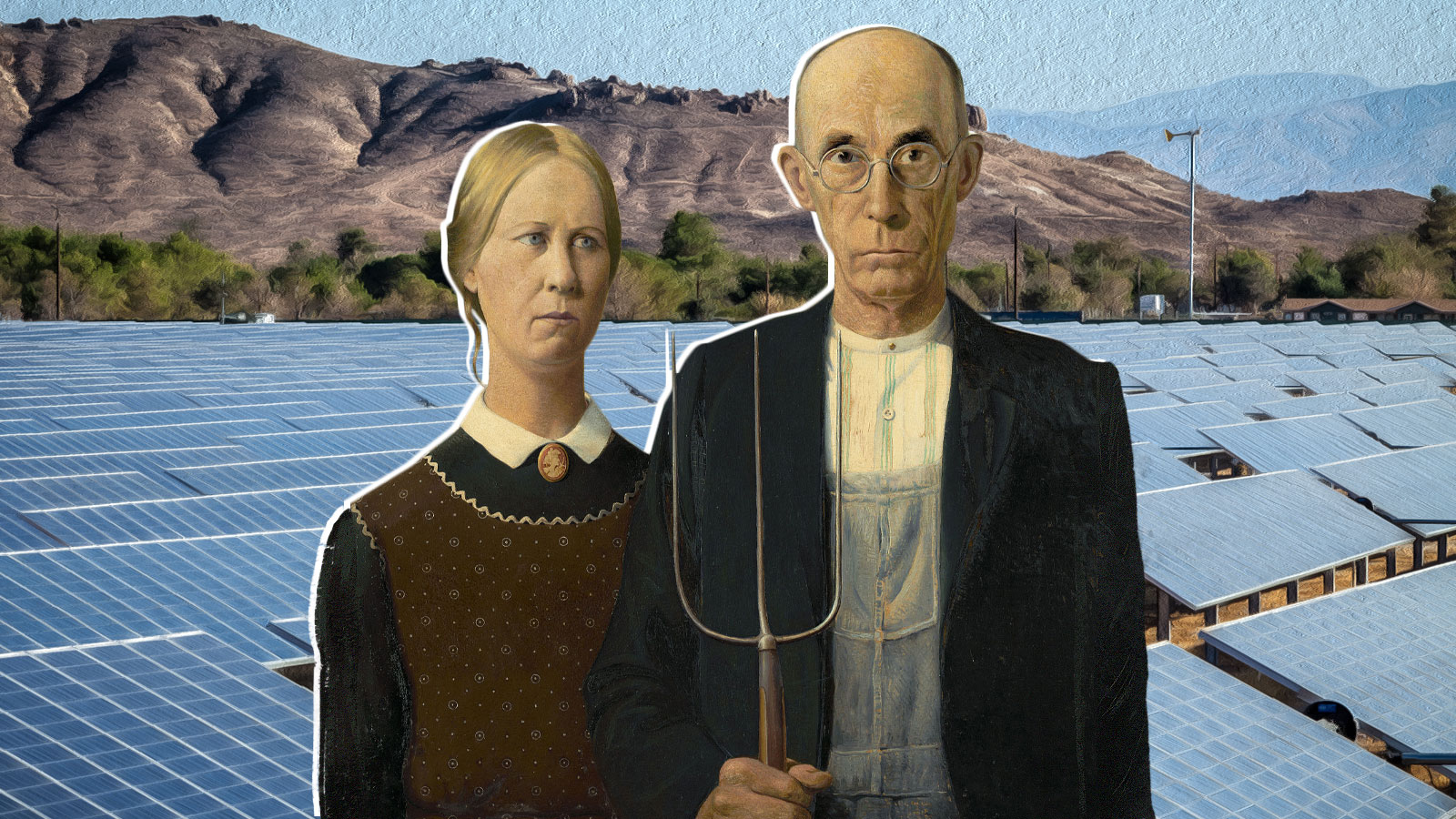

If California is to meet its goal of running on 100-percent clean electricity by 2045, fields that once grew hay are going to have to start producing electrons. That’s according to a new report from The Nature Conservancy that estimates the state will need to cover an area at least twice as large as Yosemite National Park with solar panels and wind turbines.

That may seem like an ambitious ask, but the amount of California land devoted to renewable energy is already slated to grow exponentially. Part of the driving force is water scarcity: A state law now requires water regulators to figure out how to balance their accounts so that groundwater levels stop dropping. (For the past 50 years California has been pumping far more water out of the ground than filters back into aquifers.) To comply, farmers would have to stop irrigating at least half a million acres, according to a study by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California.

Letting valuable land go unirrigated isn’t exactly appealing to many growers. But the Nature Conservancy report suggests a good chunk of that acreage could be used for solar and wind farms. The report states that between one-third and one-half of the space needed by the state for renewables could come from agricultural acres starved for water.

California farmers have already begun embracing solar panels. For some grow operations, installing a small number of solar panels has been a way to save on energy bills. A few years ago the Bowles Farming Company, near Los Banos, California, put up solar panels on four acres to partially offset the electricity needed for a new drip-irrigation system. “When we converted to drip we started to see increased costs because we’d gone from gravity-driven irrigation to pump-powered irrigation,” said Derek Azevedo, the executive vice president of Bowles. Azevedo said the investment is paying off, and the company is planning on erecting more panels.

Other farmers are converting much bigger sections of their land to solar farms. The Los Angeles Times recently listed a few of the major projects underway: There are plans to build the largest solar farm on earth on agricultural land, in California’s Central Valley. Maricopa Orchards, at the southern end of the Central Valley, is putting up 4,000 acres of solar panels, and setting aside 2,000 acres of habitat for kit foxes and burrowing owls, as environmental mitigation.

But for all the energy sense it makes to plant solar panels in sun-soaked agricultural areas, the Nature Conservancy notes that there may be pushback when it comes to the impact on native flora and fauna. Unless new solar operations are placed carefully, those miles of panels could destroy important habitat for wildlife, and cover some of the most bountiful farmland in the world.

Another potential roadblock: Although planting solar panels where almond trees once bloomed could help defuse California’s looming water crisis, so far, most installations have gone up on cattle pasture and other types of land that offers low profits per acre, said Ellen Hanak, who directs the Water Center at the Public Policy Institute of California. “A lot of it is going on non-irrigated rangeland,” Hanak said.

But if farmers also have to stop growing on irrigated land to avoid overdrawing aquifers, solar panels would make sense on about 9 percent of this idled land, according to the Public Policy Institute of California’s estimates.

That’s not stopping several California ag bigwigs from jumping on the solar bandwagon. Lynda and Stewart Resnick, who control more farmland than anyone else in America, are building solar panels on the massive pomegranate, citrus, and nut plantations of their Wonderful Company, north of Bakersfield. The company should be able to make as much money selling solar power as it does selling almonds and pistachios within the next few decades, Steven Swartz, the company’s vice president of strategy, told the L.A. Times.

And a 20,000-acre solar farm — the largest in the world — is planned on the west side of the Central Valley, on land tainted with crop-choking salts, according to the same report in the L.A. Times.

And what about the rest of the acreage needed to meet California’s clean energy goals? The Nature Conservancy’s analysis suggests that if it builds major transmission lines to other states, California could meet its energy needs without spilling into important wildlife habitat.