records suggest that the transatlantic voyage aboard the dilapidated brig was his final journey at sea, with one account saying he fell ill and resigned of his own accord, returning home as a paralytic.

What Luce does know is that Martin died in 1907 and that he was laid to rest in a humble plot beside his wife in Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts, close to the place the Martins once called home. “I was actually thinking about visiting his grave,” said Luce.