Xavier Becerra, California’s combative attorney general, has become the Golden State’s face of resistance to the Trump administration’s domestic initiatives, the blunt voice rejecting the president’s attempts to roll back the progressive immigration and environmental policies so central to California’s sense of itself.

At a June 16 press conference, for example, Becerra pushed back against stricter immigration enforcement, saying his office would review conditions at immigrant detention facilities in conjunction with a legislative measure that prohibits local governments from renting out jail beds to U.S. Immigration and Customs. One week earlier, Becerra sent Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke a withering, 11-page letter that flat-out rejected the president’s executive order aimed at delisting or shrinking national monuments his predecessors had established in California.

Yet as eloquent and forceful as the attorney general may be in his defiance, there are limits to the state’s protective stance. Becerra is mounting what amounts to a rearguard action because he has little choice in this age of Trump the Tumultuous.

Viewed from my perspective as an environmental historian, this defensive rhetoric runs counter to the no-holds-barred approach that defined California’s post-World War II drive for economic growth and social justice.

It is as if, for the time being, the California Dream so critical to Becerra’s personal success — and many others’ — has been put on hold.

Challenging Trump

The hardworking son of immigrants and the first in his family to go to college, Becerra finished law school in 1984, was elected to the state assembly, and then served in the state’s Department of Justice before winning an impressive 12 terms to the U.S. House of Representatives.

At each stop along the way, he has been a staunch advocate for the poor and marginalized, those who need a hand up and out. In January 2017, Gov. Jerry Brown (who is playing a similar role as Becerra on an international stage) tapped the politically savvy Becerra to replace newly elected Senator Kamala Harris as AG to become the first Latino to hold this high office in California.

Becerra’s tough-minded approach to his latest job has made him ubiquitous this commencement season. Between May 15 and 23 alone, he addressed the political science graduates at the University of California, Berkeley, those receiving their law degrees at USC and the University of San Francisco, and bachelor’s-earning undergrads at Occidental College.

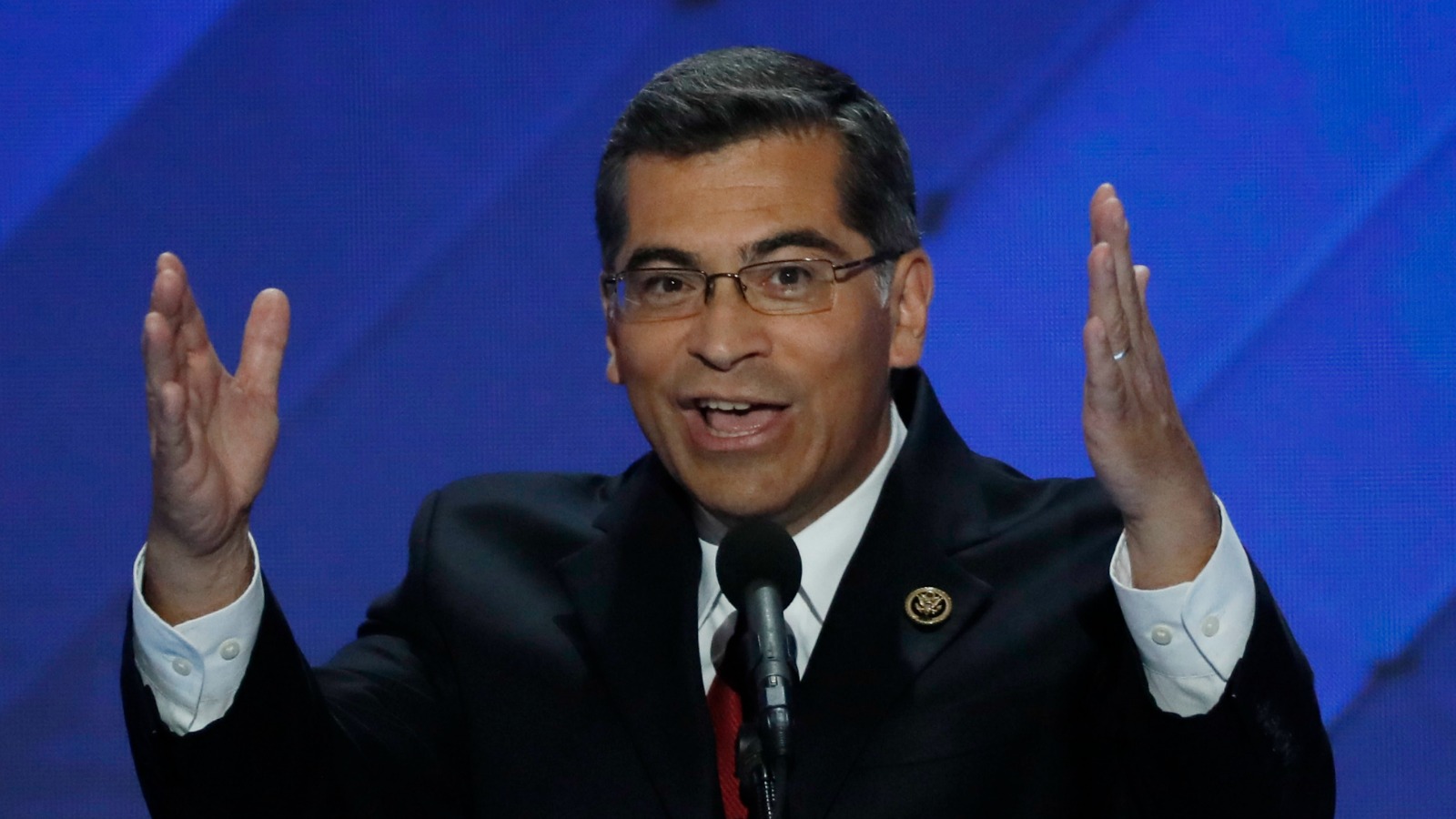

Xavier Becerra has taken a defiant — and, by necessity, a defensive — tone vis a vis Washington. REUTERS/Mike Segar

Even as he cheered these graduates’ academic successes, he reminded them of the rough-and-tumble political environment they were entering. Becerra spoke of how he and other state AGs were challenging the legality of Trump’s Muslim travel ban. He affirmed his deeply felt support for the undocumented and asserted that cities could proclaim themselves sanctuaries, free from executive branch interference.

In resisting the Trump administration’s review of national monuments, Becerra wrote what amounts to a legal brief that cited judicial rulings and legislative records and made a strong case for a kind of states-rights environmentalism. Arguing separately against a plan to open up offshore drilling, he said: “Instead of taking us backwards, the federal government should work with us to advance the clean energy economy that’s creating jobs, providing energy, and preserving California’s natural beauty.”

California’s cultural clout

The late, great Kevin Starr argued in his magisterial, multi-volume study of California that the state’s particular genius is in offering “the highest possible life for the middle classes.” It proved time and again to be “the best place in the nation to seek and attain a better life.”

Fueled by a generous stream of tax dollars, the state’s educational systems, from K-12 through college and university, were the envy of the world. So, too, were its high-speed highways and highly engineered water systems, as well as its agricultural productivity, artistic energy, and technological creativity. California was a state on the move.

Its benefits were also broadly accessible: beaches were public, parks and open spaces plentiful, higher education was cheap. Here, democracy flourished, or at least it could do so. Where it did not, people battled to ensure that it would.

Those toiling in the fields of the Central and Imperial valleys, for example, endured oppressive conditions, but gained an important measure of control over their lives and livelihoods through the formation of the United Farm Workers of America. The struggles that African-Americans and Asian-Americans, Latinos, women, and LGBT activists have waged for increased rights, solidarity, and opportunities did not always originate in California, but they gained political visibility and cultural clout when manifest on the coast. If you wanted to remake yourself, go West.

Setting pace on public health

But all that prosperity took its toll. Clearing the air of the state’s legendary pollution — “don’t breathe too deeply when you arrive in California” used to be the warning — has taken decades. Grassroots activists, dedicated educators and scientists, and some principled public officials fought against entrenched opposition in Sacramento, Detroit, and Washington, D.C., to secure what now are the nation’s toughest environmental controls. More needs to be done, but these regulations have had a profound impact.

It is not by happenstance that the EPA owes its existence to a Californian (President Richard Nixon signed it into law December 1970). Or that the Clean Air Act grants the state the right to institute stricter measures than the federal government (which is why the current administration tried to deny California’s right to set higher standards).

The ground-level consequences of such innovations as catalytic converters is evident in enhanced public health. When I was a student at Pitzer College in Claremont in the 1970s, I almost never glimpsed the smog-enshrouded Mt. Baldy (elevation 10,050 feet), a few miles away. Today, its towering presence is visible 24/7.

There was no way to predict this remarkable turnaround when my classmates and I gathered outdoors for our graduation in 1975. And no way would bluer skies have become commonplace had the state heeded the advice our commencement speaker imparted to those entering a depressed job market in a society constrained by the budget-busting Vietnam War and post-Watergate cynicism. Hunker down, he said, hunker down.

That 1975 recommendation from a California assemblyman to retreat from the world was as wrong then as it is now in our similarly fraught environment. Rather than simply throw up a wall to fend off the barbarians at the gates, however understandable, California needs to reassert the bold, expansive, and democratic vision that has made it California. A prospect that requires a shared and tenacious commitment to the commonweal.

And a sense of agency. “You don’t have to do it by yourself,” Xavier Becerra told Berkeley seniors. “You don’t have to have done it before. But when you get out there with the guts and the grit and the ganas [desire], you can make a difference.”

That’s how dreams become real.

![]()