The drive to Casey and Amber O’Neill’s HappyDay Farms winds up a dirt track off Highway 101, three hours north of San Francisco. The road climbs to 3,000 feet along a ridge with stunning views of pine-covered mountains and the blue band of the Pacific Ocean, 25 miles to the west.

As I turn down the O’Neill’s pitched driveway, a barking Great Dane–Catahoula named Emma rushes me, hackles raised. Casey and Amber insist she’s friendly, but it be would difficult to approach the O’Neill homestead undetected. And that’s by design.

The O’Neills grow cannabis in northwestern California’s infamous Emerald Triangle, a densely forested region of labyrinthine back roads, secret valleys, and perennial creeks. For more than 40 years, it’s been a great place to hide out and grow a prohibited but highly desired product — not just for the O’Neills, but for scores of other off-the-books growers, many of whom have been farming here for generations.

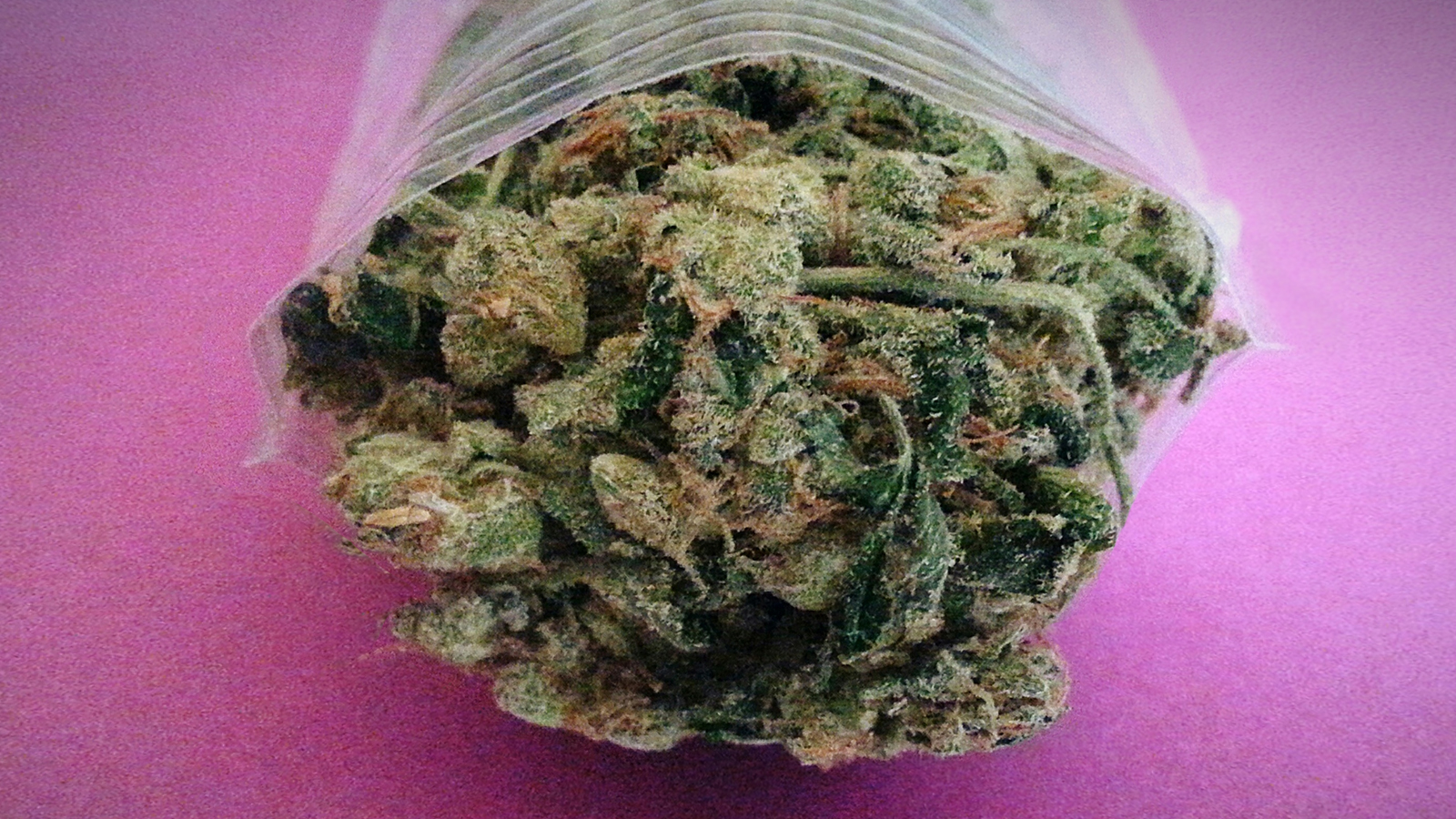

Casey O’Neill was born 35 years ago on this hilly, 20-acre spread. One acre of his property is flat enough to produce vegetables and strawberries, which he sells to nearby restaurants and members of a CSA. But it’s the rows of cannabis that bring in most of his income. His brother and father grow the same lucrative product on adjacent properties: a well-known hybrid strain called The Great Success, which took 11th place out of more than 650 entries at last year’s Emerald Cup, the state’s premier pot competition.

Grist / Google Earth

The Emerald Triangle is the Napa Valley of cannabis. Blanketing more than 10,000 square miles in Trinity, Humboldt, and Mendocino Counties, the region produces about 60 percent of the nation’s pot, most of which heads out of state on the black market.

And just as winegrowing and tourism dominate Napa County’s economy, so does cannabis dominate here, helping to fill the void created by the collapse of the once-robust fishing and timber industries. In Humboldt County, the region’s heart, researchers estimate that cannabis provides a third of private-industry revenue; in the triangle at large, the California Growers Association, a cannabis trade group, says every dollar spent on the cannabis industry leads to at least two dollars spent elsewhere.

But change is coming, thanks to voters’ passage last year of Prop 64. Starting in 2018, Californians will be able to legally grow and possess recreational cannabis. That’s in addition to medical weed, which the state legalized in 1996.

From an environmental standpoint, ending prohibition should be a boon. Illegal cultivation creates a raft of environmental problems — erosion, clear-cutting, garbage dumping, poisoned watersheds, and water diversions from creeks that support imperiled salmon and steelhead trout. The state will also begin collecting fees and taxes from growers who go legit; about $1 billion is expected next year, of which 20 percent will go toward watershed protection and remediation of state lands that were damaged by growers.

But for the O’Neills and other small-scale growers in the Emerald Triangle, legalization looks a lot less appealing. Many are either unable or unwilling to pay state or county fees, and even for those who can, legalization will increase competition from large-scale, cut-rate growers.

Fred Krissman, a Humboldt State University anthropologist conducting field studies of cannabis growers in the region, predicts “massive increases in unemployment, poverty, child hunger — a disaster.” The transformation might also offer a cautionary tale to other states embarking down the path of legalization.

In 2016, California’s legal medical cannabis industry — which fills the shelves of regulated dispensaries throughout the state — generated $1.8 billion in revenue. Meanwhile, the illicit markets pulled in $5.1 billion, according to the Arcview Group, a cannabis investment and research firm in Oakland.

Once legal recreational cannabis hits the market, Arcview forecasts its value will hit $5.8 billion in the next four years.

But how much of that pot will come from the Emerald Triangle? So far, only about 3,000 of the region’s operators, out of roughly 50,000 farms or “grows,” have applied for permits and licenses, but that number is growing as more growers come forward. For some operators, the cost of legalization – tens of thousands of dollars for even a modest-size operation, not including attorney and consultant fees — is simply too high.

Compounding the financial hit is competition from the south, where well-capitalized operators are planting cannabis in giant Salinas and Central Valley greenhouses and urban industrial parks. Economies of scale, plus easy access to labor and highways near lucrative markets, lower those operators’ price point to about $1,300 a pound. Just a few years ago, Emerald Triangle growers could get more than triple that.

As if that weren’t bad enough, the Emerald Triangle’s growers who have chosen to go legit, including the O’Neills, face further competition close to home. With lower overhead and no sales tax or permit fees, growers who choose to stay illegal can easily undercut legal operators’ prices.

As the industry emerges from the underground economy and blinks in the bright light of regulation, no one is quite sure what success will look like. The cannabis industry has existed outside the law for decades, but also well outside of mainstream agriculture. That has allowed small-scale growers to maintain financially and environmentally sound family-owned plots — a rarity in the rest of the ag industry, which has grown dependent on chemical companies and squeezed by low crop prices.

Casey and Amber O’Neill stand on a hillside at HappyDay Farms. Stett Holbrook

“We’ve seen how 20th century agriculture can be really bad for community, and really hard on the land, hard on workers and families,” Casey O’Neill says. “If we don’t build a different 21st century agriculture, we’re fucked.”

Done right, he adds, cannabis legalization offers a way to keep small, diversified pot-and-produce farms like his afloat. “It’s much bigger than growing some weed. We’re trying to put a face on small farms and communicate what we do, and why it’s valuable to society.”

When I first met Humboldt State’s Fred Krissman at a California Bureau of Medical Cannabis Regulation meeting in Santa Rosa last year, I thought he was a grower. He looked the part, sitting in the back of the room wearing a beanie pulled low and a cannabis farm T-shirt.

As an anthropologist studying cannabis growers, he cultivates the look to better mix with his research subjects, with whom he lives for days at a time.

Krissman works at Humboldt’s five-year-old Institute for Interdisciplinary Marijuana Research, the first academic research group to focus on cannabis — the role it plays in the regional economy and its impacts on community relations, the environment, and human health.

He hopes a majority of cannabis farmers can find the environmental and economic balance that Casey O’Neill exemplifies, but as an academic, Krissman is skeptical.

The industry’s shift into the legal sphere, he says, may pressure all cannabis growers — legal and illegal — to operate more like modern agriculture, with its “get big or get out” ethos of debt, larger investments in equipment, labor and facilities, and offsite corporate ownership.

In 2014, after Colorado legalized recreational and medical cannabis, prices plummeted as scores of new growers flooded the market, many of them large-scale operations that hold licenses for cultivation, distribution, sales, and other business activities.

According to Cannabase, a Colorado-based online retail site, the wholesale price for a pound of recreational pot dropped 38 percent in 2016, while medical marijuana fell by 24 percent. A similar phenomenon is happening in Washington State, which legalized recreational cannabis in 2012.

As an example of how industrial pot could affect California growers, Krissman points to Harborside, an Oakland-based cannabis dispensary that’s developing a 47-acre farm with 360,000 square feet of greenhouses in the Salinas Valley. Jeff Brothers, that company’s chief executive officer, told a reporter this past April: “If we want cannabis to be widely accepted, we need it to be cheap.”

That’s an imperative with which Krissman vehemently disagrees.

“If we force the cannabis industry into the capitalist mode of agribusiness,” he says, “this is the logical transition that’s going to occur — the one that our politicians and many people say they don’t want.”

To help protect Northern California’s traditional growers, Krissman suggests limiting farms to one acre, as well as imposing a government-subsidized floor price of $1,000 per pound at the farm gate — a proposal he realizes has little chance of passing muster in the current regulatory climate.

The growing glut of cannabis is already pushing prices to that floor, with no sign it will hold. But if public policy makers really do want rural communities to thrive, Krissman says, then they have to enact laws protecting them.

State lawmakers have created a tiered-fee structure, based on the number of plants and size of operation, to help cottage-scale growers survive in the post-legalization landscape. But even that, many say, isn’t enough to help Emerald Triangle growers match the economies of scale enjoyed by larger operations to the south.

Susan and Paul, partners in a small medical cannabis company called Lovingly and Legally Grown, are among those who fear the legalization juggernaut. They asked that their last names not be used because of ongoing raids in their region by authorities, even on legal growers.

They belie the cliché that all pot growers are raking in the money. Last year, they grossed $35,000, producing and distributing a line of tinctures, oils, and balms, working with doctors to create custom blends of cannabinoid (CBD) — a non-psychoactive compound that treats anxiety, epilepsy, arthritis, and other ailments.

Under the new regulatory framework, they estimate their annual fees and permits will top $30,000 next year.

“This is what is presenting us with this terrible quandary right now,” says Susan over a table filled with her homemade cheese, almonds, and gluten-free crackers. “We don’t know if we can continue.”

She and Paul now travel the state, attending hearings on cannabis regulation and explaining how legalization threatens to annihilate those who choose to stay small.

“Everybody wants to get their beak wet,” Paul adds. “All they know is this is a billion-dollar industry, and they want their piece of the pie.”

Indeed, 250 miles south of the Emerald Triangle, in California’s Salinas Valley, a 21st century cannabis industry is rising amid the region’s traditional crops of lettuce, strawberries, artichokes, broccoli, and wine grapes.

To protect Salinas Valley’s existing $5 billion agricultural industry, Monterey County officials have restricted cannabis cultivation to existing greenhouses, a land-use decision that has kicked off a real estate frenzy for tumbledown buildings that used to grow cut flowers until NAFTA opened the door to cheaper Colombian imports in the 1990s.

“Greenhouses are the most efficient way to grow,” says Omar Bitar, co-founder of Grupo Flor, a Salinas-based cannabis business consortium. “We have the ag infrastructure and, most importantly, we have the labor pool.”

Today, Grupo Flor leases or owns about 2.6 million square feet of greenhouse and indoor growing space in Monterey County. Eight-foot-tall chain-link fences, topped with razor wire, encircle the properties, which are dotted with security cameras and large “no trespassing” signs.

Inside the greenhouses, computer programs manipulate light exposure, spurring plants to flower early and produce multiple crops a year, instead of the single crop that outdoor growers, reliant on the sun, raise.

At Grupo Flor’s Salinas office, a whiteboard lists revenue projections for each of the company’s five business ventures: real estate, cultivation, manufacturing, investment, and retail. This year, the company will gross $5 million from its leases, says Gavin Kogan, a Grupo Flor cofounder. Next year, if all goes well, he projects gross earnings, from all Grupo Flor ventures, of $30 million and more than $80 million in 2019.

A former cannabis business attorney who favors checkered Van’s skateboard shoes, Kogan claims not to be motivated by riches. Instead, he touts the ability of cannabis to create economic opportunity for the majority-Latino population in an area riven by crime and lack of economic opportunity. Salinas has the highest youth homicide rate in the state and a total gun murder rate more than seven times the national average.

“The goal is to make the Salinas Valley the central plumbing for the California cannabis industry and generate jobs and completely reconstitute the economic infrastructure of this valley,” Kogan says.

And what of the Emerald Triangle growers? Kogan says he understands their plight and doesn’t want to take their business.

“I’ve faced open hostility from North Coast folks with what we’re doing here,” he admits. “But we’ve got multi-generation growers down here as well, and we’re doing what’s available to us.”

What’s available to northern growers, he adds, is appellations: identifying and marketing products with distinct geographical place names — a strategy employed by winemakers around the globe. (The California Growers Association is already pursuing this avenue.)

Emerald Triangle growers could also distinguish their product as sun-grown buds, distinct from anything cultivated under a roof in Monterey County.

But there’s another hitch: flower power may be on the decline. To appeal to new consumers, Kogan says the industry is moving away from smokable bud toward salves and candies made with cannabis oil — a commodity in the making. That’s where much of Grupo Flor’s business lies. It remains to be seen if customers will continue to seek out Emerald Triangle flower over more versatile oil.

Can big pot and little pot coexist, as Kogan imagines? Alicia Rose consulted for the Napa Valley wine industry before she opened a virtual cannabis dispensary called HerbaBuena, which specializes in sun-grown, biodynamic cannabis from heritage Emerald County growers.

She sees an opportunity for branded “farm-to-table” cannabis that comes with a story – for example, flowers grown outdoors by organic farmers on a small family plot in an ocean-cooled valley in Mendocino County — as the best hope for Northern California’s cottage growers.

For the Napa Valley of pot to survive, in other words, it might have to learn and adopt the marketing lessons of the actual Napa Valley.

“It gives me a little glimmer of hope we’ll be able to stay above the fray,” she says. Her hesitation? Backwoods growers who have long operated under the radar lack a certain business savvy. After all, they’ve succeeded in large part thanks to their ability to lay low. And that doesn’t usually translate into Napa-like promotional and sales skills.

Casey O’Neill, however, may have the adaptive qualities to make it in California’s new cannabis economy. Over the decades, he has played many roles: black market grower, plant breeder, cannabis consumer, and felon (he spent two months in the Mendocino County jail for cultivation). Now he’s a tax-paying cannabis farmer and policy activist.

Through it all, he has argued for the value of cannabis as a medicine, and for the benefits of small-scale, environmentally sound cultivation. Today, laminated cultivation permits hang on posts at the entrance to his farm. He relishes the security, predictability, and peace of mind that comes from running an above-board business.

Serving on the board of directors for the California Growers Association, O’Neill has become a strong advocate for small-scale cannabis cultivation. Perhaps hedging his bets, he also recently accepted a position in business and policy development at Flow Kana, a cannabis distributor building a 85,000 square-foot “cannabis campus” in nearby Redwood Valley.

The facility, which also houses a retreat center, will process, test, and distribute co-branded cannabis from some 80 boutique Mendocino and Humboldt county growers, operations not unlike the O’Neills’ HappyDay Farms.

So far, Emerald County growers don’t consider the San Francisco–based Flow Kana a threat. Rather, it’s a lifeline that, if all goes well, will help them stay afloat. Casey and Amber trust that the co-op will help them reach “discerning customers” — people who will seek Mendocino County sun-grown weed the way wine drinkers seek biodynamic-certified Napa cabernet.

“The strength of the story is what we’re counting on to keep us in the game against bigger, more capitalized operations,” O’Neill says. “Grown in a greenhouse has only so much story to it.”

Produced in collaboration with the Food & Environment Reporting Network, a nonprofit, investigative news organization.