James Corless is the northern California campaign manager for the Surface Transportation Policy Project. STPP works to promote better transportation and land-use planning, walkable communities, public transportation, and citizen involvement in decision-making.

Sunday, 18 Jul 1999

TRUCKEE, Calif.

For countless immigrants, it’s been reinvented time and again as the ultimate promised land. One writer calls it “America squared … the place you go to find more America than you ever thought possible.” A travel guide from the turn of the century blessed it as “a sun drenched garden spot cooled by gentle zephyrs from the sea.” Half a century earlier, similar sentiments and rumors of wealth from the earth caused the Chinese to refer to this land at the other end of the ocean as “Golden Mountain.”

Call it what you will, California is a remarkable place, equally celebrated and misunderstood, with a reputation and mythology that continue to seduce waves of newcomers. And coming they are. The nation’s most populous state is expected to add an additional 30 million people — doubling its size — in the next 40 years. This fact alone seems to influence all thoughts, all discussion about what we’re doing and where we’re going. California appears to live in the future, something that may explain why history here so often seems like a footnote in four-point font.

I introduce my newly adopted state as background music for this week’s diary. For the next few days, I’ve decided to leave the tired, old trendiness of San Francisco behind, trading in the fog, cappuccino, and sideburns for the pine-covered foothills of the Sierra Nevadas, the vastness of the Central Valley, the farm towns of the Inland Empire. Lucky for you, you’re not going to be subjected to the drudgery of my daily toils for the nonprofit group that employs me, an organization known as the Surface Transportation Policy Project. But you can still rest assured that, while I am leaving my legislative advocacy and media campaigns behind for the week, you’ll nonetheless be receiving your fair share of transportation and growth talk — that’s ’cause I’m pretty much obsessed with the topics. And there are indeed a few work-related people and places I’ll be visiting to fill you in on what I do as I navigate the backroads with my trusty pickup and my loyal companion, the dog I affectionately call “Charlie.” (Okay, alright, I’m in a Honda Civic and my allergies make pets an impossibility, besides the fact that it would defy every law of “road cool” to have a canine cooped up in a hatchback. Steinbeck would kill me.)

This opening salvo is coming to you from the laptop precariously perched on my hotel room bed in downtown Truckee. We’re in what they call the High Sierras, where the California Trail broke south from the Oregon Trail, and emigrants flooded through from the Great Basin in search of gold. There’s many a great travel story to tell about Truckee, a town that’s often associated with the tragedy that befell the Illinois Donner party just west of here as a shortcut suggested by one of the very first (and apparently overpriced) tourist guides to the region proved to be the ultimate wrong turn (I’ll bet it was Mr. Donner’s fault for refusing to ask for directions). The first transcontinental railroad blasted its way through here in 1860s with the help of several thousand Chinese laborers. This hotel still provides earplugs to block out the steady rumble of nocturnal freight trains and the occasional Amtrak rushing to make up lost time on its way to Chicago. By the 1930s, the town was characterized as “a railroad and stockraising supply center that lacks even a sprig of green.” This is part of the description in a fascinating guide published by the Works Progress Administration toward the end of the depression. Seems they employed out-of-work artists and writers to chronicle life in the Golden State, and what an account it is. Who said big government couldn’t get down with the people? Sixty years ago they promised that “Saturday nights the cheap saloons and gambling halls overflow with lumberjacks, cow-punchers, and shepherds.” Well, the vegetation’s grown back and the cowboys — unless you count the kids drinking Miller across the street in the back of their Chevy Suburban — have all but faded away.

The transportation mode du jour is of course the Interstate. Truckee’s thriving main street — once synonymous with the old U.S. 40 that truly linked every town between San Francisco and Baltimore — has now been relegated to an exit off Interstate 80 that one can take to join the 4×4’s crowding the shores of Lake Tahoe. I’m hearing this phenomenon in inverse, as Sunday afternoon slips into evening and the highway whines louder under the strain of a thousand weekenders rushing home to Sacramento and San Francisco. But not me. South tomorrow, on to Emerald Bay, Monitor Pass, Markleeville, Lee Vining, and Mono Lake. On to what Robert Louis Stevenson called “the good country … the land of our future.” Care to join?

Monday, 19 Jul 1999

LEE VINING, Calif.

I arrived in town late in the afternoon, having nowhere to stay. A slew of motels lined the central street, but against my intuition I took the advice of the park ranger I’d met just outside town and pulled up in front of the Best Western. I entered a lobby teeming with tourists. “You got a reservation?” the woman behind the desk shouted. “No,” I said, “no, I just got here.” “Oooh, well we don’t have any rooms left, and neither does anyone else in town. Nope, you’re too late, everyone’s booked.” She paused, turning momentarily toward the back window. “Unless, of course … you want the trailer.”

Now, let me be honest up front. In my line of work, we don’t generally trust state departments of transportation. And I think it’s probably safe to say they don’t care for us too much either. These guys (and I mean guys) had a lot of fun building the Interstates for four decades. But now it appears they’re stuck in a gear they can’t get out of, like a scratched old Frank Sinatra record. So when I tell you that last year the town of Lee Vining and surrounding Mono County requested that their transportation funding be spent on widening sidewalks and other pedestrian safety measures, and that they were rejected by the state and told to put the money into the highway widening project instead, maybe you won’t be surprised.

That’s part of the reason I’m here. I heard Lee Vining’s “David and Goliath” story soon after arriving in California. I had worked on the federal transportation bill in Washington, D.C., lobbying for more local control over decision-making and better long-term planning and coordination. So when grants became available for one of the more promising community planning programs that we helped get into the bill, I immediately thought of this place. What shocked me the most is that we actually helped Lee Vining win the grant, an award of $180,000 for a two-year publicly driven planning process to balance tourism with environmental protection, to help the town better serve as the eastern gateway to Yosemite and possibly the staging area for a future public transit system planned for the park, and last but not least, to win its main street back.

Tuesday, 20 Jul 1999

OWENS VALLEY, Calif.

“In the East, to ‘waste’ water is to consume it needlessly or excessively. In the West, to waste water is not to consume it — to let it flow unimpeded and undiverted down rivers.”

— Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert

Folks around the Mono Lake Basin and elsewhere up and down the highway 395 corridor refer to it simply as “DWP,” assuming you know what they’re talking about. If you live in Lee Vining, or Lone Pine, or Independence, or anywhere along the lower east side of California’s Sierras, those initials would more likely than not exact an immediate response. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power — headquartered a good 250 miles to the southwest — has left an indelible mark on both the people and the places all along the Owens River valley. For here began the first real water projects in the West, most of them the brainchildren of an Irish engineer turned Angeleno named William Mulholland.

Mulholland, driven.

At the turn of the century, the Owens Valley was reputedly an agricultural oasis, feeding orchards and farms with a seemingly endless source of snowmelt cascading off the backside of the Sierras. The Valley, though, also happened to be one of the few distant water sources that wouldn’t require a little help making it over the mountain ranges that surround Los Angeles on three sides. At more than 4,000 feet in elevation, water from the Owens River could flow to L.A. at sea level without the need for pumps and electricity, a fact that had drawn the attention of Mulholland. It was, after all, 1905; gravity was an engineer’s best friend. And so, quietly but methodically, the City of Los Angeles began buying both land and water rights throughout the length of the Valley, and one of the most memorable water wars in the history of the West began. When it was all over, some 25 years later, the enormous Owens Lake (still curiously colored blue to this day on several local maps) had vanished, as had much of the river feeding it.

Los Angeles Aqueduct.

Though, I should add, not without a good fight. As farms throughout Owens Valley began to turn a year-round brown and news spread that their precious water was actually proving to be unneeded in L.A. for the time being (instead it was being used to irrigate orchards in the little-known San Fernando Valley to the north of the burgeoning metropolis), folks got a little upset. First they diverted the open channel aqueduct back into the old riverbed. Then they did it again. Finally they began to blow things up –literally. It wasn’t until a deal was finally announced that supposedly protected a share of the farmers’ water rights that people backed down. The deal, of course, collapsed — as did the orchards up and down the valley.

For Los Angeles, the Owens Valley claim was just the beginning. The mighty Colorado was next. And soon thereafter, square in their sights, stood the waters of Mono Lake several hundred miles to the north of the Owens River source. Just two years before the diversion of the lake began, writers compiling “The WPA Guide to California” in 1939 heralded the fact that the waters would soon be put to good use. “Though it appears fresh and inviting, Mono Lake is actually a briny deep, in which nothing but one small species of salt water shrimp and the larvae of one tiny black fly can live,” they explained in the Guide. “But the water that feeds Mono Lake will not go to waste much longer, for, soon purified, it will go into the new Mono Basin Aqueduct and help to slake the thirst of metropolitan Los Angeles.”

By the 1980s, levels at Mono Lake were half what they were when diversions began in 1941. Far from lifeless, biologists had discovered rare species living in and around the prehistoric lake, not the least important of which were many migratory bird populations, including thousands of California Gulls that used the two islands in the middle of the lake as breeding grounds. Due largely to the tireless efforts of local activists organized as the Mono Lake Committee, the courts struck a monumental blow to the City of Los Angeles in the early 1990s by ordering fewer stream diversions and increased water levels in order to protect both the lake and its surrounding residents, who had to endure noxious dust storms as a result of receding waters.

Of course, this is still California, where the past is reinvented on a daily basis and we can’t resist reducing history into a feel-good saga to soothe the senses. The 1939 “WPA Guide to California” makes no mention of the local uprising a decade earlier that for a brief time turned the towns straddling U.S. 395 into veritable police states. Some 30 years later, though, Hollywood did decide to make a movie based on the battle over water rights, which had consumed the very same towns that ironically became movie sets for the countless westerns being turned out by the studios. The 1950s looking back at the 1920s, a curious thing unto itself, made all the more surreal by the actor chosen to defend the needs of a thirsty metropolis and the role of progress, knocking some sense into those unruly and restless Owens Valley rednecks: John Wayne.

Learn more about the ongoing efforts to preserve Mono Lake at http://www.monolake.org.

Wednesday, 21 Jul 1999

BAKERSFIELD, Calif.

“People come to Bakersfield to work, in the oilfields and on the farms, because that’s just about all there is.”

— Roger Neal, quoted in The Great Central Valley: California’s Heartland

Old Bakersfield, Calif.

The trucks aren’t letting up. Only the air conditioner can drown out their roar as they take turns shaking the walls, a gentle reminder that I’ve crossed back over the Sierras and landed along the outskirts of Bakersfield on Highway 99. Which wasn’t my plan — to be on the outskirts, that is. I’m a sucker for downtowns and old hotels, and had my hopes up when enormous building-top art deco letters promised the “Padre Hotel” as I entered the city center this evening. The hostelry, advertised as “the finest hotel west of the Rockies” soon after its completion in 1928, was nonetheless closed for business, unless I felt like grabbing a cocktail in a darkened corner of the ground floor “Town Casino.” In keeping with tradition, though, the “Vacancy” sign was still lit up on not one but two sides of the hotel’s fading Spanish Revival exterior. A little further up H St., the grand old Fox Theatre had just fired up its Las Vegas-style neon marquee, promising fame and fortune for the children descending on the venue en masse in their shiny green unitards, butterfly wings, and mouse ears, preparing to perform “A Tribute to Disney,” no doubt to the delight of countless parents.

Tempting though it was, I opted out. It just didn’t seem like something one does alone. Unlike eating, of course, which is something I had managed to accomplish alone routinely without any trouble — until tonight. “Just one?” inquired the waitress. “Not waitin’ for someone else?” No, no, “just me,” I explained, almost apologizing, as I slid into an oversized booth. She smiled. “Just passin’ through, are you?”

New Bakersfield, Calif.

Which, of course, was a fair comment. People have been passing through here for years. The Okies were by far the most famous, but the Chinese, Koreans, Swedes, Salvadorans, Hmong, Mexicans, Germans, a

nd even the Basques came too. Today Bakersfield is one quarter Latino, a percentage that is expected to increase dramatically, as is the city’s population overall. But it seems that its many residents, at least tonight, aren’t wandering the streets downtown. Indeed, I can’t get over the absence of this city in its historic core. It’s been surgically removed, more so than in any other urban area I’ve seen in California.

Combine this with my drive into town through Oildale (“more derricks than you can shake a stick at” I’m guessing was a close runner up in the city slogan contest), and I started thinking that the San Francisco snobs — so famous elsewhere in the state for liberally applying phrases like “the armpit of California” to just about anywhere that doesn’t feature the phrase baby greens on menus — might just have a point. There are those up in the freezing city by the bay that would be equally dismissive of all the towns up and down the Central Valley. Exactly the reason they fascinate me so.

“This is what California is,” explains geographer John Crow, “a long central valley encircled by mountains … it is a single, mountain-walled prairie.” Minus, of course, the prairie part. When some of the first whites spilled into the valley through the Sierra Nevada mountains, they described an “American Serengeti” where marshes and rivers ruled, elk roamed, and the afternoon sky could grow dark with hundreds of thousands of birds. Yet, as is the case with the eastern Sierras, the landscape of the Central Valley has been radically transformed by the manipulation of water. Rivers dammed, lakes vanished, earth buckling under years of groundwater removal, the Valley has suffered hyper-irrigation and as a result become one of the most productive farming regions in the world. The value of all the agricultural produce grown in just one year in California’s Central Valley is worth more than all the gold extracted statewide since all the mining hysteria began way back in 1848.

Yet the Valley also has more than its fair share of problems: Witness the great labor struggles and the Herculean efforts of Cesar Chavez; poverty that consistently ranks five or six of its cities in the top ten for people receiving the most public assistance; and more recently an explosion in narcotics production along the hidden dirt roads and in remote fields that by some accounts may top the state’s entire net agricultural worth. And then there’s the question of what will happen to all this agriculture once the Valley’s population triples over the next few decades, as it’s expected to do. By far the most profitable things to grow these days on Valley farms, some say, are houses.

Suffice it to say there’s more than first meets the eye in Bakersfield, as well as communities throughout the Central Valley. Don’t let a desolate downtown fool you. An evening here isn’t even scratching the surface — perhaps you’ve got to dig a little deeper than in some other places, but it may indeed be well worth the effort. After all, I’ve learned rather quickly that Bakersfield has views, southern accents, tree-lined streets, a working Woolworth’s lunch counter, ballparks brimming with curse words in at least four languages, country music the way country music is supposed to be, and — much to the delight of this particular breakfast connoisseur — Bakersfield has grits.

Learn more about the Central Valley by visiting http://www.greatvalley.org.

Thursday, 22 Jul 1999

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

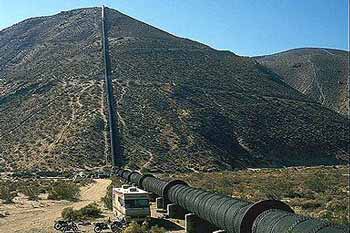

I remember being shocked when I first started flying that the borders of the states prominently featured on every U.S. map weren’t actually etched into the landscape, as so many cartographers seemed to suggest. Perhaps this should have been obvious, but it certainly threw me at the time. Yet at the southernmost edge of California is one of the few artificial boundaries, like Berlin during the cold war, that doesn’t actually defy its representation on a map. What appears as a thin straight line drawn across the landscape from above is in actual fact a series of massive metal plates rising from the ground forming a continuous fence emerging from the ocean and heading east. Not so long ago it was the difference between Alta California and Baja California. Today it’s known simply as “The Border.”

Approach it from the north and there’s no mistaking where you’re heading. “Guns Illegal in Mexico,” reads the sign as you head down Interstate 5 from San Diego. I wonder what you get heading in from the other side. I’m thinking something like “Welcome to California. May We Suggest a 9 Millimeter?”

I’m looking for an exit off I-5, a small road that will take me to a park out toward the coast that supposedly straddles the border. It’s anything but well marked, but I manage to find it and follow a road that gradually gets rougher until it turns into sand. “Welcome to the Border State Park, Hours 10-6 Thurs – Sun,” reads the sign. No sooner do I check my watch — five minutes to 6:00 — than at the far end of the dirt road in front of me appears a strange sight. At first glance it looks like a scene out of the Magnificent Seven, or perhaps the ghosts of the caballeros. As the horsemen approach, however, things veer toward the surreal, looking more like a cross between Mad Max and Blade Runner — six fatigued officers, radios and guns strapped to their waists, standing upright on their off-road ATVs, kicking up a massive cloud of dust behind them. They approach and — unable to speak through their motorcycle helmets — wave me back toward the gate. One of the more communicative ones points at his watch and shakes his head. Heeding their advice like any good citizen would, I turn back to my car only to see three helicopters, one after the other, rise out of the brush to begin their patrols. It’s nearly dusk; the long metal fence delineating north and south will soon be awash in searchlights.

To say that immigration is a hot topic in California is an understatement. We’re the home of Proposition 187, the now infamous ballot measure approved by the state’s voters in 1994 denying any publicly subsidized services to illegal aliens. This is part of the curious paradox between the state’s seemingly “liberal” image and its long history of political conservatism, particularly in the form of folks like Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon. But California is quickly changing. Demographers had predicted that by 2002 we’d be the first “majority-minority” state. Now they say, after revising their estimates, that we’re already there. I’ve also been told that the racial makeup of the people who vote isn’t at all like the makeup of the population at large; the voting contingent looks more like the population of California in the 1930s, largely white. This too is changing. One of the major fallouts from Prop 187 was that enraged Latinos have shown up at the voting booths in record numbers, and their targets — the backers of 187 — have been Republicans. As of last November’s election in California, Democrats now control the Senate, the Assembly, and the governor’s seat for the first time in decades. And by large margins. The unofficial motto of the state GOP these days is “feisty … but irrelevant.”

I often find myself in discussions about immigration and I usually wait until well into the conversation to mention that I’m an immigrant myself. Being white, sounding American, this often confuses people. “I was born in England,” I’ll say. “Lived there until I was 10.” There’s a pause. “But your parents are American?” usually comes next. No, they’re not — in fact we’ve been English for centuries, I’ll explain, it’s just that I’m good with accents. The conversation often ends with, “So really you are American,” after they do some math with my age. And then I give in. I was sworn in as a citizen two years ago, along with a roomful with Russians, Jamaicans, Liberians, Koreans, Salvadorans, Brazilians, Ukrainians, Mexicans, and Canadians. My

parents, too stubborn to take the plunge themselves, nonetheless sat in the back of the room, cheering me on with miniature American flags in hand.

All by way of proving things often aren’t what they seem. I’ve learned that I first saw this stark Southern California landscape years before I ever even came to the U.S., mistaking it for the hills of Korea on the TV sitcom MASH, a favorite on English television in the early 1970s. And now, as I head back away from The Border, I pass a tractor-trailer heading north from Mexico, packed with something else that’s from somewhere else, although you’d never know it. The shipment of palm trees exits before I do, heading out to one of the new retirement communities on the coast — a place where it’s always sunny, temperatures always in the 70s — as close as you can get to perfection, at least for now.