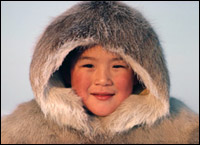

Sheila Watt-Cloutier.

Photo: ICC.

When Sheila Watt-Cloutier was growing up in Kuujjuaq, an Inuit village in far northern Quebec, summer days never got hot enough for shorts and T-shirts. Only the very brave ventured into the frigid local river for a swim. But now, she says, there are many warm days, and “the whole community goes down and spends days beaching it and trying to cool themselves off.”

Needless to say, a day at the beach is not a normal Arctic activity. The climate shifts responsible for that change are also melting ice sheets, eroding the region’s coastlines, and shrinking habitat for polar bears, caribou, and other animals the Inuit have long relied on for sustenance. While other citizens of the world debate the very existence of climate change, the Arctic is melting — and the mainstays of this indigenous northern culture are disappearing with it.

Watt-Cloutier refuses to stand by while that happens. The 51-year-old is the elected chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, a federation of Native nations representing about 150,000 people in Canada, Greenland, Russia, and the U.S. To save their homes, their prey, and themselves, the ICC is taking on the world’s largest, most recalcitrant greenhouse-gas emitter, the country the Inuit say is driving them extinct: the United States of America. The group is, as Watt-Cloutier puts it, “defending our right to be cold.”

You Say You Want a Resolution

Last November, the multinational Arctic Climate Impact Assessment startled the world with its findings that the Arctic was experiencing “some of the most rapid and severe climate change on earth.” The international press was awash with stories about the ice cap vanishing and polar bears going extinct, as well as Bush administration attempts to derail the report’s policy recommendations.

But the findings were hardly news to the Inuit. In fact, two years earlier, the ICC had begun investigating how to get industrialized nations — in particular, the U.S. — to act on global warming. They’d consulted environmental lawyers Martin Wagner and Don Goldberg, who were already working together to link climate change to human rights. The pair advised ICC that filing a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights might be the way to go. The commission, part of the Organization of American States, has no power of enforcement, but a finding in favor of the Inuit could be the basis for future lawsuits in U.S. federal courts.

“The impacts of climate change have very real, negative, harmful impacts on the Inuit’s ability to sustain themselves as they have traditionally done, their ability to be healthy, which they have a right to in the Inter-American human-rights system,” explains Wagner, of Earthjustice. “Their ability to maintain their unique culture, which is absolutely dependent on ice and snow; their ability to hunt and fish and harvest plant foods; their ability to have shelter and build their homes — all of those rights are impacted by climate change in the Arctic.”

Things ain’t what they used to be.

Photo: Government of Canada.

The Inuit had been noticing alterations in ice, land, water, and wildlife for years — phenomena that fell outside their extensive traditional knowledge. Ice formed later in the year and broke up sooner. Changes in the ice pack altered travel routes over land and sea. Experienced hunters were falling through thinning ice into seawater cold enough to kill in minutes. Once-frozen coastlines were eroding, destroying Inuit homes.

Also potentially devastating, residents were observing changes in the creatures around them, including caribou, polar bears, ringed seals, walrus, beluga whales, and seabirds. The culture has relied on these animals for food, clothing, and other materials for thousands of years. Now, increasingly, they were noticing that polar bears couldn’t find seals along the receding ice edge and were forced to scavenge elsewhere for food. A mosquito invasion drove caribou into the hills during the summer, forcing them to forsake rich lowland grazing for scrappier fare. And robins and barn owls — birds for which the Inuit had no name — appeared for the first time.

Anxious to protect life as they know it, the ICC floated a trial balloon about the human-rights petition in December 2003, at the ninth annual meeting of nations and nongovernmental organizations negotiating the Kyoto Protocol. For years, these meetings had been dominated by relatively arcane discussions on science and policy. Resistance to the treaty — at that point both Russia and the United States were refusing to sign, effectively hog-tying the entire agreement — had left many negotiators and activists dispirited. But the reaction to the ICC’s presentation was electric.

“It resonated truth for people,” Watt-Cloutier says. “And it gave a sense of energy into this process, because then it was people-oriented. It was human.” Encouraged by the response, the ICC and its lawyers continued to develop their case, and announced at last year’s Kyoto negotiations in Buenos Aires that they’d be going forward.

Once the petition is filed, possibly by the end of this year, it could take two years or more for the commission to make a determination. (Last year, 1,349 complaints were filed with the commission, 57 involving the U.S.) But Goldberg, who works for the Center for International Environmental Law, feels the ICC’s move has already made an impact. “I think the thing it’s done most dramatically is end the debate that this is a problem that’s somewhere out there in the future,” he says. “When you’re talking about … entire villages being forced to relocate … and buildings and telephone poles falling over, I think that hits people on a different level. It is very visceral.”

Culture Clubbed

Global warming is not the first industrial threat to reach this land. In the late 1980s, medical research revealed that chemicals and pollutants including chlordane, DDT, and PCBs had been accumulating in the globe’s farthest north for decades, carried from thousands of miles away by atmospheric and oceanic currents — or, as scientists have more recently supposed, by bird droppings. These persistent organic pollutants, or POPs, become more concentrated higher in the food chain, reaching unprecedented levels in predator mammals at the top like polar bears, ringed seals, beluga whales, walrus — and Inuit, who carry more than 200 toxic pollutants in their bodies.

Bad news, bears.

Photo: NASA.

This poisoning from afar means “we have to think twice about how we deal with going out into the environment,” says Watt-Cloutier, “because the environment’s our supermarket, it’s our way of getting food back to our families and to our communities.” Canadian Inuit mothers, for example, who have seven times more PCBs in their breast milk than women in the country’s largest cities, are advised either not to nurse their babies, or not to eat meat from the hunt.

The ICC was involved in years of international negotiations on POPs, culminating in last year’s ratification of the Stockholm Convention, which banned 12 chemicals termed the “Dirty Dozen.” The group is now active in the agreement’s implementation.

The Inuit have also struggled to survive a cultural dissolution common to many indigenous peoples who have experienced rapid modernization. Canadian Inuit struggle with some of the highest rates of alcoholism and drug abuse in the nation. Inuit infant mortality rates are two to three times higher than the Canadian national average, life expectancy is about five to seven years shorter, and the suicide rate is six times higher.

Watt-Cloutier says the solutions to these challenges lie, quite literally, on the ice. “The actual act of going out on the land, and the skills that are required to survive these conditions that we have in the Arctic, are the very skills … young people need to survive even the modern world,” she says. “What the land teaches you … is to be bold under pressure, to withstand stress, to be courageous, to be patient, to have sound judgment, and ultimately wisdom.

“Everything is connected,” she continues. “Connectivity is going to be the key to addressing these issues, like contaminants and climate change. They’re not just about contaminants on your plate. They’re not just about the ice depleting. They’re about the issue of humanity. What we do every day — whether you live in Mexico, the United States, Russia, China … can have a very negative impact on an entire way of life for an entire people far away from that source.”

He’s got the whole world in his land.

Photo: Government of Canada/Bryan and Cherry Alexander.

A Whole New World?

While human rights have usually been considered in local contexts — violations of a person’s rights by fellow citizens or one’s own government — the Inuit petition to the Inter-American Commission makes connections in a global context, arguing that the actions of one nation can violate the rights of people beyond its own borders. Goldberg and Wagner feel the case has the potential to transform the entire politics of global warming.

The petition is unique, says Wagner, “in that it’s making this connection between climate change and human rights. It’s unique because it’s raising an environmental claim against the United States. It’s asking the commission to recognize the international obligation of the United States for its failure to take action to protect the environment, and to recognize the implications of U.S. inaction for people both [inside and outside] the United States.”

That request isn’t sitting well with some. According to Goldberg, representatives from groups known for disputing global-warming science — including the Washington, D.C.-based, right-wing think tank the Competitive Enterprise Institute — showed up at the ICC presentation in Buenos Aires last year, asking pointed and misleading questions. “[They] were not just questioning, but were being very argumentative,” he says. The ICC also found some of its posters and fliers around the conference grounds ripped down, or slashed through with red arrows pointing at a flier denouncing the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment as “junk science.”

“I have to say, I detected a note of desperation,” says Goldberg. “These negotiations have always maintained a level of seriousness that I thought was really violated by these kinds of activities.” (A related article by CEI senior fellow Christopher Horner gives a hint of the organization’s feelings about both the case and the larger climate concerns: “Warming that would apparently not have occurred but for the United States is the turbulence supposedly imposed on this idyllic stability,” Horner writes.)

This summer, Wagner, Goldberg, and the ICC will continue gathering facts to support their case, including videotaped testimony by Inuit elders. In the meantime, Watt-Cloutier’s stature as a global activist is growing: in April, she accepted a U.N. Champions of the Earth award and helped stage a massive, Hollywood-infused “Global Warning” photo shoot on the ice in Nunavut, Canada’s Inuit territory; in June, she generated headlines from Norway when she accepted the international Sophie Prize, given annually to a recipient “working toward a sustainable future.”

She has also met with two consuls at the U.S. Consulate General in Quebec City in recent years, and testified at a hearing on climate-change policy organized by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) last September. “I am very open to talking to anyone in the State Department, or anybody else, who would like to sit down and dialogue about these issues,” she says. “I am still hoping that the United States will be able to start to change their views about how they do this.” The U.S. has not yet offered an official response to the announcement of the pending petition.

Watt-Cloutier is careful to stress that there’s no history of antagonism between the Inuit and the United States; in fact, her grandmother often told her how citizens of the southern nation saved many Inuit from starvation during the Second World War, when the U.S. military used the Arctic as a base for some operations.

“I am trying to bring back that sense of connectivity, and understanding, and responsibility,” Watt-Cloutier says. The human-rights appeal, she says, “is defending a way of life for ourselves. But it becomes the Inuit path in the human journey.”