Four decades ago, when Sid Erwin began his career as an inspector at the Idaho Power Company, a string of new hydroelectric plants was pumping out power faster than locals could buy it. Soon enough, Mr. Erwin recalls, the utility began sending representatives to rural areas, urging farmers to use more electricity when irrigating their crops.

These days, Idaho’s farmers are being paid to stop using power.

Sitting at a cluttered kitchen table in his home, Mr. Erwin — now a farmer himself — waved a bill showing that last July he received a credit of more than $700 from Idaho Power for turning off his power-guzzling pumps on some summer afternoons.

“It’s a total turnabout,” says Mr. Erwin, who lives in Bruneau, about 60 miles southeast of here. “I’m almost 70 years old and this has been a lifelong education to me.”

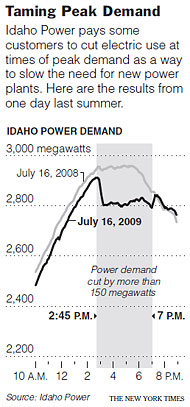

As saving energy becomes a rallying cry for utilities and the government, Idaho Power is in the vanguard. Since 2004, it has been paying farmers like Mr. Erwin to cut power useat crucial times, resulting in drop-offs of as much as 5.6 percent of peak power demand….

Other efficiency initiatives by the utility, including one promoting attic insulation, have saved about 500,000 megawatt-hours of power since 2002, according to the company — roughly equal to the amount used by 5,000 gadget-filled homes over eight years.

So begins the NYT story, “Why Is a Utility Paying Customers?“ While the world’s richest man has been educating himself on energy and then dissing insulation (!) and efficiency as a core solution to our energy and climate problems, even the reddest of red states is starting to catch on that the cheapest and greenest kilowatt-hour is the one you don’t use.

Efficiency doesn’t require siting and building new power plants and transmission, it doesn’t require waiting decades for breakthrough technology, it saves huge amounts of money for consumers and the utility, and it is a proven, scalable strategy:

- Energy efficiency is THE core climate solution, Part 1: The biggest low-carbon resource by far

- Energy efficiency, Part 4: How does California do it so consistently and cost-effectively?

- Why we never need to build another polluting power plant

But the news here is that the state pursuing efficiency and demand response is not one that is considered “green” :

“It’s clearly iconic in terms of a utility that’s turned the corner,” says Tom Eckman, the manager of conservation resources with the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, a planning group created by Congress. “They have gone from pretty much ground zero to a fairly aggressive program level.”

But the concept has rung true for Idaho’s farmers, anglers and snowbirds — outdoor types who have helped keep the state nearly free of coal plants. They have been largely receptive to the utility’s arguments that it is cheaper to save energy than to build new power plants.

“Every time they would build a plant, it would raise our rates,” says Terry Ketterling, a farmer in Mountain Home, Idaho, who grows sugar beets, corn, wheat and alfalfa and who, like Mr. Erwin, participates in the irrigation payment program.

Precisely. Most utilities can only make money selling more of their product, and if they can increase sales enough, they can put the new power plant into their rate base. After the energy price shocks of 2000 and 2001, though the utility did a 180:

Idaho Power and regulators held emergency meetings, and customers were soon hit with a temporary rate increase of about 44 percent. The utility paid big irrigators to shut down their electric pumps for the summer of 2001, figuring it would be cheaper than buying the power at high prices. An enormous phosphate plant in Pocatello was also in effect paid to temporarily shut down one of its energy-guzzling furnaces. The move hurt sales, and the company, FMC, decided later that year to close the plant permanently.

To avoid being caught short again, Idaho Power decided to give energy-saving measures a try. Another push came from the state’s Public Utilities Commission, which ordered Idaho Power in 2001 to refocus on energy efficiency — something the utility had dabbled in during the 1990s….

The utility is asking regulators to make permanent a pilot program started in 2007 that allows Idaho Power to raise rates to make up for selling less power.(This concept is known as decoupling and is celebrated by energy-efficiency advocates; Idaho was one of the first states to adopt it, after California, though Idaho Power’s large industrial customers are so far exempt from the rate adjustments.)

DEMAND RESPONSE

And guess who benefits?

PERHAPS more than any other group, Idaho’s farmers have experienced at first hand the effects of the utility’s transformation. Though Idaho’s economy has diversified in recent years, more than a fifth of its land is devoted to farming — not only to grow Idaho’s world-famous potatoes, but also crops like alfalfa, triticale and oat hay, all of which Mr. Erwin grows.

Vast amounts of energy are required to pump water up to the state’s plains from the Snake River or from wells. The largest farms can use as much electricity as several thousand homes. During the summer, big farms keep their pumps on nearly 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Until the 1970s, many farmers used gas-powered engines to force water uphill, according to Mr. Erwin. But by offering steep discounts, Idaho Power convinced many of them to put in electric pumps and use them to move water up even taller slopes; the discounts are still in effect. Irrigation accounts for 12 percent of Idaho Power’s electricity load over all — and 23 percent during peak periods.

That’s why, in recent years, Idaho Power decided that farmers could help it reduce the load on sunny summer days, when air-conditioners and other gadgets are on, by turning off their pumps for up to 15 hours a week.

This concept, called demand response, has gained traction in utility circles. In essence, it involves paying users to make small sacrifices when there is an urgent need for extra power (the “peak”). The utility can then rely on cutting some demand on its system at crucial times — and, in theory, avoid the cost of building a new plant just to meet those peak needs.

Yes, rates have to go up a little for everyone to pay for the efficiency measures, but far less than the rates would go

up to build new power plants and transmission. And everyone can take advantage of the efficiency programs to lower their total energy bill:

Ordinary consumers have also been called upon to help with efficiency. These days, most utilities enclose fliers with monthly bills that offer energy-saving tips for appliances and light bulbs, but Idaho Power seems to have taken the campaign to an extreme.

Just before Christmas, the utility bought ads in newspapers flagging “naughty or nice” holiday gifts: an electric charger for a mobile device, for example, was “naughty,” but a solar charger was “nice.” Last October, Idaho Power offered free classes to Boise residents featuring energy-saving tips for cooking (ever tried a solar oven?) and demonstrations on sealing ducts.

Another program, begun last June after a yearlong pilot version, pays individuals 15 cents for each square foot of insulation they put in their attics. “That was a no-brainer,” said Courtney Washburn, a Boise resident who works for the Idaho Conservation League and who received a letter from Idaho Power promoting the insulation rebate.

Ms. Washburn also participates in the utility’s “demand response” program for air-conditioners. More than 32,000 Idaho Power households (out of nearly 407,000 total) have allowed the utility to control their air-conditioners at crucial times.

On a hot summer day, Idaho Power can in essence push a switch that causes devices installed on participating air-conditioning units, like Ms. Washburn’s, to cycle on and off for intervals as long as 15 minutes. Ms. Washburn says she has noticed no difference in temperature, even though a sweltering day is exactly when people want their air-conditioning most. Executives say the program lowers use during peak periods by about 1 percent. Participants are paid $7 a month during the summer.

Ms. Washburn says her electric bill has dropped by about 30 percent as a result of the attic insulation and the $7 credit.

Insulation is a “no brainer.” Tell that to Bill Gates!