Cluck, cluck, cluck. Bwaak!

Cluck, cluck, cluck. Bwaak!

These are not sounds I expect to hear on a stroll in my North Oakland, Calif. neighborhood — the usual soundtrack is more like thumping bass, sirens, and the rattle of fast-food paper bags. And yet chickens are pecking in backyards on practically every block, in converted sheds and rickety but raccoon-proof enclosures.

Where I live, it’s mostly a matter of economics: chicken feed is cheap, and fresh, tasty orange-yolked eggs are expensive. Around the country, though, it’s safe to say that keeping chickens has never enjoyed as much cachet as it does now. Some cities are more chicken-friendly than others: the Municode Library website can usually tell you whether your city allows chickens, how many and what sex; just find your hometown and search its code for “chickens.”

I’ve been thinking about taking the poultry plunge myself, but I decided to get some expert advice first.

If these tiny-brained feathered friends are the Boston terriers of their decade, then Gail Damerow is poultry’s Cesar Millan. In the last 40 years, she’s raised dozens of different breeds and written Barnyard in Your Backyard and several other animal-care handbooks. But she’s best known for Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens, now in its third edition. It’s the primer for all things chicken: from training your birds (yes, you can, although they probably won’t fetch for you) to keeping predators at bay to designing and building your own backyard coop. (Speaking of coops, we’re putting together a slideshow of cool coops for city chickens for Friday — if you’re proud of your poultry’s pad, send us a photo and caption!)

Gail graciously consented to answer my poultry-newbie questions by phone and email from her farm in Tennessee’s Upper Cumberland.

Q. Can chickens really thrive in a small city backyard, or do they need real room to range?

A. Chickens can get along quite well in a small amount of space, provided they have adequate food and water, and their environment is kept clean. The main issue is finding things for them to do to keep from getting bored and picking on each other (like siblings cooped up in the back seat of the family sedan). The best chicken toys involve food that cannot be eaten quickly — such as a head of fresh lettuce or cabbage hung from a string so the chickens can peck at it.

Q. How big does a coop need to be?

A. For the enclosed portion of the coop, I’d want at least 3 square feet for lightweight laying breeds such as the Leghorn and 4 square feet for heavier, dual-purpose (meat and egg-laying) breeds such as the Rhode Island Red. For the chicken run, more is always better, but total living space (indoors and out) of 7.5 square feet per bird should be adequate.

Q. Is there any advantage to having four or more chickens versus two?

A. Chickens are flock animals that like company. I think three or four would develop a more comfortable social order, unless the facility isn’t big enough for the one lowest in the pecking order to get away from others. (As long as you have at least two chickens, one is always lowest in peck order.)

Q. Can chickens and raised vegetable beds co-exist happily in a backyard?

A. When the garden is in, the chickens will need supervision so they don’t eat or scratch up emerging seedlings or peck holes in ripening strawberries or tomatoes, etc. Also for safety’s sake, fresh chicken poop should be kept away from root crops for 120 days prior to harvest, and from other crops for 90 days, although people who raise chickens (who are around chickens, handle them, clean the coop, etc.) are less likely to be affected by potential poultry pathogens from garden produce.

The Eglu Classic chicken coop holds two birds and costs an eye-popping $650, including delivery within the U.S.(Omlet US)

The Eglu Classic chicken coop holds two birds and costs an eye-popping $650, including delivery within the U.S.(Omlet US)

Q. Are people better off building a simple coop with a run, or buying one of the pricy ready-made models like the Omlet Eglu?

A. That’s a tough one. Some of the ready-made models are nice, but some look a little iffy, especially for times when chickens don’t want to be outdoors, like during several days of torrential rain or in freezing cold weather.

On the other hand, I’ve seen chicken shelters built by people who shouldn’t be allowed to use a hammer. You have to think about an awful lot of things, not the least of which is the safety of the chickens (no protruding nails, good ventilation but not drafty, insulation, predator proofing, etc.), as well as how to efficiently position the feed, water, perches, nests, and doorways. Lots of different styles of chicken coops have been designed, but none is perfect. I have lived in the same location for nearly 30 years and have lost track of how many times we’ve remodeled our chicken housing; we just finished remodeling our layer house in mid-June. People always ask me for the definitive coop design, but there is no such thing.

[Readers, if you disagree and think you’ve um, nailed it: send us a photo of your coop for Friday’s slideshow.]

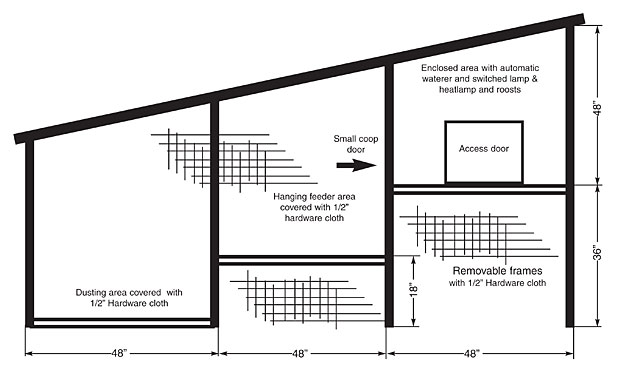

Q. Your books do, however, offer a sketch for a good workable coop.

The ideal chicken coop gives the birds enough space to get away from each other, take dust baths, and entertain themselves. (Courtesy of Gail Damerow/Storey Books)

The ideal chicken coop gives the birds enough space to get away from each other, take dust baths, and entertain themselves. (Courtesy of Gail Damerow/Storey Books)

A. Yes, on page 78 of the current edition of Guide to Raising Chickens is my concept of an ideal 4-by-12-foot stationary chicken house for a small backyard situation such as an urban one [above]. It comfortably fits four chickens of a large breed, five to six of a light breed, and up to eight small bantams. It’s completely covered and has platforms at three levels designed to prevent boredom by offering a variety of environments. The upper one-third is entirely enclosed and is where they sleep and lay; the middle one-third is open-air and is where they eat and drink; the final one-third is at ground level to provide an area for scratching and dusting (kind of like a sandbox play area) from which the chickens can be let out to roam.

We like the upper 4×4 living platform high enough to be cleaned, and eggs gathered, by a person standing up. (My husband is 6′ tall and gets tired of banging his head on low overhangs.) The upper and middle platforms have slat floors, although in really cold weather the upper platform should have a piece of plywood added to keep out night time drafts. If the two upper platforms had solid floors with bedding, the chickens could use the underneath part as a run, but the platforms would have to be cleaned often — at least once a week.

With the slats, poop falls beneath the upper and middle platforms, into an area protected by hardware cloth (also called welded wire or rabbit wire; everyone calls it something different) to keep the chicken from scratching in the poop. By occasionally tossing shavings onto the poop, odor and flies are kept to a minimum and cleaning doesn’t need to be done until the accumulation becomes offensive. The front wire panel is removable for when the accumulation needs to be cleaned out. Don’t get me started on this, but… you could easily modify this area to accommodate a worm bin.

The bottom 4×4 section might be considered a run. It could be bedded with wood chips, shredded paper, dried leaves and grass clippings, etc., but I prefer sand the chickens can dust in (they will dust in the bedding, but it’s not as good for getting rid of parasites). Chickens do need a place for dusting, so don’t forget that part in your plan.

Q. Chicken poop makes great fertilizer, I hear, once composted. How much waste we are talking about per week?

A. That depends on what’s used for bedding, how much, how often changed, etc. And also on the moisture content of the manure. A good guesstimate is approximately a pound of poop per week per chicken. Since they “go” all night long, a lot will be piled beneath the perch — in my plan, it accumulates beneath the upper platform. The rest will be spread around the run and trampled into the dirt/sand/grass.

Q. If I feed my chickens kitchen scraps, about how much grain do I also need to feed them per bird for optimum laying?

A. No grain at all, please, unless it’s sprouted. Grain tends to make hens fat, and fat hens don’t lay well. About two pounds per week of layer ration, such as Purina Layena, per hen. It’s possible to feed chickens without using commercial rations, but you would need to bone up on the nutritional properties of available feedstuffs and the nutritional needs of chickens.

Q. How many eggs will a hen lay over her lifespan?

A. Lightweight laying breeds start laying at about 18-22 weeks; others at 22-24 weeks. We’ve been talking here about the “average” chicken, but to be precise we would need to know what kind of chickens: bantams (which are very popular) need less space, eat less, and lay smaller eggs; lightweight breeds (so called layer breeds, and I assume what we’ve been talking about here), or heavy breeds, which are generally more sedate and less flighty than the layer breeds, but need more space, eat more, and lay fewer but bigger eggs.

Pullets, or young chickens, will generally lay through the first winter. After that, hens generally stop laying as day length decreases in the fall, unless provided with lighting to augment natural light for a total of 15 hours per day. So on average — again, depending on the breed, feed, and management — a hen lays about 240-250 eggs per year; pretty good would be 300 per year. After each year of laying, the number of eggs decreases and the size increases.

A caveat: fat hens don’t lay well, so an overfed hen will produce fewer eggs and will stop laying at a younger age. People with just a few hens tend to pamper them by overfeeding carbohydrates, which chickens love. Table scraps such as lettuce leaves and other vegetables are good; more than the occasional bit of stale cake or Wonder bread, or excessive amounts of grain, is bad.

Q. City dwellers are used to paying $4 to even $8 per dozen for eggs from chickens raised on pasture. Will my backyard eggs be as tasty, and will they end up being more economical, even if I opt for organic feed?

A. They will seem tastier because they come from your own hens, and they will be tastier because they’re fresher (what could be fresher than from nest to frying pan?). The economics depend on the price of the feed, how much the price can be reduced by judiciously feeding kitchen or garden scraps, and how many eggs the hens lay. Using averages, let’s do the math: A hen eats two pounds of rations per week or about 100 pounds per year, during which she lays about 240 or 20 dozen eggs. At $4 per dozen, the break-even point for the cost of layer ration would be $80 per 100 pounds. The all-natural layer ration I use costs about $25 per 100 pounds. What’s not to like about raising your own hens?