By Lester R. Brown

Global demand for soybeans has soared in recent decades, with China leading the race. Nearly 60 percent of all soybeans entering international trade today go to China, making it far and away the world’s largest importer.

The soybean was domesticated some 3,000 years ago by farmers in eastern China. But it wasn’t until well after World War II that the crop gained agricultural prominence, enabling it to join wheat, rice, and corn as one of the world’s four leading crops.

This rise in the demand for soybeans reflected the discovery by animal nutritionists that combining 1 part soybean meal with 4 parts grain, usually corn, in feed rations would sharply boost the efficiency with which livestock and poultry converted grain into animal protein. As China’s appetite for meat, milk, and eggs has soared, so too has its use of soybean meal. And since nearly half the world’s pigs are in China, the lion’s share of soy use is in pig feed. Its fast-growing poultry industry is also dependent on soybean meal. In addition, China now uses large quantities of soy in feed for farmed fish.

Four numbers tell the story of the explosive growth of soybean consumption in China. In 1995, China was producing 14 million tons of soybeans and it was consuming 14 million tons. In 2011, it was still producing 14 million tons of soybeans—but it was consuming 70 million tons, meaning that 56 million tons had to be imported.

China’s neglect of soybean production reflects a political decision made in Beijing in 1995 to focus on being self-sufficient in grain. For the Chinese people, many of them survivors of the Great Famine of 1959–61, this was paramount. They did not want to be dependent on the outside world for their food staples. By strongly supporting grain production with generous subsidies and essentially ignoring soybean production, China increased its grain harvest rapidly while its soybean harvest languished.

Hypothetically, if China had chosen to produce all of the 70 million tons of soybeans it consumed in 2011, it would have had to shift one third of its grainland to soybeans, forcing it to import 160 million tons of grain—more than a third of its total grain consumption. As more and more of China’s 1.35 billion people move up the food chain, its soybean imports will almost certainly continue to climb.

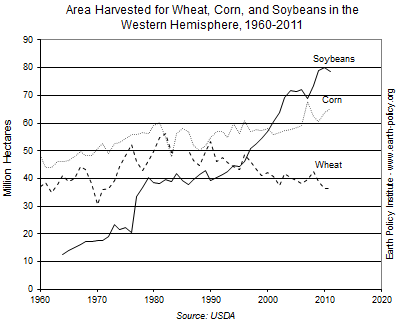

The principal effect of skyrocketing world soybean consumption has been a restructuring of agriculture in the western hemisphere. In the United States there is now more land in soybeans than in wheat. In Brazil, the area in soybeans exceeds that of all grains combined. Argentina’s soybean area is now close to double that of all grains combined, putting the country dangerously close to becoming a soybean monoculture. Together they account for over four fifths of world soybean production. For six decades, the United States was both the leading producer and exporter of soybeans, but in 2011 Brazil’s exports narrowly eclipsed those from the United States.

Although most of the growth in the world grain harvest since the mid-twentieth century is from the tripling of grain yield per acre, the 16-fold increase in the global soybean harvest has come overwhelmingly from expanding the cultivated area. While the area expanded nearly sevenfold, the yield scarcely doubled. The world gets more soybeans primarily by planting more soybeans. Therein lies the problem.

The question then becomes, Where will the soybeans be planted? The United States is now using all of its available cropland and has no additional land that can be planted to soybeans. The only way to expand soybean acreage is by shifting land from other crops, such as corn or wheat. In Brazil, new land for soybean production comes from the Amazon Basin or the cerrado, the savannah-like region to the south.

Put simply, saving the Amazon rainforest now depends on curbing the growth in demand for soybeans by stabilizing population worldwide as soon as possible. And for the world’s more affluent people, it means eating less meat and thus slowing the growth in demand for soybeans. Against this backdrop, the recent downturn in U.S. meat consumption is welcome news.

For further reading on the global food situation, see Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity, by Lester R. Brown (W.W. Norton: October 2012). Supporting data sets and PowerPoint presentations are online at www.earth-policy.org/books/fpep.