A logger drives his freshly cut mahogany logs upriver toward Ivochote, a scratchy, low-slung jungle town in Peru’s eastern Amazon. Hoping to convert his illegal revenues into some weekend lovin’, he takes maca, a traditional Peruvian libido enhancer. He heads to a nearby brothel, but its employees are too busy protesting pollution caused by a foreign mining company to entertain him. Frustrated and ready for action of any kind, he gives up and joins an angry crowd marching to Lima to oppose the 2006 U.S.-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement, signed in April.

Far-fetched, maybe — but mahogany, maca, mining, and frustrated movements are all part of this controversial agreement, which lawmakers in Washington and Lima are preparing to ratify in coming weeks.

Bush with trade buddies in late 2005:

Presidents Alejandro Toledo of Peru and

Vincente Fox of Mexico, and former

Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin.

Photo: Whitehouse.gov/Eric Draper.

What are the environmental impacts of the Peruvian free-trade agreement? Besides ramping up international trade and investment — which can directly boost environmental damage — critics say the deal peels away social and environmental safeguards, expands corporate power, and endangers biodiversity.

It’s the same chorus of criticism that surrounded NAFTA and CAFTA. Washington’s plan for taking those models into South America was the proposed (and politically stagnant) Free Trade Area of the Americas, which attracted public ire in 2001 and has yet to be resuscitated. Rather than deal with a unified front of nations, U.S. trade negotiators have recently pushed to ink separate agreements with Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Activists are concerned about all of the deals, but in Peru the stakes are enormous. When it comes to trade worries, says Margrete Strand, a Sierra Club official in Washington, D.C., “environmentalists are unified that Peru is one of the most important countries.”

Like Ecuador — a poor country dependent on its exploitable natural resources — Peru has become a friend to extractive industries over the years. High oil and ore prices mean governments are willing to put their countries on the selling block, and their land and people suffer for it. Critics say U.S. trade policy should help ensure that resource extraction makes as little ecological footprint as possible. The new agreement, they say, does not require parties to respect international environmental accords.

Case in point: Swietenia macrophylla, or big-leaf mahogany. Though it’s covered by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species — a voluntary species-protection treaty between 169 governments, including the U.S. and Peru — activists say Peruvian officials look the other way, granting logging permits without a baseline understanding of the mahogany population and failing to enforce regulations. The secretariat of CITES has criticized Peru for failing to live up to its promises. Meanwhile, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Defenders of Wildlife estimate that most of Peru’s big-leaf mahogany exports are logged illegally, and that 80 percent of that tainted harvest winds up in the United States.

A copper mine in Tintaya, Peru.

Photo: Oxfam America.

The failure of the Peruvian free-trade agreement to force its parties to adhere to CITES or other multinational environmental accords irks greens and some lawmakers, including Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas). He has taken trade representatives to task in congressional hearings, a fact cheered by mainstream greens who say good trade law should, at the least, require adherence to environmental standards. Even better, they say, it should help build technical expertise in poor nations, so something like a mahogany count would be feasible.

A second concern is intellectual-property rights, the legal privilege granted over the products of human brain power. The new agreement is less lenient in this area — but to the benefit of the U.S., critics say. That’s where our imaginary logger’s (very real) aphrodisiac enters the picture. The plant species known as maca, Lepidum meyenii, is a member of the radish family, and a poster child for biopiracy. It grows in the harsh and lonely altitudes of the Andes and is said to boost sex drive — a fact our logger might have learned from his native Quechua ancestors. In 2001, this Andean treasure became a U.S. patent belonging to PureWorld Botanicals, Inc., a company said to have “unlocked maca’s chemical secrets.”

The Peruvian Coalition Against Biopiracy has called for the World Intellectual Property Organization to look into the matter, claiming the company violated international norms covering sustainable use of biodiversity. Marcos A. Orellana of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for International Environmental Law says the Convention on Biological Diversity — an international treaty adopted in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit — ensures “the rights of indigenous communities to their traditional knowledge in areas such as medicines and seeds.” It also mandates that they share the economic payoffs, which could steer profits from products like maca back into biodiversity programs.

The third major concern might be the most troubling. Were our logger’s imaginary brothel town anything like Cajamarca, home to Latin America’s largest gold mine, its residents would be smart to fear the aftershocks of the new trade agreement. That’s because of a provision embedded within its pages — an under-the-radar tool of U.S. trade negotiators that critics say lets foreign investors attack legitimate public-health and environmental protections.

Invested Interest

It’s known as the investor-state provision. And for a glimpse of what could happen if the agreement goes through, we need to rewind.

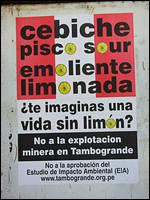

Life without lemons? A

protest poster warns of

mining’s effects on local

farmers.

Photo: Earthworks.

For years, shoddy enforcement of Peru’s already-lax environmental laws, combined with accidents, has meant big messes — and increasing outrage on the part of residents. In 2004, Cajamarca’s citizens protested plans by U.S.-based Newmont Mining to open another mine on Cerro Quilish, a nearby mountain. They said it would pollute a major watershed that feeds Cajamarca and a nearby farming valley, and took to the streets, fighting mad. Eventually Newmont, perhaps sensing that public anger would not dissipate, backed down.

Had the trade agreement been in place, says Miguel Palacin of CONACAMI — a network of Peruvian communities that lobbies for stronger mining laws — it would have put the kibosh on that kind of civil action. Investor-state provisions help protect corporations by letting them sue countries — in secret, international arbitration — for losses in anticipated revenues. In theory, Newmont could have sued the Peruvian government for untold amounts of cash for having had to abandon its plans.

In a poor country like Peru, says Palacin, such fines — or even the threat of them — could scare the government away from passing strong public-health or environmental laws that could jeopardize corporate profits. “Unbeknownst to many people, buried inside these kinds of trade agreements is a new and dramatic legal restriction on governments’ ability to function,” agrees John Echeverria, director of Georgetown University’s Environmental Law and Policy Institute. (Neither the U.S. Trade Representative nor representatives of the Peruvian government responded to interview requests.)

Like snowballs rolling downhill, the investor-state and intellectual-property rights provisions have swelled as they moved south from NAFTA, Echeverria and other trade-law experts say. Expanded thresholds in one deal become new baselines for negotiating future deals. Mainstream greens in Washington point out, for instance, that Peru’s investor-state provision is more corporate-friendly than its predecessors. A March letter [PDF] to Congress from groups including Friends of the Earth, Earthjustice, and the Sierra Club said the agreement provides foreign investors even greater rights to challenge environmental laws than does highly controversial CAFTA, approved last year.

“CAFTA gave investors the right to file suit against alleged breaches of natural resources contracts,” the letter reads. “The U.S.-Peru FTA expands these rights by broadly defining natural resources contracts to include every aspect of the extractive, productive, and marketing processes. These new rights would enable multinational corporations to attack legitimate attempts by communities to protect their health and environment even if their activities are only tangentially related to natural resource extraction.”

Critics also say the agreement makes it harder to get companies to avoid or account for mistakes, and Palacin says the deal will solidify a status quo that prefers corporate to community interests. Instead, he says, the deal should hold companies from the developed world to the more advanced environmental standards of their home countries.

A Risky Road

With half of Peru’s people living below the poverty line, and nearly 20 percent in extreme poverty, few Peruvians have the time to worry about such issues. Even if they do, it’s hard to spot the facts in the current cloud of confusion. “I don’t know it,” a weathered Machiguenga Indian near the jungle village of Camisea said recently, when asked about the deal. “They talk about it, but nobody tells me what it is.” His sentiment was echoed by others in the community.

But things may be changing. From Ecuador to Peru to Bolivia, indigenous groups that have historically been discriminated against are becoming more sophisticated and organized. They are rising up against traditional oligarchies and corporate thievery. And in Peru, the new trade agreement is emerging as a political condensation point, one that lassos disparate groups under the same cause. In fact, CONACAMI is organizing a march on the capital later this month to ask that the deal be put to a referendum.

Their proposal is backed by Ollanta Humala, a retired military colonel jockeying to become Peru’s next president in runoff elections slated for early June. Like Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who opposes trade links with the U.S. (except for his country’s oil sales), Humala is against the trade deal. Meanwhile, his center-left opponent, former Peruvian President Alan Garcia, is warmer to it, but reportedly favors renegotiation. At the grassroots level, the anti-trade agreement front — which has united labor unions, agriculture groups, students, small businesses, and transportation unions — feels Humala is the candidate most on their side, says Palacin. But he stresses that the former military colonel is a political unknown whose party lacks history and organization.

And what if the Peruvian Congress doesn’t listen to the people it represents? Will Peruvians shut down highways or pipelines like poor protestors have recently in neighboring Ecuador, where that Congress is considering a similar trade agreement with Washington? “Peruvians aren’t like Ecuadorians,” says a 56-year-old cab driver in Lima. “We don’t make as many problems when we don’t like something. But at some point the people will be tired enough to do something. Maybe this is the point.”

If there is an uprising, Palacin admits there may be a government crackdown just as in Ecuador, where officials ordered troops to knock back protestors. “There is a risk for us,” he says. “But we accept it. We don’t have any other roads to take.”