Bob Brown looks a caricature of an Australian senator: a bit disheveled in a rumpled gray suit, unfashionable glasses, and a goofy grin. But a little rumple goes a long way. In a career that has spanned three decades, Brown has brought new awareness of environmental and human rights into the Australian political process.

The former doctor became the director of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society in the 1970s, during a bruising and ultimately successful fight to stop the damming of the Franklin River. Imprisoned in 1983 after being arrested at a protest, Brown was elected to Tasmania’s Parliament on the day of his release.

Since then, Brown has served as a member of federal Parliament, and is now in his second term as a senator. He is the leader of the Australian Greens, which he helped found. Besides his environmental work, Brown, the first openly gay Australian Member of Parliament, has spearheaded human-rights initiatives in Australia and abroad. And he’s been a leading voice of opposition to the Iraq war: In 2003, Brown was one of only two Aussie parliamentarians to speak out during President Bush’s address to their body.

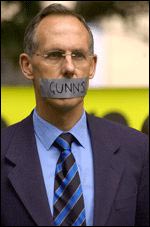

Grist met with Brown in San Francisco, where he was receiving an award from Rainforest Action Network, which is involved in a campaign against Gunns Limited, an Australian forest-products company seeking to build a pulp mill in Tasmania. The situation has been nasty — a lawsuit filed by Gunns against Brown and others has gone to the Australian supreme court, where it has become an important free speech case — but Brown, with his plummy Aussie voice and cheery energy, seems to relish a just fight.

It sounds like you’re in dire straits if you’re coming to a United States group to get help in an environmental struggle.

I do reckon. Ah, well … at least there’s Rainforest Action Network. It gives me a charge to visit here and catch up with the people involved in what’s got to be the alternative future for the planet.

Enough said.

Gunns is the world’s largest hardwood chipper, and it undertakes most of the old-growth forest logging in Tasmania. It chips trees into pieces not much bigger than a dollar piece and sends them to Japan. Tasmanians get about $10 to $12 (AUD) a ton for that. Gunns gets somewhere between $100 and $200 a ton just for putting the trees through a giant pencil sharpener. And the Japanese papermakers get about $1,200 a ton. So there’s a hundredfold markup. We grow the trees for 200 to 500 years, and within three months, the papermakers are making 99 percent of the profit. It’s a Third-World extractive process.

You’re in these forests all the time. Can you describe them?

Tasmania is the size of Ireland. It’s a mountainous island, and as a result, it’s got more rainfall and so more forests than the very dry continent of Australia. These forests include temperate rainforests but also the eucalypt forests — the tallest flowering trees in the world. The biggest are [320 feet tall], and some of them are over [65 feet] in girth.

The forests are full of wildlife: marsupials, bats, a lot of small kangaroo species, and a range of possums, and bird life, including the Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagle, which has a wingspan of [seven feet] and is one of the biggest birds of prey in the world. Its extinction is all but certain if these logging plans go ahead.

The forest is simply stunning — remnants of the wild world from which we all come. It’s why we put pictures of forest and wildlife on our walls, not chainsaws and bulldozers.

Do you remember a singular moment when you realized you had this connection with the forest and that it was threatened?

I remember as a youngster bringing a bunch of flowers out of the nearby woods to my mother and she gently remonstrated me and said, “They’re beautiful. I’ll put them in a vase. But they were more beautiful back on those trees.” I’ve never forgotten that moment of awakening.

A lot of the discourse in the forest debate in Australia is about jobs, even the Green Party’s Forest Transition Strategy. That reminds me of what’s gone on in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia in recent years. Do you see similarities?

Oh, absolutely. It is a clash between the stock-market, money-rules ethic of the right and the view of the left — that as human beings, we are custodians of this planet. As a Green, my goal is to put a smile on the face of the coming generations.

It’s a very positive, self-enhancing view to take into politics, but it makes the logging representatives very angry. They cannot understand that people would want to get into Parliament and advocate values that don’t convert directly into personal gain. For them it always raises the question, “What is motivating these people?”

Well, it’s the forest. Going to the forest restores me; it fires the boilers to sleep out for a night in the forest in Australia. It’s a nocturnal wildlife scene: it’s a hugely invigorating experience to hear the owls calling you.

The Green Party has a presence in countries all over the world. That hasn’t happened since the Communist Party had global influence in the 20th century.

Yeah, but it’s a very different setup. The Greens are a coming-together of like-minded political activists, in a common response to rampant materialism. Whether you’re in Buenos Aires or Beijing, there are people seeing exactly the same problem and having exactly the same response.

We’re fighting global corporate interests. They’re happy to globalize the economy but they’re not happy to globalize human rights and they’re not happy to globalize environmental protection. The Greens or some alternative are crucially important: it’s a way to get in there as the political arm of the activist and civil-rights movement.

To bring that home, the Australian Greens hosted the world’s first Global Greens Conference in Canberra in 2001, and established a charter that outlines the Greens’ philosophy. It was adopted by people from [more than 70] countries. The next global conference will be in Nairobi in 2008.

Your career includes a human-rights aspect that encompasses gay rights, prisoners’ rights, aboriginal rights, and so on. How does it all come together?

The overarching factor to me is if we can’t be kind to each other, we won’t be kind to the planet. Celebrating diversity in nature leads directly to celebrating diversity in human beings. Instead of being defensive or aggressive about difference, we should be celebrating it. You can’t divorce social justice from environmental problems — they’re interlocked.

Are there lessons that can be learned in the different struggles?

Well, firstly, international support is gold. One of the key things with the Franklin campaign was a group from the U.S. rafted down the river in 1980 and spoke out about it. It had an electrifying effect. It really helps.

And it’s our job to not just be a receptacle but to follow on. So I like to speak out about the logging disasters appearing in Papua New Guinea, in West Papua, and elsewhere in the Pacific. It’s the same with human rights, in Tibet and elsewhere.

You were doing that when you spoke out to George W. Bush in Parliament — in 2003 you were one of the few public voices questioning the war in Iraq.

When George Bush came to the joint house in Parliament, it was like the Lord himself had arrived back on Earth. You could hear a pin drop. It was an extraordinary crowd, frozen to their seats. It was an inappropriate reaction for our Parliament. We were elected there to stand up and speak on behalf of our electorate.

So it was the logical thing to do at the time, but if I hadn’t been around as long as I had, I wouldn’t have done it. In fact, I said to my fellow Greens the day before, “This is going to be very frightening and if we don’t do it, don’t feel bad about it. All I know is if we don’t attempt to do it — if George Bush comes and speaks to our Parliament and we sit there like automatons and say nothing — we will feel bad about it.”

Do you think that idea applies more broadly?

Oh, yeah. The trick is to just step one step — not a football field, but one step — outside your comfort zone. You can do it with confidence.

And your experience in doing that has been successful.

Yeah, and it’s had an effect. George Bush was asked to address the joint Parliament in Ottawa and in London and turned them both down because of the threat of even bigger numbers of politicians getting up.

When we did it, there was an enormous and angry response. All sorts of right-wing commentators were going to punch my face in and bust us up and so on. But now when I go around Australia, people keep coming up and saying, “Thank goodness you stood up on George Bush; you stood up for me.”

Do you see your forest work as a similar duty?

Logging mania in Tasmania.

Photo: iStockphoto

Now, this needs to be said: although most Tasmanians want the forest saved, both political parties want the pulp mill, both at state level and national level. So left to their own devices, we’ll get rolled over. Bring in RAN, bring in international common sense on what’s happening in Tasmania, and the odds shift. And that brings us a feeling of strength — we’re not isolated anymore.

Gunns is trying desperately to get investment to build this $1 billion (AUD) pulp mill. And the question is which bank, which commercial group are they going to get to take it on? A lot of investment organizations have had a look and walked out the door. Sooner or later, they have to find somebody who’s going to invest, and when that happens, they’ll feel more confident about going ahead.

It does sound pretty rapacious, right down to this poison carrot thing. Have you seen that happen?

Oh, yeah, they drive along in their truck and throw [small piles of] carrots off the back, which get eaten by the marsupials. They condition the animals, then come along a week later with carrots laced with poison. In the last year there are statistics, 97,000 or 98,000 [animals] were poisoned, it’s estimated. Because the animals are little anti-profit machines. But the issue became huge in the last national election, so they’ve stopped that in public forests — but not in private forests.

Last time I interviewed an Australian doctor it was Helen Caldicott. She draws a lot of her activist inspiration from her medical work.

Yeah. I do, too. It’s important for activists that they be kind to themselves. People have to not panic, not feel it’s too late, and to take their time.

You’ve got a choice: you can be optimistic or pessimistic. I spent a little while depressed when I was young. Well, get depressed — look at the world and get depressed — then get over it. Put that on the shelf.

It’s important we campaign strongly, but it’s important we look after ourselves and those around us while we’re doing it. I often quote Emma Goldman: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” It’s a very good message.