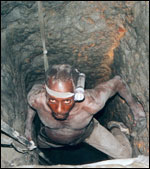

At I Trust My Legs, an illegal mining camp along a gray stream in the West African nation of Ghana, trespassers have bored vertical shafts deep into the ground. On a recent morning, Maxwell Adzoka strapped a lamp to his head, pressed his bare back and shoeless feet against the slick clay walls of one of these shafts, and climbed down, his yellow bulb disappearing into the darkness. When he reemerged, he was bearing thick stones rippled with gold, enough to buy meat, palm wine, and clothes for his eight children. It was a lucky day for Adzoka, and not only because of his find: He could just as easily have died from a collapsed tunnel, mercury poisoning, or a rifle shot.

Maxwell Adzoka descends.

Across Africa, in countries with rich mineral reserves and barren economies, thousands of the unemployed dig for fortunes on land controlled by large mining companies. Operating illegally and unregulated, these miners use primitive extraction techniques not seen in the United States since the California gold rush a century ago. With dynamite, pickaxes, mercury, and the strength of their arms, they earn a living at great threat to their health and environment.

Located on West Africa’s Gold Coast, Ghana earns the majority of its foreign exchange from gold, most of it extracted by multinational corporations. The government says these companies funnel money into public coffers and minimize environmental impacts, but disaffected villagers say the firms have ravaged their lands and given little in return. As an alternative, many locals support the illegal miners, known as galamsey, despite the threats posed by their toxic methods. Concentrated in Ghana’s heavily excavated southwestern rainforests, the galamsey comprise one of the largest groups of illegal miners on the continent.

The Gold Standard

Small-scale mining was a respected tradition in Ghana for centuries, but became a persecuted profession after the British colonized the region in the early 19th century and banned the practice. Ghana’s independent government legalized small-scale mining in 1989, but the government grants few mining concessions to peasants, forcing most people to mine illicitly.

Adzoka bristles over his lack of a legal place to dig, recalling how his ancestors mined freely. “They were working in peace, they were not having any problems,” he said, gazing toward the trenches of I Trust My Legs from his stoop below a tree. “But now, we are being harassed.”

Adzoka and other galamsey at I Trust My Legs.

Established 11 years ago, I Trust My Legs earned its name in 2000, when miners ran from a police raid. Now the 3,000 galamsey here rely on a committee that bribes the police to turn a blind eye to their illegal mining activity. Amid piles of silt and the drone of rusty water pumps, they hammer rocks in unstable tunnels that are buttressed here and there with boards. If the mining company that controls this land decides to return, another raid could force the galamsey away.

Since mining began at I Trust My Legs, Adzoka estimates that 10 workers have died here. Collapsing mine shafts during the rainy season have killed the most, but over the long run, many more could die from mercury exposure. Miners inhale mercury vapors when they heat the element in boiling pots to purify gold. Discarded into streams, mercury also builds up in the fish widely consumed by villagers. In humans, mercury exposure can cause kidney problems, arthritis, memory loss, miscarriages, and psychotic reactions.

This miner has struck gold.

Adzoka has mined with mercury for 20 years and he fears he will soon feel its effects. Nevertheless, he still handles it with his bare hands. “Even though it is dangerous and poisonous,” he said, “there is nothing I can do about it.”

At 53, Adzoka sports the well-toned arms and legs of a man in his 20s. In a country where the average life expectancy is 57, he has already outlived many in less hazardous lines of work. The only signs of his age are his receding hairline and a round belly that overhangs the band of his muddy shorts. He eats well, thanks largely to the gold he digs from the ground.

Adzoka grows palm trees, cassava, and pineapple on his two acres of land, earning an income on par with the national average of $340 a year. He and his family could survive on farming alone, he said, but the extra $150 a month he earns from mining helps pay for medicine, school supplies, and a well-rounded diet.

Chief Nana Kofi Dei II.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

A few miles down a potholed road from where I talked with Adzoka, the chief of the village of Dumasi, Nana Kofi Dei II, sat on a throne in his humbly furnished living room. He wore rings on six fingers, a bracelet, a thick arm band, an ankle band, two long necklaces with pendants, and a crown — all made of ornately cast gold. Normally, he keeps this finery locked in a closet and brings it out only for ceremonies. To sell it would dishonor the 10 generations of his ancestors who wore it and erase one of the few remaining signs that villagers in this mud-hut town once controlled the precious minerals beneath their feet.

Until a few years ago, locals still mined gold at Dumasi. The village brimmed with more than 3,000 galamsey who had fled from government clampdowns on camps elsewhere. These miners flocked to the village, lining the one paved street with impromptu houses and dotting the surrounding hills with deep shafts sunk for gold. Mercury flowed from these sites into Dumasi’s three streams — and into the villagers. A study completed by the U.N. Industrial Development Organization recently found that the majority of villagers sampled — including non-miners — carried unsafe levels of mercury in their bodies. The concentrations found in fish were up to three times higher than levels deemed safe by the U.S. EPA.

A large mining company, now owned by Canadians and known as Bogoso Gold Limited, came here in 1990 with plans to mine the hills using modern techniques — and no mercury. It seemed to Dei like a good proposition. “We thought the company would give some relief [from poverty and environmental problems],” he said, “not that it would make the situation worse.” Dei also hoped Bogoso Gold would hire villagers for well-paying mining jobs. But he soon realized the company required relatively few people to operate its heavy machinery, and wanted employees with more education than anyone living in the village had received.

Meanwhile, the thousands of galamsey who once worked here were gradually forced to leave. One of them was Adzoka. When the police raided the camp, firing their guns into the night, he fled through the forest and badly cut his face. Others fared much worse. “To escape, some people jumped into the mine pits,” he said, “and that was the end.” After the galamsey left and Bogoso Gold took over, only 2,500 villagers remained, down from a peak population of 6,000. Daily sales at Dei’s small pharmacy — once a respectable $20 — plummeted to less than $3. Farmers and other vendors also suffered. “Now children are not in school because their parents are not employed,” Dei said.

Devastation wrought by Bogoso Gold near Dumasi.

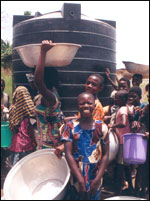

Once Bogoso Gold began mining, it bulldozed the trees and topsoil from hills, removed entire slopes, destroyed the village’s three streams, and polluted its groundwater. The company currently hauls drinking water in with tanker trucks. Until the mining ended about two years ago, it took place 24 hours a day, sometimes less than one city block from where people lived. Dei Nkrumah, a farmer, said blasting from the mine site once sent a stone sailing into the air and through the tin roof of his kitchen. “If somebody was in the house at the time the stone came through, he could have died,” Nkrumah said, staring up at the tennis ball-sized puncture. “It was dangerous.”

The General Manager for Bogoso Gold, Peter Claringbull, declined to comment for this story.

Bogoso Gold built Dumasi a school and community center and provided it with poles and cables for electricity. To some extent, the company will be required to restore the land it has mined near the village with grass and trees. Despite these improvements, Dei said he preferred life with the galamsey. “There was no disruption of our land, because we had the galamsey, but still enough land for farming,” he said. “We wish the mining companies had not come.”

In the Mine’s Eye

A short walk from I Trust My Legs, the village of Nakabah swells with the galamsey who left Dumasi. The chief there, Nana Kobinai Andoh, takes a moment to converse with other elders when asked which he prefers, galamsey or mining companies.

“The galamsey mining helps the community most because a lot of people can go and do it,” he says from his chair in a courtyard between two turquoise huts. “Formerly, burglary used to be common here,” he added, “but it is no more because people are employed [at I Trust My Legs].”

Yet the galamsey still technically commit theft, because the concession at I Trust My Legs is owned by Bogoso Gold. Andoh said he thought the company might soon return to the area, and he planned to ask it and the government to officially give part of the concession to the galamsey, as a compromise. But that is unlikely, government officials said, because mining companies refuse to give up valuable goldfields.

The creek that runs through I Trust My Legs.

Another obstacle is the location of I Trust My Legs in one of the most dangerous places imaginable for galamsey mining. The ground under the camp is laced with sulfide ores, according to Michael Sandoh Ali, district officer for the western region at the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency. When dug up and exposed to oxygen, these ores generate sulfuric acid, which further dissolves harmful heavy metals such as iron, copper, lead, and mercury, sending them into streams and groundwater. Decades ago, a company mined at I Trust My Legs, then capped the sulfides with earth and topsoil. The galamsey have reopened the wound. As the owner of this concession area, Bogoso Gold is liable for the environmental harm caused by the galamsey. “The area has been rehabilitated and it has done well,” Ali said. “But the galamsey came in and started working there. It’s unfair.”

Despite the problem, Ali said there is little he can do to solve it. “If I go and tell the police force that the devastation is too serious, that you have to get these people out of the place, then these people are given information that the police are coming,” he said. “They just don’t go to work the next day. You can never, ever track them down.” Even if he could round up the miners, Ali added, local communities wouldn’t stand for a clampdown on the galamsey. “It is part of the culture of the Ghanian.”

A Canary in a Gold Mine

The government of Ghanaian President John Kufuor announced a pragmatic plan to deal with galamsey mining last year, in which it pledged to give land to galamsey miners if they formed collective associations. According to the Wassai Association of Communities Affected by Mining, a Ghanaian environmental group that supported the plan, around 60 galamsey collectives have been formed, but the government still hasn’t followed through on its pledge.

Bogoso Gold trucks in water because wells have been poisoned.

If the government gave the galamsey legal places to mine, communities might support a crackdown on illegal exploitation, said George Awudi, mining coordinator for Friends of the Earth in Ghana. Awudi said he would prefer well-regulated, small-scale mining to strip-mining by large companies. “If proper equipment was provided for them and proper training was done, then the mercury pollution could be controlled,” he said.

Ahmed Nantoqmah, media relations manager for the Chamber of Mines, an industry group, countered that the government gives preference to large mining companies for good reason. “If you give a mining concession to the natives, they might mismanage,” he said. “If you give it to a large company, it can do it better.”

Unlike small miners, the mining companies pay 3 percent of their gross earnings to the government. Part of this money goes into a fund for environmental restoration and a portion goes to local chiefs. The remaining 80 percent funds government programs nationwide.

The signs of mining company programs were hard to miss on the road to I Trust My Legs. Hundreds of children in orange school uniforms clogged the road, going home after a day at the Prestea Goldfields School, where classes are subsidized by the mining company. Yet absent from this crowd were the seven children of Grace Ofori, who was on her way to the galamsey camp to sell boiled yams. She couldn’t afford to pay her children’s school fees, she said, but as long as she could sell to the galamsey here, she would at least be able to get by.

“It won’t be easy if they leave because I don’t have any skills,” she said, as her children hovered around her in torn T-shirts. “So it will mean I cannot feed my family.”

Before Adzoka descended his shaft again on the afternoon I spoke with him, he said the galamsey camp would remain in existence for as long as the bribing arrangement lasted with the police. But, he added, the arrangement was not to be trusted, as shown by the last raid — the one that gave the camp its name. He laughed when asked if the name still rang true for him. “Yes,” he said, “because I can run.”

Editor’s note: Locals report that Adzoka disappeared from I Trust My Legs after this story was reported. His whereabouts are unknown.

All photos by Josh Harkinson.