E. O. Wilson thinks you should get out there and make some noise.

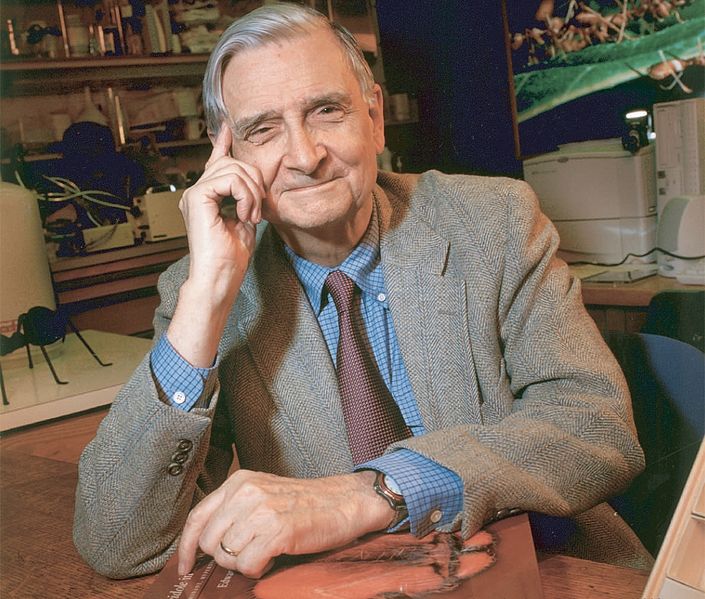

We had lots of questions for acclaimed biologist and conservationist Edward O. Wilson when he dropped by the Grist office recently while touring to promote his latest book, The Social Conquest of Earth.

But Wilson directed the toughest question of the day back at us: Why aren’t you young people out protesting the mess that’s being made of the planet?

As we squirmed in our seats, Wilson, 82, continued: “Why are you not repeating what was done in the ‘60s? Why aren’t you in the streets? And what in the world has happened to the green movement that used to be on our minds and accompanied by outrage and high hopes? What went wrong?”

We didn’t have great answers, so we’re going to turn the questioning on you, dear readers: Why aren’t you out in the streets? And if you are, where, why, and who else is out there with you? Should more of us be staging ’60s-style protests? Can online activism or lobbying in the halls of power make just as much of a difference, or more? Tell us what you think in comments below.

Now back to the questions we asked Wilson about his life’s work and his new book. Over the course of his long career as a professor at Harvard, he’s conducted pioneering research on ants, written seminal books on sociobiology and biogeography, published ant-centric fiction in The New Yorker, and led major efforts to preserve global biodiversity. His new book traces human morality, religion, and arts to their biological roots, and turns traditional Darwinism on its head, arguing that social groups and tribes are the primary drivers of natural selection.

Q. The title of your book has the word social in it. Social has become a buzzword for online networking, this new way of forming groups. Are you on Facebook? Are you using the internet to look at the way groups behave?

We are entering a new world, but we’re entering it as Paleolithic brains. Here’s my formula for Earth’s civilization: We are a Star Wars civilization. We have Stone Age emotions. We have medieval institutions — most notably, the churches. And we have god-like technology. And this god-like technology is dragging us forward in ways that are totally unpredictable.

We have not gotten beyond the powerful propensity to believe our group is superior to other comparable groups. However, we are draining away the instinctual energy from nationalism — that’s a big help. I think we’re seeing the beginning of the draining away from the dreadfully dissolutive, oppressive institutions of organized religion. Seeing what’s happening is part of the reason for the Tea Party and the populist revolt now that has kidnapped the Republican Party. There’s a resentment about the old bonds and the old groups dissolving and new groups being formed.

Q. Have you seen concern about biodiversity decline over the last decade? A lot of energy seems to be going toward climate change and not as much toward biodiversity.

A. Isn’t that astonishing? We’re destroying the rest of life in one century. We’ll be down to half the species of plants and animals by the end of the century if we keep at this rate. Very few people are paying any attention, just dedicated groups. The only way we’ve been able to get people’s attention is through big issues like pollution and climate change. They can’t deny pollution because you can give them the taste test. You can say, “We just took this out of the Charles River. Here, drink.” But they can deny climate change. We’re in a state of cosmic or global denial.

However, there are changes. The general direction is going up the right way. The only question is how much damage are we going to do to biodiversity before we catch on. Right now I’m going to national parks around the world — I’ve been to Ecuador, Mozambique, the southwest Pacific, all of Western Europe. I’m going to write a series on national parks — what the basic philosophy of national parks and reserves should be, and how it relates to our own self-image and our own hopes for immortality as a species.

We have to do everything we possibly can. I like to tell this the way a former Southern Baptist would tell it, in the original accent. Then you’ll see what I’m trying to say when I say we have to use every weapon at our disposal, all the time, everything from science to activism to political influence, etc. So this is Billy Sunday, a pioneer in Southern evangelicalism and fundamentalism in the ’20s: “I hate sin. I hate sin so much I’m going to fight it till my arms won’t move no more. When my arms don’t move no more, I’m gonna bite it. And when all my teeth are gone, I’m gonna gum it.” Now you get the picture. We all have to do that. When there’s nothing else at hand, gum it.

Q. Some of our readers sent questions for you via Twitter. One asked, What three lessons should we learn from ants?

A. None. We learned a lot of science from ants, but, for heaven’s sake, let’s not do what ants do. Ants are totally subservient to instinctual rules. Males are produced only a short time each year, and they have only one function, which I won’t go into, and when they perform that, then they die. Also, ants are the most war-like of all known creatures. They are at perfect harmony in a colony, but they’re always at war with any colony they encounter. And furthermore, a lot of species kill and eat their injured. So let’s not go the ant way.

Q. Here’s another: What findings among all of your research still surprise and amaze you?

A. Well, after I found them, they don’t amaze me.

Q. One of our readers wants to know what your favorite ant is.

A. Aren’t some of the readers worrying about biodiversity?

Q. We got four or five variations of this question: Are we doomed?

A. I’d like to say no. I’m surely not going to be stupid enough to say yes. What I will say is: no, I hope.

Here’s my favorite little maxim. It’s from Abba Eban, foreign minister of Israel during the 1967 war, one more dumb, senseless war in the Middle East: “When all else fails, men turn to reason.”

I think maybe we are really and truly ready to start trying to solve problems for once in human history by using our forebrain.