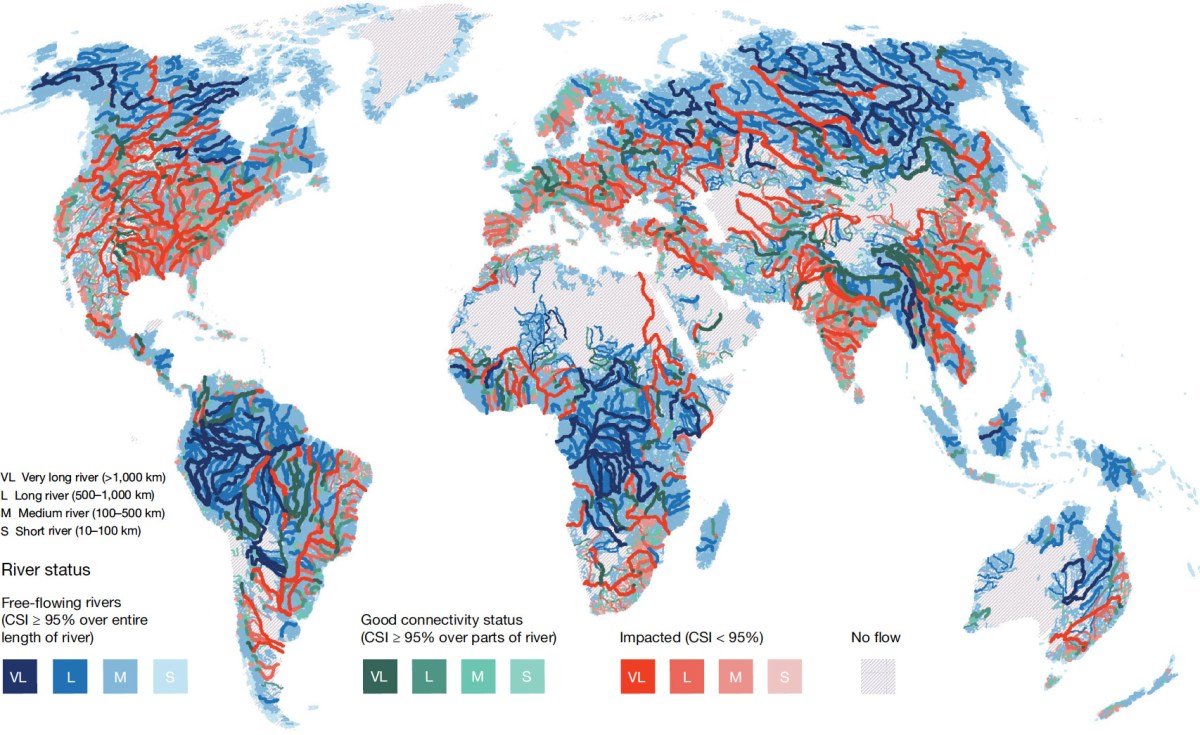

It hasn’t even been a week since the U.N. released a depressing report on biodiversity, and now, a new study in Nature shows that 63 percent of the world’s longest (at least 620 miles) rivers are impeded by human-built infrastructures such as dams and reservoirs. Dam(n).

Rivers are a key source of food and water for agriculture, energy, and humanity. They’re critical to many cultures and communities and home to a plethora of species like salmon and trout. They also bolster ecosystems by restoring groundwater and serve as a buffer against drought.

But with the increasing demand for more water, energy generation, and flood management, the construction of dams, levees, reservoirs, and other river-obstructive infrastructures is becoming ubiquitous.

“Free-flowing rivers are important for humans and the environment alike, yet economic development around the world is making them increasingly rare,” lead author Günther Grill of McGill University said in a statement. Here are a few gloomy statistics from the study.

- There are 60,000 large dams and more than 3,7000 hydropower dams currently planned or are under construction worldwide.

- The longest uninterrupted rivers are restricted to remote regions in the Arctic, the Amazon and Congo basins.

- The last two uninterrupted long rivers in Southeast Asia are critical sources of food for fisheries that provide over 1.2 million tonnes of catch each year.

- While Asia is flowing with dam installations, the Amazon, Balkans, China, and the Himalayas are facing a huge increase in hydropower construction. Other countries such as India, Brazil and China are also planning and building infrastructure that will harm rivers through dredging and building dams.

Rivers are vital to our ecosystems. But hydropower is a difficult balancing act in a planet where there’s a desperate need for more clean energy.

There’s one bit of good news. Carmel River in California is seeing a big recovery of fish populations after a centuries-old dam was removed. The demolition is considered the largest dam removal in California history. And four years later the dam went down, species such as trout and lampreys are rebounding and other tributaries are reviving.

“We don’t want to do the touchdown dance yet, but so far things are looking good,” Tommy Williams, a biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told the Mercury News. “It’s just amazing how fast these systems come back. Everything is playing out like we thought.”