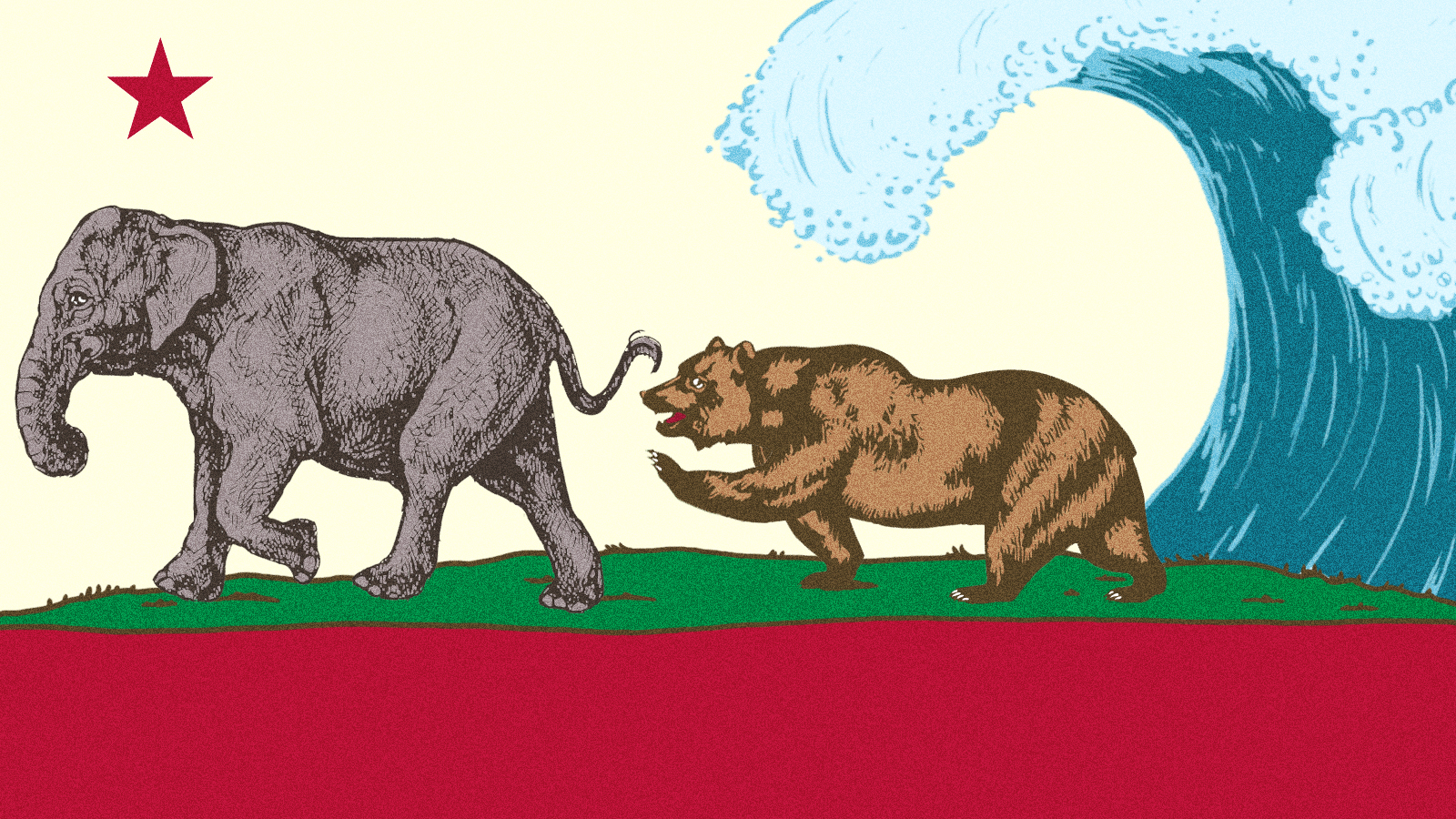

For the past decade, Democrats hoping to pass a big climate law have played Charlie Brown to the Republicans’ Lucy. Despite the GOP making it clear it has no intention of holding the ball for a global warming kick, the left routinely convinces itself that their counterparts will kneel into position once it gets a running start.

In 2010, Senate Democrats appealed to Republicans to pass federal climate legislation, only to see almost every conservative bail on them. Since then we’ve seen the old pattern repeat in statehouses and ballot boxes around the country: Democrats ask the GOP to hold the ball then go flying head-over-heels.

But then in July, a cadre of eight California Republicans crossed the aisle to vote with Democrats and pass that state’s cap-and-trade law.

The partisan space-time continuum shuddered — and this was before back-to-back superstorms, Harvey and Irma, buffeted the United States. Had the well-worn GOP force field stymieing progress on climate change begun to crack at the far-western edge?

While an enraged right planned the ouster of its leader, Chad Mayes, California Governor Jerry Brown praised him and the others who’d broken ranks. As did former Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who wrote: “I hope Republicans around the country can learn from the example.”

In statehouse testimony, speeches that would typically build to Republicans stridently aligning against carbon pricing went off script. “First thing I want to make clear, I personally think cap and trade sucks,” California Assemblyman Devon Mathis said at the beginning of a short speech. As he spoke, he came close to tears while urging his compatriots to vote “yes” for the program he’d just disparaged. So what the heck was happening there?

Dan Kahan, a professor at Yale who studies the way tribal identity affects how people think, has long argued that Republicans will become more willing to engage on climate change as constituents begin asking them to bring home money to adapt to a warming world. “The sooner the issue becomes one about dollars and cents for the districts,” he says, “the more quickly the logjam we have now will break loose.”

For years, journalists and activists have said that wholesale Republican opposition to climate action can’t last forever. Now, with millions of Americans soaked in floodwaters from never-before-seen storms, that ideological logjam shows signs of breaking up. Case in point, the ol’ maverick John McCain: The one-time cap-and-trade supporter is suddenly, once again, looking for “common sense solutions” to climate change. And the Trump administration might even be flip-flopping on its decision to pull out of the Paris Agreement. (Though we advise against holding your breath.)

Moving forward, there are three primary paths for Republicans to choose from as they debate climate legislation — three paths that three California GOP legislators traveled as they mulled cap and trade. The paths each legislator picks, combined with the reaction of their constituents, will determine how quickly the nation will react to a climate change-effected future that appears to already be here.

GOP option 1: Dig in

So far, most Republicans have bet that the political costs they will pay for engaging on climate policy are worse than the costs their constituents will pay as a result of climate change. This could shift, as Kahan suggests, if the damages from coastal erosion, drought, and flooding begin to spiral over the next decade or so. And any more Harveys, the bill from which is estimated at just under $200 billion to the U.S. economy, should hasten that move.

But for now, GOP politicians are still calling climate action prohibitively expensive. That’s the reason California Assemblymember Melissa Melendez gave for opposing cap and trade, asserting that her constituents didn’t feel climate change was imminent. “While they care about the environment and they want to protect Mother Earth, they do not feel,” she explained, “that Southern California will burst into flames if we don’t pass this bill.”

Texas Congressman Lamar Smith, head of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, went a step further. He went on what Buzzfeed called a “secret tour of the melting Arctic.” When he got back, he wrote that rising greenhouse gas levels were “indisputable.” Then he added, “The benefits of a changing climate are often ignored and under-researched.”

But the classic Republican gambit is to simply ignore the issue. And some politicians go to absurd lengths to avoid addressing the environmental elephant in the room. That seems to be Florida Governor Rick Scott’s preferred move. He has censored the phrases “climate change” and “global warming” in state agencies, forcing public servants into comical verbal gymnastics during legislative hearings. Even after Hurricane Irma ravaged his state, including compromising infrastructure and flooding parts of 22 counties with sewage, Scott saw no reason to change course.

“Clearly our environment changes all the time, and whether that’s cycles we’re going through or whether that’s man-made, I wouldn’t be able to tell you which one it is,” Scott said last week, according to a Politico report.

The reinforcement of head-in-the-sand views for Republicans who want to hold the line comes from the top. The Trump administration is starting to employ Scott-style tactics in directives issued by its Cabinet departments.

GOP option 2: Strike a deal

Bargaining seems like an obvious choice for Republicans. By making a deal on the California bill, Republicans came away with spoils: They got $260 million a year in tax cuts for business and agriculture. They got another tax — a landowner fee to fund wildfire prevention — eliminated completely. And they got a market-based, industry-friendly version of cap and trade that the Chamber of Commerce and agricultural interests supported.

What did Republicans give in return? Not much. The Democratic majority in the State Assembly had already passed a law that committed the state to squeezing carbon out of its economy. As Devon Mathis said, this bill was an “opportunity to make something many of us think is horrible a little bit better.” By helping it to pass with the two-thirds majority that Governor Brown wanted, Republicans helped protect the legislation from legal challenges — including from groups that would want it to be more harsh on fossil fuel companies.

But there’s a reason Republicans, despite being the party of Trump, don’t like deal-making: It’s dangerous. The California GOP immediately booted Chad Mayes from his perch as the party’s Assembly leader for working with Brown. Mayes’ fate recalls what happened to South Carolina Congressman Bob Inglis when he voted for climate legislation in 2012: He lost his seat to a primary challenger.

For his constituents, Inglis talking about climate change was like dressing in the opposing team’s jersey. “I think his constituents saw that as a sign that he really didn’t share their values,” Kahan says.

That same feeling of betrayal coursed through an agricultural exhibition center where Mathis held a town hall meeting. “You are supposed to stand up for those who voted for you,” said one speaker, the Valley Voice reported. Another told Mathis he’d “stamped a ‘D’” at the end of his name.

Mathis defended himself by pointing out that pure tribal loyalty isn’t politically effective: “If you want to rebuild the Republican Party, then you need to be more than the party of ‘no,’” he told his constituents. By being at the table, he reminded them, the GOP was able to move cap and trade to the right.

Still, almost every idea dreamed up for climate change mitigation requires some centralized regulation and introduces new spending — issues conservatives tend to see in black-and-white absolutes. “For Republicans to say, ‘We voted for this because it could be worse,’ is like saying, ‘It’s better to drown in 10 feet of water than 20 feet of water,’” former California Republican Assemblyman Dan Logue tells me.

GOP option 3: Embrace change

Rocky Chávez is a bull-necked marine colonel who, though he’s a Republican, feels no need to toe the party line on climate change. The GOP can’t go on protecting people from the truth for the sake of cohesion, he told me.

“It’s like Elvis — Elvis is not alive anymore, people, I got news for you,” he says, equating his party’s collective climate denial to the outlandish headlines seen on National Enquirer covers. “We did go to the moon, those aren’t fake pictures taken out in the Arizona desert. There is no Sasquatch; he’s not running around in the forests of California.”

Chávez has previously come under fire for his liberal positions on gay marriage and immigration. But all the sound and fury has cost him little, politically. After all, he represents a coastal district near San Diego that narrowly favored Clinton in 2016.

“People are going to say, ‘Oh, he’s that idiot who doesn’t hate gays, doesn’t hate immigrants, and actually wants to protect the environment,’” Chávez says. “You know what? I’m OK.”

There are other California Republicans, he adds, who want to take a more proactive position on climate change. But they are scared to stick their necks out on issues like cap and trade. “I can tell you that it was much more than the seven who voted for it who believed in it,” Chávez tells me.

Tom Del Beccaro, former chair of the California Republicans, says it doesn’t make sense for most GOP politicians to follow Chávez’s example. “A party does not gain any voters by adopting the position of the opposition,” he explains. “There’s no reason for a Democrat voter to vote for a Democrat-light.”

Because Republicans haven’t defined their own path on climate change, they can’t use the issue to hold onto districts like Chávez’s when incumbents bow out. Case in point, U.S. Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen from South Florida, who has advocated for a climate-mitigation strategy. She isn’t running for reelection in 2018, and a Democrat is poised to take over her seat.

Similarly, when California first passed its climate change law in 2006, just one Republican voted for it: Shirley Horton, a politician from a relatively liberal district that flipped to blue as soon as she termed out of office.

So you can see Beccaro’s point. Republicans have to provide voters a clear choice, he says: “They have to pick some issue where things are breaking down, where the majority party isn’t providing a solution, and offer a plausible alternative.”

Climate change could actually be such an issue, Beccaro says. Republicans could, for instance, convince voters that they could combat it more affordably. It’s a sentiment echoed by Bob Inglis, who believes conservatives have the best tools needed to address climate change. Republican constituents, he explains, just need to hear their leaders discuss climate policy in a language they understand and respond to.

“What we deeply believe as conservatives is that free enterprise is far more creative than government mandates — and if you simply level the playing field by eliminating all the subsidies for all the fuels, then the free enterprise system can deliver the solutions,” he says. “That includes the biggest subsidy of them all, which is being able to belch and burn into the trash dump of the sky without accountability for the health and climate damages you are causing.”

According to Inglis, Republicans would be foolish if they wait to act until sentiments on climate change shift. “Leadership is defined as helping to see what is coming,” he says. “Sure you risk your seat by leading, but isn’t that what it’s all about?”

His former colleagues may already be taking his advice. Politicians like Florida Congressman Carlos Curbelo — a Grist 50 member — are starting to address climate change by introducing bills to protect against floods and voting to ensure the Defense Department keeps adapting to a warming world. Curbelo, who last week connected Irma and Harvey to climate change, is part of a new bipartisan climate caucus in Washington with 28 Republican members.

#Climate Caucus' @RepCurbelo on #Irma: "Climate change without question contributes to strength and factors that lead to these events." pic.twitter.com/gyCQEJoMiO

— Citizens' Climate Lobby (@citizensclimate) September 13, 2017

And in California, though Mayes was ousted from his leadership position, his replacement praised him for the cap-and-trade negotiations. San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, probably the most popular Republican in the state, recently said it was time for his party “to stop ignoring climate change.”

These are perhaps the first signs of evolution. As Politico writer David Siders put it recently, “If the Republican Party is undergoing a shift on climate, it is at its earliest, most incremental stage.” The California GOP may be furthest into that transformation thanks to plummeting Republican registration in the increasingly diverse state.

“Today just 26 percent of California voters are registered Republicans,” reports Laurel Rosenhall at CALmatters. And “7 percent of state Republicans are considering abandoning the party because of its stance on climate change.”

California conservative voters could decide how far the GOP will tack nationally, in part by either rewarding the bargainers and change agents for bringing home the bacon or throwing them out of office for breaking ranks.

Eight Republicans isn’t a big number. But it’s a fifth of the GOP caucus in the California state legislature. In the past, climate bills might pick up one or two maverick conservatives — one or two drops of water seeping through an imperceptible crack in the dam. This time it was the Republican leader of the Assembly, plus seven others. The drops have become a trickle.